Gemstone depth: Cutting it close and critical

By Lauriane Lognay

Photos courtesy Rippana, Inc.

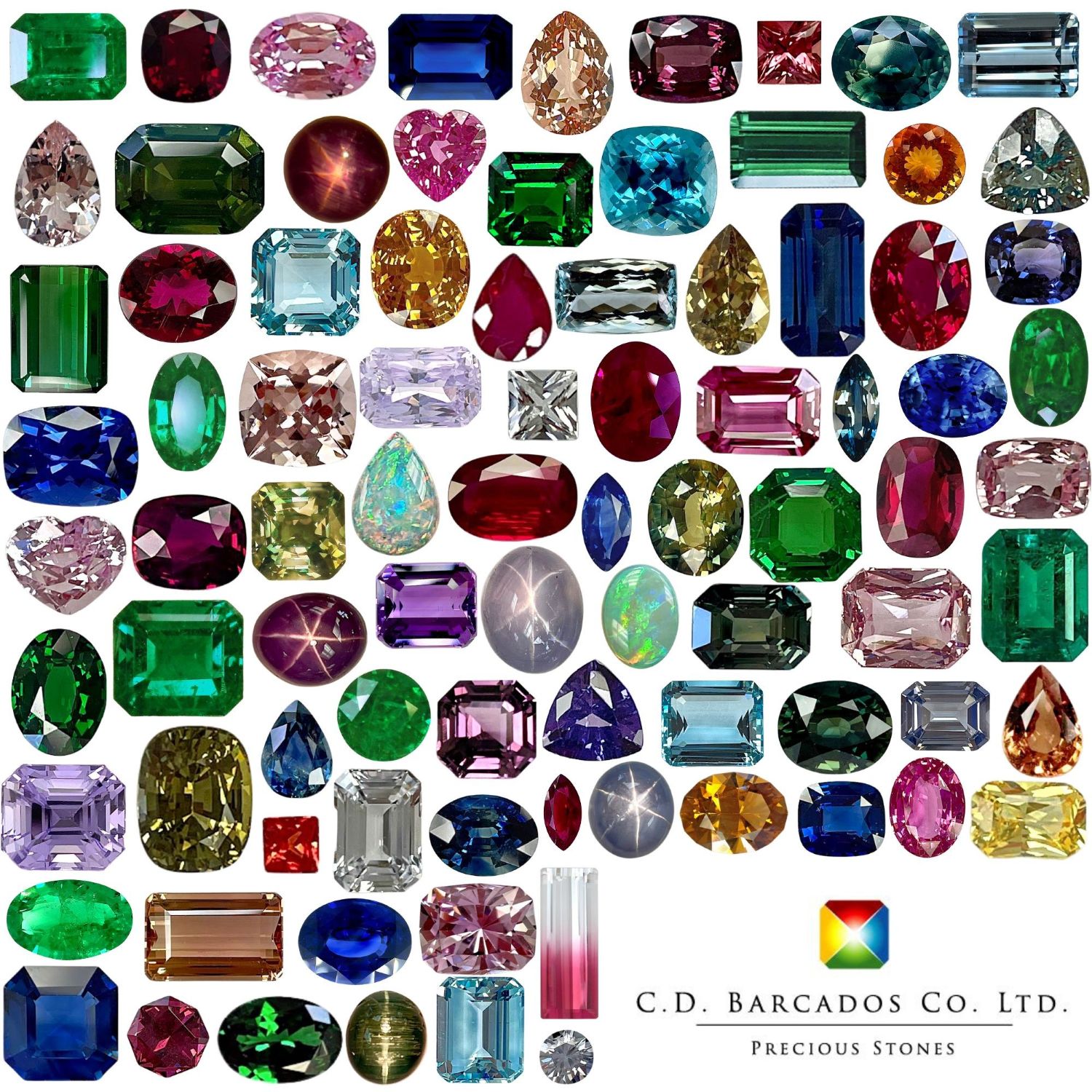

When it comes to lapidary work, this gemmologist has explored a myriad of facets in this column. Indeed, as we have seen, time and time again, the subject is seemingly endless, and knowledge is just within our reach. Nonetheless, common misconceptions seem to remain surrounding the depth of gemstones and the ways in which they are cut.

Do you often wonder why coloured gemstones all have different depths? Do your clients ever ask why, exactly, a particular gem is so shallow, and you find yourself unsure of how to answer?

What follows are a few explanations to help clear up possible misconceptions and, importantly, help make a sale!

Does depth matter?

Gemstone cutting is not only an art form, but also a scientific study. A poorly cut gem can lead to multiple consequences, particularly in the pavilion area, including fish-eye reflections, dead zones, windows, an asymmetrical appearance, and so forth.

Any cutter worth their weight in salt will study and learn about critical angle. This is, in a sense, the shallowest angle you can cut a gemstone to allow light to be reflected back at you (that’s right, a gemstone doesn’t shine—it reflects!).

Going under the critical angle when cutting causes a window in the stone. If you play a bit and add a few degrees to the angle while cutting, you can get the perfect refraction inside and the best reflection of the light. Of course, if you add too many degrees to your critical angle, you run the risk of dead zones (i.e. dark spots in the gem where no light gets reflected back). This is why understanding a gem’s refractive index is so important.

This aspect has been perfected in the diamond cutting industry and is why round brilliant-cut diamonds with the same diameter will have similar depths. While the coloured gemstone world has not yet established such a standard, professional lapidaries try their best to cut their gems with the perfect angles.

Right: On the market, this citrine would be considered to have a good cut. Depending on the angle, the small window disappears.

Why is my stone so shallow/deep?

I have often had clients ask questions, such as, “Why is this gem so shallow, but this other one is so deep?” or “Why aren’t all gemstones the same calibrated depth?” or “Why would two emeralds of the same diameter have different depth and pavilions?”

When it comes to gemstone depth, variations can be attributed to several factors, including:

- Cutter or customer’s choice

- Rough weight saving/not enough rough

- Critical angle

- Jewellery specifics

- Repair work

Cutter or customer’s choice

A cutter can decide on any design they wish for their stones. Esthetics sometimes triumph over potential weight retention, as can a lapidary artist’s desire to test a certain type of cut (even if the rough is another shape).

For example, an artist might decide to cut what we call a “bluff stone” (i.e. a gem that has a big diameter but is shallow and light) instead of multiple smaller stones with a normal depth to them. Likewise, the portrait cut is a situation where a cutter aims for the biggest window possible for their stone. It can also be because of the inclusions present in the stone—depending on where the inclusions are and how avoidable they are, they can ultimately determine the depth of a stone.

An opaque gem is another good example of “dealer’s choice” for optimal cutting. In these cases, there is no specific angle to follow, as no light can get reflected inside the stone, and the customer or cutter can decide what they will do with it.

Rough weight saving

Sometimes the only intent behind a cut is to lose as little rough as possible. In these cases, critical angle cannot be achieved. Instead, the best bet is to cut the stone as large and as deep as possible and allow it to be sold based primarily on its weight. This often happens with medium- to lower-quality corundum: These gems are sold at a lower price per carat, but the buyer gets a fat stone and ends up paying more for it.

Weight saving also comes in to play when a cutter is working with a rough that’s a bit on the thin side. In most of these cases, the only way to achieve the price desired is to cut the gemstone with a small window. In the end, though, the cutter must decide if he or she wants to try faceting a bigger stone with less-than-perfect proportions, or a smaller gem with ideal proportions. This will largely depend on the price that was paid for the rough and the price the gem can be sold for once it is cut.

A cutter may also encounter situations where the colour zone in a stone was not well placed. You will often see sapphires on the side almost colourless, if not for a splash of blue at the bottom of the pavilion. When the rough does not have a uniform colour and/or if the distribution of colour is not good, the lapidary artist uses their talents to place the spot of colour in a place where it will be reflected everywhere in the stone, making it look entirely blue. Most often, this is at bottom of the pavilion.

Critical angle

Though it may go without saying, I cannot stress this enough: Critical angle is crucial for a good cut! That said, depending on the type of stone, one will see different depths.

Cutting with the critical angle in mind helps lapidaries understand where and when they should stop their work, as well as what parts of a gem can be cut to allow for the best result. Light should be reflected on the inside facets of the pavilion, bounce around a little, and then come back toward the crown/table.

Typically, a spinel will be cut with a deeper pavilion than a diamond. Quartz, beryl, zircon, and topaz are other stones often found with a deep belly, as these tend to be windowed or dark otherwise.

Moissanite has a low critical angle and, as such, is a stone that can be cut shallowly enough without getting a window (however, just because this can be done, that does not mean this is necessarily the best angle to cut it at).

Jewellery specifics

Sometimes a gem has to be cut to fit into a piece of jewellery. In these scenarios, the cutter must respect the dimensions asked, no matter the type of gemstone.

This obligation can sometimes result in an asymmetrical or sub-par cut. The space in the setting might be too cramped and the prongs too short, so the lapidary artist has no choice but to cut a shallow stone to fit inside. Commercial-quality jewellery will often feature shallow stones to minimize on fabrication costs. These results are obvious to the trained eye—windows, windows everywhere!

Repair work

When it comes to repairs, a lapidary artist’s hands are largely tied. A client may come in with a ring, for example, that is missing its original stone. The lost gem was specially cut for the ring and now a new stone is needed to fit into the space.

As mentioned, most commercial-quality jewellery has gems to match—which typically means the stone originally set in one of these pieces did not have the best cut. As such, the lapidary artist doing the repair doesn’t have much wiggle room (though most cut miracles when they can).

Strength in knowledge

Understanding the importance of a well-cut gemstone and why, exactly, gems’ depths differ can go a long way in helping a jewellery retailer explain concepts to their clients. Knowledge is power—after all, most customers are after more than jewellery; they also want a story to go with their purchase, including interesting trivia and a sprinkle of well-placed wisdom. The jewellery business is truly a world with multiple facets.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana, Inc., a Montréal-based company working in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached at rippanainfo@gmail.com.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana, Inc., a Montréal-based company working in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached at rippanainfo@gmail.com.