By Marc Choyt

Photo by Josh Humbert

The land we bought was at the southwestern edge of the Rockies, where the plains meet the mesa and mountains. Rain fell in splashes and the winds had a wild fierceness. Toward the west were peaks higher than 10,000 ft; eastward, 1000 miles of flat grasslands.

A river snaked through—though, outside the desert southwest, the channel, which served as a lifeline for the tiny ranching community, might only be considered a creek by many. Over the decades, mainly because of the impact of cattle that lived on the land, the river’s gently sloping banks had transformed into 10- to 20-foot deep cuts.

A few miles outside our valley, the river dried out—and with it, any potential for the great diversity of flora and fauna that characterized waterways in our bioregion.

The year was 2005, and the internationally launched ‘No Dirty Gold’ campaign was gaining traction. My design company, Reflective Jewelry, had been in business 10 years and had sold to hundreds of stores.

While assessing our situation, we thought about sustainability, which Merriam-Webster defines as:

relating to or being a method of harvesting or using a resource so that the resource is not depleted or permanently damaged

Sustaining the river, however, with its eroded banking, would not catalyze restorative ecology; and, as for our business, the mining required to supply our company was certainly not sustainable—but our business was profitable.

As we budgeted funds to repair the river in our slice of paradise, the connection between local action and global impact became all too clear: mined metal, the gold we use to make our jewellery, could be destroying the ecology of another river across the world.

Sustainable jewellery

Back then, when showing at the JCK Designer Pavilion, there were few options available for companies (like mine) interested in creating wedding rings in which sourcing aligned with symbolism. Simply put, eco-friendly, fair trade jewellery was not in fashion.

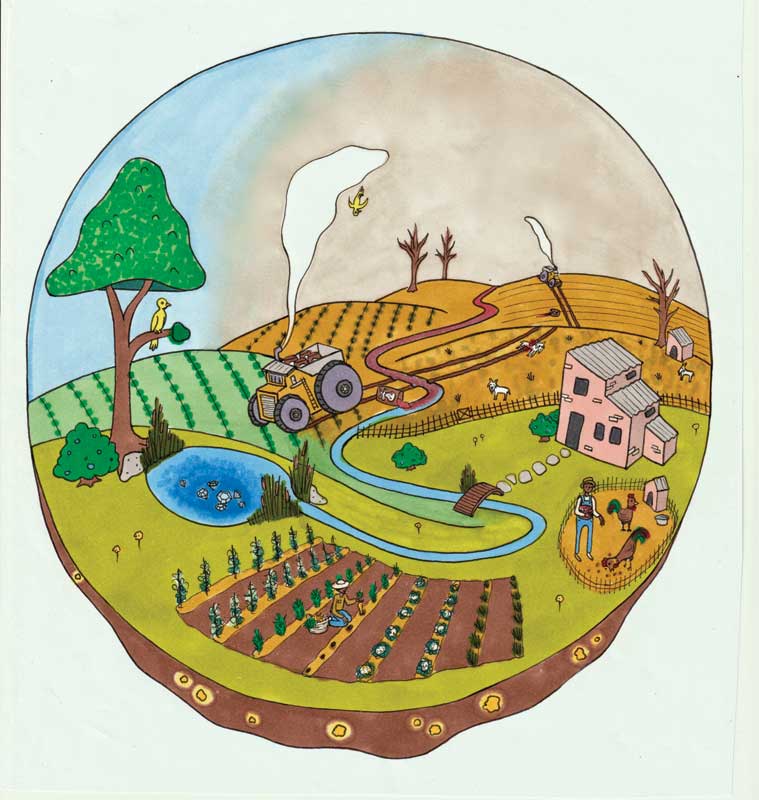

Illustration by Allyssa Barstow (alyssathefriend.com)/ courtesy Marc Choyt Reflective Jewelry

These days, however, we’re in a different universe; indeed, concerns surrounding the environment and ethically sourced materials define millennial consumers. Studies have shown 78 per cent of those aged 18-24 (a.k.a. Gen Zers) are willing to spend more on a product or service if it is more ethical than its less expensive counterpart.

To that end, jewellers commonly use terms such as ‘sustainable,’ ‘eco-friendly,’ ‘ethical,’ and ‘responsible’ in their marketing.

In North America, recycled precious metals, an initiative pioneered by Hoover and Strong in 2007, remain the cornerstone of the sustainable jewellery pitch. Back then, a jeweller could simply start using recycled gold/silver and become an ethical sourcing pioneer. Signing the ‘No Dirty Gold’ pledge also satisfied some non-governmental organization (NGO) watchdogs, which were often considered hostile entities by trade leaders.

In the years that followed, recycled metals became a strong market narrative, particularly fuelled by Brilliant Earth. These days, Stuller, Rio Grande, and many retailers anchor sustainability claims on recycled product. (See: “The Ultimate Brilliant Earth Review: Bullsh*T, Or Ethical Jewelry Leaders?”)

Diamonds, too, have joined the ‘sustainability parade.’ Recycled diamonds are increasingly popular, with customers appreciating they are not newly mined (particularly melee, which is hard to acquire in Canadian-mined sourcing).

Of course, the big sustainability disrupter is lab-grown diamonds. The ever-increasing market share of these synthetic stones is fuelled by a lower price point and ‘conflict free’ consumer-facing marketing. And, while whether mined diamonds are more sustainable than their lab-grown counterparts is debated in the trade, companies such as San Francisco’s Diamond Foundry do offer an additional eco-friendly angle, as the company is certified carbon neutral.

Overall, while these initiatives have successfully driven marketing to consumers who are concerned about sustainable practices, this success has not changed the mining practices, which still underpin the supply chain.

The big picture

Illustration by Allyssa Barstow (alyssathefriend.com) /courtesy Marc Choyt Reflective Jewelry

Currently, mining for product used to make jewellery continues just as it always has, with large-scale mines supplying 80 per cent of gold and diamonds and extracting resources as fast as possible. The commodity market hides externalities—that is, the broader impact to cultures and the environment.

The balance of source material comes from small scale mining. The 100 million people who dig with shovels, perhaps moving a ton of dirt a day, are working to feed themselves and their families. Their existence is characterized by extreme poverty and exploitation—and, in the case of gold, environmental toxification.

It would be one thing if using recycled gold or diamonds (even lab-grown diamonds) impacted large- or small-scale mining practices, but these materials are commodities. For large-scale operations, it’s fundamentally all about the economics of a particular mining site and shareholder value; for small-scale, it’s often about survival the politics of putting bread on the table.

Indeed, if we conduct a careful analysis, it’s apparent the sustainability argument in context to gold and diamonds has a very thin vermeil.

After all, the recycled diamond I sell might have been mined by De Beers in the 1980s—a time when millions were killed in wars, funded by these precious stones. Suppose you were the guy in Sierra Leone who had his hand hacked off 30 years—how would you feel about the claim of an eco-friendly, conflict-free, recycled diamond that had, in fact, resulted in your family being killed?

And, regarding lab-grown diamonds, I find it incredibly ironic that Leonardo DiCaprio, who starred in Blood Diamond, supports these synthetic stones rather than throwing his support behind the impacted communities depicted in the film. He, too, ignores the atrocities funded by diamonds, and the extreme poverty of the 20 million small-scale diamond miners, making a few dollars a day.

A ‘certified’ 100 per cent, eco-friendly, recycled gold ring may have come from a small-scale miner who burned off the mercury gold amalgam in his frying pan before cooking his plantains. Alternatively, a jeweller might proudly sell a recycled gold ring to a millennial couple, seeking to create a more beautiful world for their future family, not knowing the material used was originally mined by Imperial Metals’ Mount Polley Mine—a site home to one of the worst environmental disasters in Canadian history.

Gold is just a soft rock

Bev Sellars was chief of the Xat’sull (Soda Creek) First Nation in Williams Lake, B.C., before the Mount Polley tailings spill in 2014.

Photo courtesy Bev Sellars with permission from the author

Now, nearly six years later, the moose her family hunts often have spots on their livers. The water she once drank is no longer safe. The salmon runs in Fraser River, a place where she loved to fish as a young girl in the ‘70s, lack vitality. Plus, 2000 legacy mines in B.C. continue to ravage the ecosystem.

Chief Sellars is also an attorney and an expert on mining issues. She served as chair of First Nations Women Advocating Responsible Mining (FNWARM). We spoke on April 3, discussing mining, sustainability, and Truth and Reconciliation in Canada. (Read the author’s complete interview with Chief Sellars online here.)

“If you want to reconcile with Indigenous people, first reconcile with Mother Earth,” she said. “Our community’s economy comes from the land and the water.”

“Could mining ever be justified in developing countries where it was the only means of survival?” I asked.

“Poverty is often used against people by mining companies,” she answered.

I thought of stories I had followed, such as the blockade at De Beers’ Victor Mine in northern Ontario, staged in 2009 by members of the Attawapiskat First Nation, and how Impact Benefit agreements often fragmented traditional cultural guardians and the pro-development tribal governments. (See “Attawapiskat and De Beers Victor Mine Blockades.”)

In my consultations with the Sierra Fund in California, which focuses on the mercury from legacy mining in California Natives, one Native spokesperson told me gold was, ‘coyote p**s.’ Stories of members of the 49ers tribe bashing babies’ heads against rocks were so present, they might as well have happened last week.

“The dilemma,” I said to Chief Sellars, “is small-scale mining is the largest contributor of global mercury contamination. For [the miners], it’s about feeding their families.”

“If mining can be done in a manner in which the environment isn’t harmed in a big way and only if there is an absolute need,” she said.

She went on to explain the 94 ‘calls to action’ posed by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, which was created to help repair harm caused by residential schools, can, in actuality, all be reduced to one.

“It’s all about the water. If the water is clean in a natural state, then the environment will be healthy.”

Regenerative models

Photo courtesy Alan Frampton/MacDesa

Personally, I have lived with a critical question for 15 years: how do I restore my river without destroying a river somewhere else? Now, more than ever, this is imperative.

We are in the midst of the sixth great extinction, with 30,000 species dying every year. In the coming decades, temperatures could rise two degrees and sea levels could climb another two feet. What’s more, Canada’s rate of warming, which is higher than most other global regions, threatens the survival of some Inuit communities.

The solution is to stop advocating for sustainability and start focusing on reciprocity—that is, a supply chain that has a fair and equitable exchange with communities and ecosystems.

Conduct all elements of our business in a manner that would increase cultural and biological diversity, laying the ground for the needs of future generations.

There are already models for such a change.

Currently, there is only one Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States (me)—but suppose there were thousands, spread across North America? Global mercury pollution and poverty would significantly reduce and millions of small-scale miners would be uplifted out of poverty.

Back in 2008, the Tiffany & Co. Foundation funded a fair trade diamond study, conducted by TransFair USA. Even back then, it was abundantly clear there was great market potential for such a product, and the Diamond Development Initiative (DDI) was founded with that clear intention. (See “Death of the Fair Trade Diamond.”)

Remarkably, for all the positive narrative this initiative has garnered over the past 12 years, not one diamond branded as DDI small-scale miners-sourced has reached the market.

If I could offer my many customers who are concerned about blood diamonds a redemptive third party-certified fair trade diamond from small-scale miners in Africa, I would sell them all day long. However, that diamond is not likely to be coming any time soon.

A fair trade diamond, with a powerful redemptive story, has the potential to disrupt the diamond industry. The DDI supply chain is distributed by De Beers, and the dominant ethical narrative theme for African diamonds is beneficiation coming from large-scale operations.

Meanwhile, regarding coloured gemstones, fair trade standards developed and pioneered by Columbia Gem House offer a good model. Moyo Gemstones directly support the work of women miners in Tanzania. Likewise, Kamoka Pearls are grown in a Tahiti in a manner that actually improves marine environment. Rubyfair, a project in Tanzania, has a policy, “to leave the claim in no worse and preferably better state than when operations began,” which could be duplicated in other areas.

All these initiatives support local economies, reduce poverty, and are less impactful on the environment than as compared to conventional practices.

The river

Back at the land we bought—at the southwestern edge of the Rockies, where the plains meet the mesa and mountains—I brought a community of friends together with shovels. I hired a bulldozer, which, in a day, took the banks of the river down to a gentle slope. We planted hundreds of cottonwood and willow, and spread wild grass seed while dark clouds gathered above the mountains. A flash rain could easily wash away our work.

Photo courtesy Alan Frampton/MacDesa

Our river was surrounded by a million acres of wild lands; over the years that followed, the willows, grasses, and cottonwoods established along the bank. Beavers moved in, creating ponds for trout and nesting water fowl. During a severe drought, when most of the river dried out, our little section became a seed for the entire ecosystem when the waters finally came back.

Nonetheless, the river of our current ethical responsible supply chain remains a kind of nefarious greenwashing—one which to impact current mining projects, ignores historical atrocities and undermines the potential for real change.

These neocolonial practices, fed by the same commodity chains that created Mount Polley, are, indeed, obscured by the sustainability trap.

Likewise, extraordinary market alternatives to the poverty and mercury toxicity associated with small-scale mining, such as fairtrade/fairmined gold, are eclipsed by the recycled gold sustainability trap.

Nor does the sustainability address the millions killed in blood diamond wars, or the 20,000 killed in the Bougainville Massacre at a Papua New Guinea mine owned by Rio Tinto—a company certified as a ‘responsible source’ by the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC).

Only through the creation of regenerative economies—“based upon reflective, responsive, reciprocal relationships of interdependence between human communities and the living world upon which we depend”—can we create a hopeful future our hearts know is possible.

The current generation of buyers is more concerned about global warming and mass extinction than your bottom line. They want to align their values and their economic decisions. Further, they are savvy and it is risky to mislead them.

From my position as a pioneer of ethical jewellery practices from the beginning of this movement, I have watched this subversion thinking, noting that all movements start small. You can be part of it.

Among many things that can be learned from the COVID-19 crisis, great change can happen quickly under the right conditions.

Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry, a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds, is available online, at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifesto or by email at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

For more features by Marc Choyt, check out “A dream deferred: Ethical gold in North America” and “What makes ethical jewellery ethical?“

Tremendous article highlighting the extensive greenwashing, intentional or not in our industry.

The last several years it has become increasing challenging to source sustainably, and to internalize the environmental and social costs into our jewelry. And yet, the ‘sustainability movement’ in jewelry has never been so featured in our marketing and trade organization. This disconnect is palpable.

This is an absolutely good website! It is easy to navigate and follow!