DiCaprio, mountain lions, and lab-grown diamonds

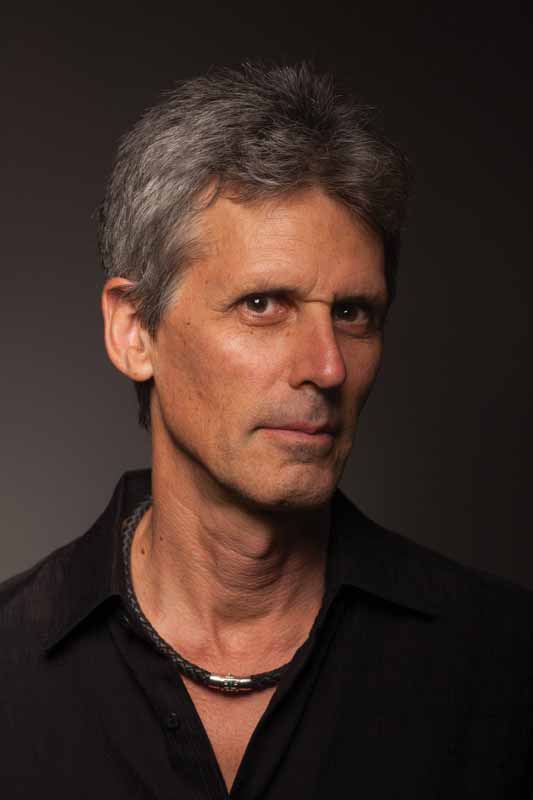

By Marc Choyt

Photos courtesy Marc Choyt/Reflective Jewelry

Leonard DiCaprio, known for his environmental activism, has been an influencer in the jewellery world since 2006—the year Blood Diamond was released. A few years after the film debuted, DiCaprio used his celebrity and financial collateral as a primary investor in the Diamond Foundry, a San Francisco-based firm.

Recently, DiCaprio was in the news again for helping to fund a Diamond Foundry plant in Spain, which he says aims to further “sustainably growing diamonds without [the] human and environmental toll of mining.”

Indeed, the Diamond Foundry’s process converts harmful methane gas to diamond with zero emissions. This is a unique selling point to the environmental and socially concerned shopper, which helps differentiate the company from perhaps dozens—even hundreds—of other firms now manufacturing lab-grown diamonds.

On the ground

Sector-wide, lab-grown diamond purchases are in the 50 per cent range and rising, while the price of their natural counterparts is in steep decline in a difficult market. Rapnet, in one of its six stories that will shape 2023, noted that consumers continue to want “proof of origin and ethical sourcing,” and that the bridal market is emerging as a “surprising sweet spot for the [lab-grown diamond] segment.”

Bridal is the heart of this author’s business, and lab-grown diamonds have become about 95 per cent of my total diamond sales. While the price of lab-grown diamonds has fallen considerably, the margins remain high—at least for now. In my experience, gen Z and millennial shoppers love lab-grown diamonds and cite two main reasons as to why this is the case. First, they simply don’t trust claims of “conflict-free” stones (even though I offer Canadian-sourced diamonds); second, they appreciate the high carat count they can get for their buck.

Essentially, what my customers are looking for is an experience of value and coherence. Diamonds have their allure, of course, but shoppers want to know that the exchanging of rings—a tradition started by the Egyptians 3,000 years ago—isn’t destroying their future, and, rather, is a worthy symbol of their love.

Not once has anyone ever mentioned carbon impact as a factor in their lab-grown diamond purchase. Should they be concerned?

Carbon impact

The International Gem Society (IGS) estimates a natural diamond emits 160 kg of CO2 per karat, which is based upon moving 250 tons of rock. On the other hand, a single-carat lab-grown diamond produces 511 kgs of greenhouse gases (GHGs).

To put these numbers in perspective, an average house in the United States produces 131 kg of GHGs each day—so, 3.5 days of living emits the same as a one-carat diamond. Flying produces 0.25 tons of CO2 per hour, which is also roughly the equivalent of a one-carat lab-grown diamond.

What both lab-grown diamond marketing and the IGS statistics seem to ignore, though, is the carbon impact of small-scale diamond mining, which is roughly 20 per cent of the global supply chain.

The Marange fields in Zimbabwe, for example, were producing 30 carats a ton in alluvial fields, just under the surface. Marange, of course, was the site of all forms of human rights abuse, though the diamonds were ultimately certified as “conflict free.” Carat per ton of rock in both large- and small-scale diamond mining varies, but, with small-scale mining, a carat of material in a ton or two of rock is not uncommon.

What is the carbon impact of people shovelling in the earth? Not much—yet, the plight of small-scale miners, whose lives are characterized by exploitation and poverty, are somehow overlooked by IGS and the lab-grown diamond sectors, as well as by jewellers who market these stones as the ideal “eco-friendly” and “conflict-free” option.

Leo the Lion

“We are running out of time and it [is] now incumbent upon all of us—all of you, activists, young and old—to please get involved because the environment and the fight for the world’s poor are inherently linked,” says DiCaprio. “The planet can no longer wait; the underprivileged can no longer be ignored. This is truly our moment for action—please, take action.”

In Latin, “Leo” translates to “lion.” The name conveys bravery, courage, and nobility.

When I think of lions, I don’t think of DiCaprio. I think of the mountains in northern New Mexico, at the southern tip of the Rocky Mountains, where I live and hunt.

A few years ago, I was hunting elk at 11,000 feet with a muzzleloader. It was late November, with two feet of snow on the ground and freezing temperatures.

Twenty minutes past sundown, I took down a cow with a clean, double lung shot. I pulled out my knife and began the work—slicing down the centre of her underside. I had to be quick. I’d forgotten my flashlight and the temperatures were dropping by the minute. Soon, it was dark, and I was shaking uncontrollably. My knife was too dull. I held the sharpener up in the air and began running the blade through it when it slipped and sliced a gash through my index finger.

Bleeding heavily, I taped a glove over my hand, finished removing the animal’s entrails, and walked down the mountain where I met my hunting buddies who took me to an emergency room.

The next day, we walked back up almost a thousand metres with backpacks. Mountain lion tracks. “It’s fine to share,” I told my friends. We boned out the meat we could salvage, and it was certainly enough to fill my freezer for the winter.

The lion is a keystone species, which, through its very life, supports the health and resiliency of the entire natural cyclical ecosystem. Similarly, the diamond industry is the keystone species of the jewellery environment, but with one key difference: It is extractive to communities and exists to transfer wealth from producer from the bottom of the pyramid—the producer communities, the small-scale miner—to the top.

The birth of the ethical jewellery movement

Back in 2006, I attended JCK. It was about five months before Blood Diamond was released.

While at the show, I sat in on what was, perhaps, the first Fair Trade jewellery meeting. Martin Rapaport spoke of his valiant attempt to launch a fair-trade diamond supply chain out of Sierra Leone.

Occurring simultaneously was another event, which took place in a large conference room, packed with hundreds of people. The focus of this meeting was, essentially, how to protect the bottom line through consumer-facing strategies (i.e. the Kimberley Project [KP] “conflict-free” narrative) to mitigate the impact of Blood Diamond.

Over the years, we have seen how ineffective KP has been in changing conditions on the ground, as well as how impactful it has been as a marketing approach. This effectiveness, however, has gradually eroded. At the very least, the gen Z and millennial consumers I encounter do not believe the conflict-free narrative.

It is true, though, that we have seen some symbolic improvements in the industry. Botswana, for instance, recently threw off a few of De Beers’ shackles to get a better economic deal. De Beers funds the Diamond Development Initiative (DDI) instead of paramilitary groups, such as the apartheid-oriented paramilitary outfit, Executive Outcomes. Back in 2008, Ian Smillie referenced DDI’s potential to produce a fair-trade diamond. Of course, this has not happened yet—plus, the DDI is entirely unscalable.

Meanwhile, Alrosa, which is no longer the vice-chair of the Responsible Jewelry Council (RJC), continues to fund the war against Ukraine. Diamonds still flood into India, where they are polished up and sold as conflict free.

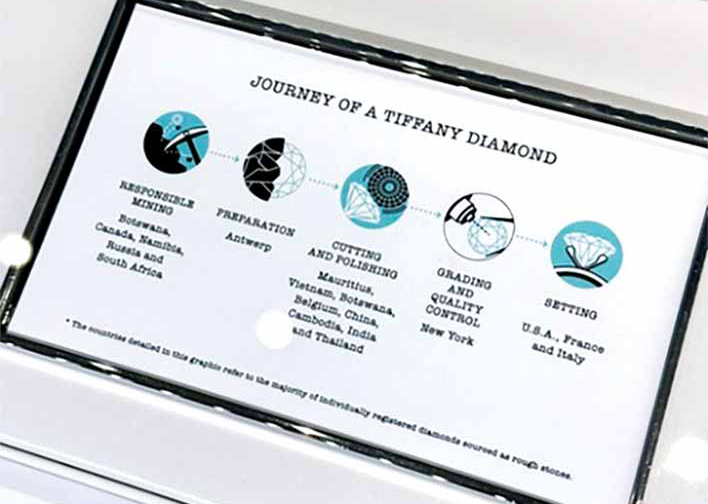

In Figure 1, we see the “Journey of a Tiffany Diamond.” This photo was taken at Tiffany & Co. in New York one year after the invasion of Ukraine. Often held up as the most exemplary company for ethical sourcing in the industry, in this instance, Tiffany markets its diamonds as coming from Russia.

By what criteria are Alrosa’s diamonds “ethical” and conflict free, considering Russia’s actions in the Crimea and its human rights abuses, even before the invasion?

To expect the diamond industry to really care about ethical sourcing in a manner that would impact how it has been doing business for the last hundred years is like expecting a mountain lion (or myself, for that matter) to become a vegan. The lion loves fresh elk liver. I love elk meat. The diamond industry loves money.

End of story? Almost.

“Oh, Leo, where art thou?”

The perception of lab-grown diamonds as a viable, economic, alternative gemstone option is just one more nail in the coffin for the small-scale diamond miner—which is what makes DiCaprio’s positionality a perfect fractal of the diamond sector’s predator nature.

Imagine if he had taken on the plight of the small-scale miner instead of investing in lab-grown diamonds. DiCaprio has a megaphone, along with a wallet big enough to make a difference to the people of Sierra Leone and other small-scale mining communities, trying to create a mine-to-market, small-scale diamond supply chain.

It’s not easy. I personally know of four failed attempts (and tens of thousands of dollars squandered) to start up projects with small-scale diamond mining communities—I was involved with one myself that never got off the ground.

Yet, while gen Z and millennial consumers would definitely support an ethical, fair trade-based, small-scale diamond supply, this massive energy potential for change has been subverted—namely, by the KP Certification process (which, in the words of even Martin Rapaport, is “bullshit”) and by lab-grown diamonds.

I truly appreciate the approach of the Diamond Foundry—it’s one of my suppliers. Still, DiCaprio is complicit, under the guise of eco-friendly carbon offset, in supporting the industry’s pivot away from historical atrocities. His investments bypass its structural inequalities among producer communities that are so environmentally and socially destructive (as the film he starred in so powerfully portrayed).

What we are left with, as ethical jewellers who are truly concerned about the connection between poverty and environmental destruction, are lab-grown diamonds, which, in context to an ethical supply chain, is worse than chopped liver.

Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry, a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds, is available online at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry, a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds, is available online at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

Columnists’ opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Jewellery Business.