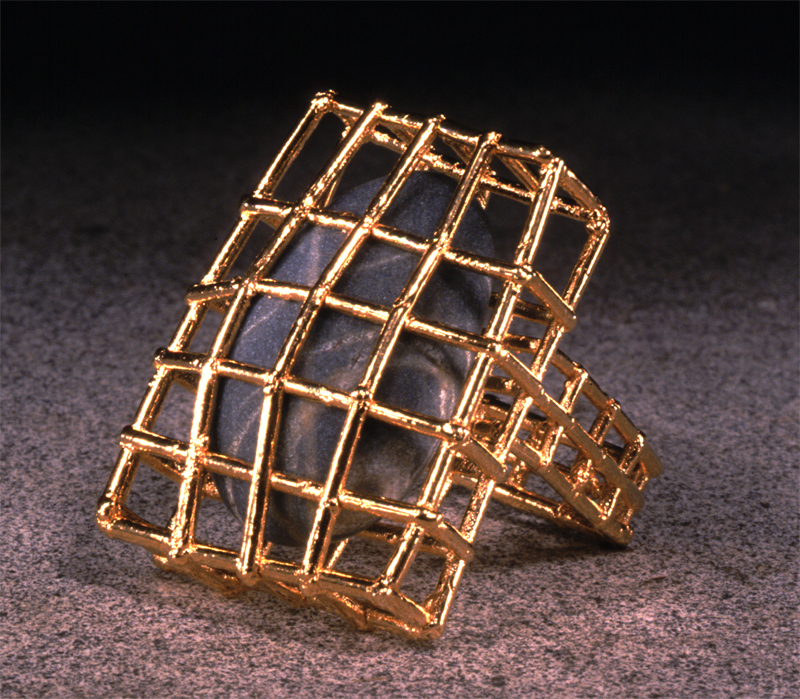

Sneak peek: ‘Caged refinement’ by Charles Lewton-Brain

Photo © Charles Lewton-Brain

Electroplating is the application of a very thin layer of metal onto a different metal using electrochemistry. The process uses a solution (called a “bath” when electroplating), which is a mixture of metallic salts dissolved in an acidic or a basic solution.

For author, educator, and master goldsmith Charles Lewton-Brain, both electroplating and electroforming have been instrumental in refining his voice and style within the world of jewellery fabrication. Specifically, he uses grids of fusion-welded stainless-steel wire to create structures, which are then electroformed.

In the upcoming February issue of Jewellery Business, Lewton-Brain offers a behind-the-scenes look at his use of this process and the ways in which it has brought further life to his work.

Check out the excerpt below:

Electroplating and electroforming are incredibly interesting; they build metal layers atom by atom, the smallest particle deposited onto the surface, as part of a process called ionic deposition.

There is no finer way of making a mould. Indeed, this perfect surface reproduction has long been in practice. In 1830 or so, the process was used to take moulds of clay busts of Napoleon. These were then used to cast porcelain and, ultimately, to create fired ceramic busts with the exact detail of the original.

The created surface is so perfect that this is how vinyl records are made: A wax disc is incised with vibrations caused by sound, which is then electroformed and the negative of the incised wax disc is used to stamp the vinyl record. This use of electroforming was also previously used for plastic injection moulds (now supplanted by computer-aided design/ manufacturing [CAD/CAM] milled moulds).

Many makers ignore this exact surface reproduction side of things and instead use it, as I do, for growing metal onto things, as well as controlling the quality and nature of the surface by chemical additions to the electroforming baths. In my work, I deliberately use the roughness of crude growth to create texture.

When creating pieces such as these, I sometimes start with a drawing. I begin with a gemstone, then design responding to it, building around the stone using 0.5-mm stainless-steel wire, which is welded using an orthodontic fusion welder.

I think of it like drawing using thin metal wire: I can join the wire instantly, bend it with pliers, and intentionally weaken spots with the welder to make a bend point. When a piece is complete (which can include having trapped gems into place in the structure), it is immersed in an antique-style copper acid plating solution. The copper grows slowly—the slower it grows, the smoother the surface. This means a piece can take anywhere from three days to a week or so to grow. During this time, I control where it grows and how by repositioning the anode(s) (metal feed) and the cathode (the object) relative to each other often.

To read the rest of Lewton-Brain’s article, be sure to check out the February issue!