Mixing marriage, family, and business: “Do I need a pre-nup?”

By Danielle Walsh

Getting engaged, planning a wedding, and exchanging vows are all momentous occasions in an individual’s life. Often, those planning a wedding focus on the ring(s), the venue, and the flowers; however, if you’re a business owner or a potential owner (i.e. successor), careful consideration must also be given to developing a plan that will reduce financial risk to the business in the case of divorce.

While we all like to think, “That won’t be me,” statistics on divorce tell a different story. Indeed, these numbers indicate that taking appropriate precautions before walking down the aisle is simply good sense, as this pre-preparation can save a family-run business from a world of grief.

Many business owners don’t realize the financial consequences of divorce and the effect it might have on them and their operations. As such, the impact of this life event is often much more significant than anticipated—what’s more, when you’re in business with other people (including family members), the consequences impact all owners; not just the one who’s getting divorced.

Brothers divided

In my years working as a family business advisor, I’ve witnessed many difficult situations where the outcome might have been very different if the potential of a marital separation had been anticipated before it occurred.

Consider this scenario:

There were three brothers who, for 18 years, jointly owned and operated a business inherited from their grandparents. All of the brothers were married and had been for more than 20 years.

Then, seemingly out of the blue, one brother’s spouse sought a divorce. None of the siblings had pre-nuptial or nuptial agreements. The split ended up in court, where the estranged wife’s lawyer claimed the land upon which the business operated was worth at least three times the value assigned by the business’s accountant for the divorce settlement. This claim was based on the land being sold for multi-use development rather than how it was currently used. The estranged spouse had a developer provide an offer on part of the land that was greater than the amount assigned to the entire business. This resulted in large parts of the land being sold to a developer, which funded the divorce settlement and legal fees. The two brothers and their parents blamed the brother getting divorced for tearing apart the business and the family unit. Thus, at a time when the brother getting a divorce needed support from his family, he was blamed.

This situation wasn’t the fault of the brother getting divorced; the siblings should have had a domestic agreement, such as a marriage contract (or pre-nuptial agreement) in place, and their parents and advisors should have ensured all business partners were aware of the terms. Instead, a situation developed whereby the family was so devastated that, rather than offer support to the brother getting divorced, they took their emotions out on him. In reality, any of the three brothers could have been the one getting a divorce.

Unfortunately, this account is simply one of many cautionary tales relating to family businesses and the impact of divorce. In these operations, divorce always hits close to home; the business is the vehicle that provides members of the family an opportunity to be their own boss and build a legacy they can pass on to future generations.

Pen to paper

All family businesses should have a comprehensive succession plan in place that outlines the operation’s basic guiding principles, as well as rules that allow family members to make objective decisions relating to the family that are best for the business.

Most of my family business clients endorse a rule stating all owners must have a company lawyer-approved domestic contract (i.e. a marriage contract or co-habitation agreement) in place with their spouse in order to be an owner of the business. This is also stipulated in the shareholders agreement.

The domestic contract needs to stipulate the family business is excluded from any division or equalization of property that will happen in the event of a separation. As a note, this requirement is typically not insisted upon for members of the older generation (who, sometimes, have been running the business for well over 30 years and have been married for more than that still); however, this should be a requirement to make it into ownership for the next generation or any future owner. Further, if an older-generation owner does divorce, they would be required to obtain a marriage contract if they remarried.

Regarding the case of the three brothers detailed above, had their parents and/or advisors ensured this kind of domestic contract was in place for each sibling, it would have protected the family business and saved the brothers’ relationship.

Beyond family

Likewise, failing to solidify a marriage contract can also lead to significant issues for non-family businesses.

Consider this scenario:

Michelle and David, both married to their respective spouses, had co-owned a business for 10 years. Their operation had finally hit a comfortable point where the owners were able to focus on implementing a plan for strategic growth.

David, without warning, announced to Michelle he and his wife had begun the process of divorce. Suddenly, Michelle found herself spending considerable time trying to convince David and his wife to work things out, as she realized neither she nor David had marriage contracts in place. If this divorce went through, the partners would owe David’s estranged wife 25 per cent of the value of the business, and, given they were hoping to implement a growth strategy, they would not have any cash to spare. Michelle recognized they would need to change their three- to five-year plan significantly to pay David’s ex-wife what she was owed, since including her as a 25 per cent owner was not an option.

Michelle became engrossed with the impact the potential divorce would have and dedicated her time to figuring out how the business would survive. Meanwhile, David was distracted by his personal loss and focused on ensuring his children were well taken care of. Both Michelle and David lost sight of the day-to-day operations, which had a negative impact on the business, as well as their employees and customers.

Each province has specific legislation that sets out what happens to property (e.g. houses, investments, businesses, etc.) if a couple splits up; however, many provinces require that property accumulated during the marriage be equalized in the event of a separation.

In the absence of a domestic contract stating otherwise, in provinces that equalize matrimonial property, each person’s net family property is calculated as of the day they separate—assets, less debts, and excluding any exceptions such as inheritances or gifts. This then gets equalized by one person paying the other so both leave the marriage with the same value.

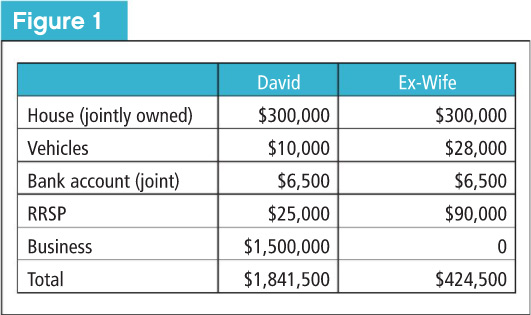

If we take a very simplified example for David and his ex-wife and look at their assets on the day of separation, we see their jointly owned house value ($600,000) is split equally, as is the value in their joint bank account; they each have the value for their respective cars and RRSPs.

David would need to get a business valuation, which can be a lengthy and expensive endeavour. Let’s assume the business is worth $3 million; therefore, his 50 per cent share is $1.5 million. (See Figure 1.)

David would need to get a business valuation, which can be a lengthy and expensive endeavour. Let’s assume the business is worth $3 million; therefore, his 50 per cent share is $1.5 million. (See Figure 1.)

In this example, David’s net family property is $1,841,500 and his ex-wife’s is $424,500. The difference between the two ($1,417,000) will need to be equalized—meaning, David owes his ex-wife $708,500. David could give her his stakes in the house and the joint account, as well as his RRSPs, but he will still owe her $377,000—and these funds will likely have to come from the business.

Michelle will feel the impact of David’s divorce. Their business is going to have to change its plans to compensate David’s ex-wife because David did not have enough other assets to do so on his own. The partners will likely need to pay this over time in order to keep the business afloat. Even though David’s divorce has nothing to do with Michelle, she has a big role to play and is impacted in a significant way. All of this to say, without a domestic contract, divorce can easily derail a business if it is not equipped to survive such an event.

In this case, had there been a marriage contract in place that excluded the value of the business from the net family property in the case of divorce, David’s net family property would be $341,500. Unless some of the wife’s property was also excluded in the marriage contract, his ex-wife would actually owe him $41,500—and, more importantly, the business would remain untouched.

Having a domestic contract can assist families with prearranged agreements so they know what to expect in the event the marriage breaks down. This can safeguard a jointly owned business and provide all owners with piece of mind.

Prevention

Domestic contracts (i.e. marriage contracts, co-habitation agreements) protect businesses, and more importantly, ensure everyone involved has a clear understanding of what will happen if a separation occurs. The contents can vary, but these contracts typically include clauses about the division of property and spousal support in the event of a separation. Specifically for businesses, this value can be excluded from the equalization of property, which protects the operation and lessens personal conflict among family and business partners.

Of course, having a conversation about needing a marriage contract or pre-nuptial agreement can be difficult; however, if those who own the business agree to undisputable rules and principles, this paperwork becomes just one more method of reducing risk and protecting the business. As such, if all owners can agree marriage contracts are required for all current and future owners, introducing this conversation with a spouse is no longer personal; it is simply an objective item that is required to protect the business and all of the hard work that it takes to run it.

Consider it this way: most business owners have some form of life insurance and disability insurance. No one likes to think they’re going to die or become disabled, but they have insurance to protect their business and families in case it happens. The same should be said for domestic contracts—they’re simply another form of insurance or prevention. Starting, running, and growing a business is difficult enough without having to deal with the financial repercussions of a divorce. Indeed, the old adage ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’ holds very true when it comes to domestic contracts.

Seeking advice

When drafting any domestic contract, it’s very important to get the advice of a lawyer. What’s more, this paperwork takes time to put together—so, once you’re engaged, it’s time to call the lawyer!

It’s also important these contracts are signed far enough in advance of the marriage (with adequate time to negotiate terms) so the non-business owner doesn’t make allegations of duress down the road. Both parties are strongly encouraged to have independent legal advice; the strength of the contract depends on both parties making full disclosure of their assets and debts. It should also be noted no two marriage contracts are the same.

Further, just because a contract states a spouse cannot put a claim (financial or otherwise) on the company’s shares or their value, this doesn’t mean the contract won’t account for another way of compensating the non-business owning spouse. These conversations need to be had in order to be able develop a contract that works for both parties.

And, hey, if you’re never going to get divorced, then you won’t need to use this contract—but you’ll be happy if a business partner who does get divorced has one!

Danielle Walsh is founder of Walsh Family Business Advisory Services, a consulting company specializing in helping family-owned and operated businesses navigate management and ownership succession. She is a certified public accountant (CPA), chartered accountant (CA), and holds certificates in family business advising and family wealth advising from the Family Firm Institute (FFI). Walsh developed her philosophy and desire to help family businesses from her father, Grant Walsh, who has worked as a family business practitioner for the last 25 years. She and her father recently published a book titled A Practical Guide to Family Business Succession Planning: The Advice You Won’t Get from Accountants and Lawyers. Walsh also currently teaches the first family business course offered at the undergraduate level at Carleton University in Ottawa. She can be reached at danielle@walshfbas.com.

Danielle Walsh is founder of Walsh Family Business Advisory Services, a consulting company specializing in helping family-owned and operated businesses navigate management and ownership succession. She is a certified public accountant (CPA), chartered accountant (CA), and holds certificates in family business advising and family wealth advising from the Family Firm Institute (FFI). Walsh developed her philosophy and desire to help family businesses from her father, Grant Walsh, who has worked as a family business practitioner for the last 25 years. She and her father recently published a book titled A Practical Guide to Family Business Succession Planning: The Advice You Won’t Get from Accountants and Lawyers. Walsh also currently teaches the first family business course offered at the undergraduate level at Carleton University in Ottawa. She can be reached at danielle@walshfbas.com.

This article was reviewed by Kathleen Wright, a lawyer at Mann Lawyers in Ottawa, who practices in family law, wills, and estates. She can be reached via email at kate.wright@mannlawyers.com.