A heated question: What Canadian jewellers should know about tanzanite

by charlene_voisin | August 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Branko Deljanin

[1]

[1]When tribesmen in Tanzania first presented violet crystals to trader Manuel de Souza in 1967, he didn’t realize what they’d discovered was a new gemstone. Instead, he believed he was looking at unusually coloured sapphires. As the story goes, lightning hit the ground near the city of Arusha, transforming brown crystals into a new and beautiful blue-violet colour. This accidental ‘heat treatment’ by nature may well be the factor that helped bring out the stone’s best colour. It also introduced the world to what would later be named tanzanite, the fifth bestselling stone in the gem trade.

Small- to medium-size tanzanites are commonly found in jewellery stores, almost all of them heated to achieve a violet-blue to bluish-violet colour. Our laboratory recently examined a few large tanzanites (i.e. bigger than 30 carats) to determine whether their colour was natural or enhanced through heating. Natural colour in larger-size tanzanites impacts value, and a lab report confirming no heat in tanzanites over 25 carats goes a long way to generate interest in collectable rare stones.

It is generally known and accepted that tanzanite is heated to achieve its distinct colour. Based on gemmological literature and our own research, we know this stone can, on occasion, be differentiated from unheated stones based on its UV-VIS-NIR absorption spectra and difference in pleochroic colours. However, the quest to find additional criteria to prove that some tanzanite can exhibit natural colour remains the subject of ongoing research of labs, such as American Gemological Laboratories (AGL), GGTL-Gemlab Laboratory, and Swiss Foundation for the Research of Gemstones (SSEF), as well as our own.

Control issues

[2]

[2]In April 2005, TanzaniteOne Mining announced it had acquired the mining licence to a significant portion of the tanzanite deposit known as ‘Block C.’ Since then, rough prices have increased steadily, as the company solidified its control of the market, which is believed to be 40 to 50 per cent of total output. Some of the rough goes through its official channels, which are made up mostly of American sightholders, but some is traded in the secondary market through smaller independents.

The mine currently has an estimated life of up to 20 years, producing about 2.2 million carats every year. Mining tanzanite nets the Tanzanian government approximately $20 million US annually, with most of the finished gems ending up in the U.S. market and sales totaling about $500 million US annually. In 2010, the Tanzanian government banned the export of rough bigger than five carats to spur the development of local cutting facilities and thus, boost the economy and potential for profit from a major natural resource. However, an estimated $400 million worth of tanzanite is cut in Jaipur, India. Rough is also being cut in Thailand, Germany, China, and, of course, Tanzania.

Riot of colour

[3]

[3]The world’s largest faceted tanzanite is 737.81 carats, although the 242-carat ‘Queen of Kilimanjaro’ is one of the most famous. Set in a tiara, the stone is accented with 803 brilliant-cut tsavorite garnets and 913 brilliant-cut diamonds, and is part of the private collection of Michael Scott, who was the first chief executive officer (CEO) of Apple Computers.

Tanzanite in large sizes is readily available, says Alex Barcados of C.D. Barcados Co., in Toronto. “It is easier to find stones in deep rich colours in the larger sizes (10 carats and greater) than smaller ones of less than two carats. I find there is little or no size premium in the per-carat price for pieces over three carats. It used to be that a predominately blue face-up colour was the most sought-after, but the market seems to look equally for purplish to bluish colours, provided they are as vivid as possible.”

To date, there is no universally accepted method of grading coloured gemstones, although TanzaniteOne has introduced its own colour grading system, which divides tanzanite colours into hues ranging from blue-violet to violet-blue. In testing tanzanite at our lab, we have noticed that stones bigger than 10 carats are generally richer and deeper in colour.

Clarity grading in coloured gemstones is based on the eye-clean standard, that is, a gem is considered flawless if no inclusions are visible to the unaided eye. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA) classifies tanzanite as a Type I gemstone, meaning it is normally eye-flawless. We have found a few tanzanites with fractures. Like any other gem, this stone can be clarity-enhanced with oil, although it is a very rare practice.

Treatments and disclosure

[4]

[4]Tanzanite is heat-treated in a 550 C to 700 C furnace to produce a range of hues between bluish-violet to violet-blue. Some stones found close to the surface in the early days of the discovery were gem-quality blue that required no heat treatment. Ideally, stones should not have any cracks or bubbles, as they can shatter the gem when they expand in size.

Heating is done in Tanzania and likely also in India. Lisa Elser of Custom Cut Gems travels to Tanzania to buy rough, but cuts it at her workshop in British Columbia. “Heating is usually done after cutting, although some miners use wood fires to heat the rough,” Elser explains. “It does not take very high heat to change tanzanite from its brown/yellow colour to blue/purple. Heating is assumed, so jewellers always have to disclose heat treatment at point of sale.” Since heat treatment is common, it has no effect on price of finished gems in sizes less than three carats.

More recently, undisclosed tanzanites coated with a thin layer of cobalt and other elements to improve durability began appearing on the market and in laboratories. The coating can be detected using X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. It should also be noted that since this treatment is not permanent, it must be disclosed at the point of sale.

Gemmological testing of tanzanite

[5]

[5]Tanzanite is a soft stone, measuring 6.5 on the Mohs hardness scale. The dichroscope is a great help in identifying loose and mounted tanzanites, as the gem has characteristically strong pleochroism (i.e. a crystal exhibiting different colours when viewed from various angles). Only unheated tanzanite exhibits trichroism (namely blue, purple, and yellow), whereas all heated stones are dichroic, displaying blue and purple. Purple is a modified spectral hue that lies halfway between red and blue.

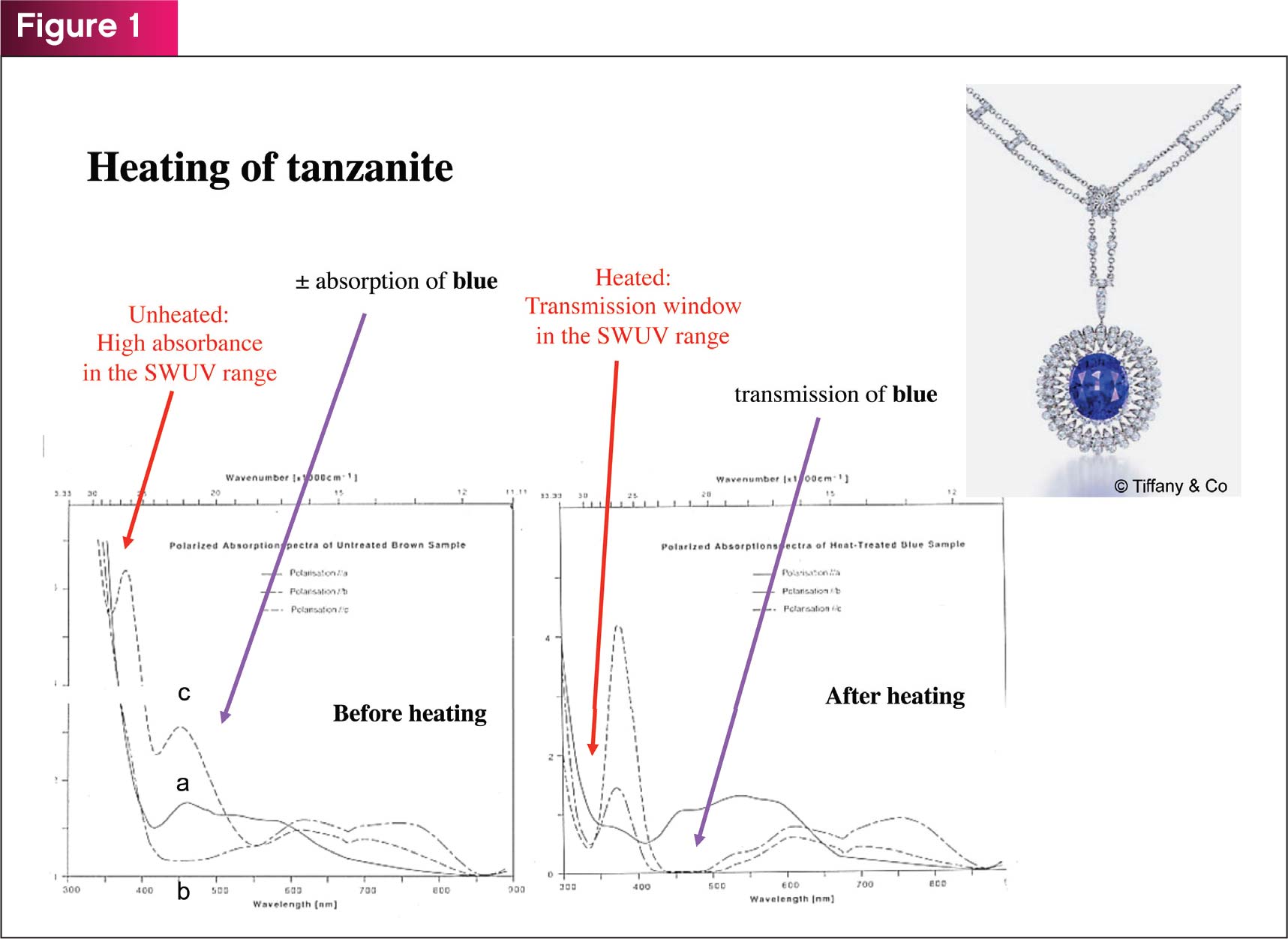

Figure 1 shows the difference between heated and non-heated tanzanite using UV-VIS-NIR spectra. The main criterion is a transmission ‘window’ in the shortwave UV range. It is generally beneficial to analyze along the blue pleochroic direction to see the transmission window the best. After Notari et al. (2001), it also became possible to measure the spectrum unpolarized; if the stone is heated, it transmits light from 300 to 400 nm in the UV part of spectra.

At this time, we can suggest the identification of natural-coloured tanzanite is far more difficult than what some gemmological publications would have us believe based on UV-VIS-NIR spectroscopy criterion proposed many years ago by European researchers.

The question for traders and jewellers remains whether they should disclose tanzanite as heated or just state that it is ‘natural tanzanite’ at the point of sale and say it is not possible to prove or disprove heat treatment. Our policy is to indicate ‘Not detectable’ under ‘Enhancement’ on the report, with the additional qualifying statement that ‘Most tanzanites are heated to improve colour.’ In the rare case where we can prove natural colour, we state that on the report.

Gemmological testing at most labs may not be fully conclusive with current technology, so further research into the testing of non-heated material should be a challenge worthy of consideration for top labs. Perhaps a spectra database would be a good starting point.

“The laboratory grading of tanzanite is still in its early stages, and the tanzanite industry as a whole is not sophisticated enough to absorb a market that requests natural-coloured tanzanite as a preference,” says Hayley Henning of TanzaniteOne Foundation. “We are starting to see this, however, but in general, consumers are still obsessed with violet-blue tanzanite, which is generally known to be heated as a part of bringing out the natural beauty of the stone.”

At the counter

[6]

[6]Durability is one of the main aspects regarding tanzanite of which jewellers should be aware. First, tanzanite is fragile and can break easily during the manufacturing process (i.e. thermal shock, physical damage, etc.). In addition, consumers should also be clearly informed of its durability when it comes to daily wear. Tanzanite is a very beautiful gem, and while some people can wear it in a ring, those with active lifestyles may want to consider another stone. It is an especially poor choice for an engagement ring, which is generally worn every day. Instead, it is most often used in a pendant.

Jurie Wessels of Gem Connection in Vancouver believes tanzanite is easy to market. “It is a good-looking stone with a great story that is still relatively inexpensive. It is easy to source and provides a great esthetic alternative for fine-quality blue sapphires.”

Tanzanite prices have been stable for several years. According to TanzaniteOne, retail prices range from $400 US per carat for exceptional to moderate stones smaller than one carat to $1100 per carat for those bigger than 50 carats. The ‘best’ values in tanzanite are in the larger sizes (i.e. five carats and bigger) and in the top qualities. However, there is not as much of a premium for top material compared to medium-quality material in other gemstones like rubies, emeralds, or sapphires. Since tanzanite is a softer stone, one often sees poorly finished cutting; a well-cut and polished tanzanite really showcases the material’s fantastic beauty.

[7]

[7]“When it comes to tanzanite, private buyers with the ability to acquire large pieces seem to be unwilling to compromise on quality,” says Amir Durrani of Federal Auction House in Vancouver. “Generally, people are looking for a combination of large size, excellent colour, and clarity, and if possible, unheated. Tanzanite buyers like the fact this stone is a thousand times rarer than diamonds, and that it has a single mining source.”

In conclusion, tanzanite is not the only gemstone that is commonly treated. Most aquamarine is heated and blue topaz is routinely irradiated. Further, these stones share a very important characteristic: the extreme difficulty to prove treatments with microscopy or advanced gemmological techniques available in most laboratories. Nevertheless, well-informed wholesalers and jewellers should apprise their clients about common practices regarding the enhancement of gemstones. This is particularly important when a stone does not have a certificate or the certificate does not clearly indicate whether the stone is treated.

The author would like to thank Alex Barcados of C.D. Barcados Co., Lisa Elser of Custom Cut Gems, Amir Durrani of Federal Auction House, Jurie Wessels of Gem Connection, Michael Krzemnicki of Swiss Gemmological Institute, Hayley Henning of TanzaniteOne Foundation, and Bill Vermeulen of the Canadian Gemological Laboratory (CGL) for their contribution to this article.

[8]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and president of Canadian Gemological Laboratory (CGL) in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[9].

[8]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and president of Canadian Gemological Laboratory (CGL) in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[9].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig-5-Four-TANZANITES-ranging-in-colour-from-lighter-under-10ct-an-dadrker-bluish-violet-in-sizes-over-10ct.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/120309-tte-arusha-1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig-3-Crystal-from-Merelani-Tanzania-showing-yellow-pleochroic-colour.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig-4-Tanzanite-unheated-blue-pleochroism.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig11.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig-7-23ct-Violetish-Blue-Tanzanite-Oval-Cabochon-Heated.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig-1-34.72ct-Heated-bluish-violet-LEFT-and-44.79-ct-unheated-violetish-blue-tanzanite-RIGHT-Federal-Auction.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Branko.jpg

- info@cglworld.ca: mailto:info@cglworld.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/a-heated-question-what-canadian-jewellers-should-know-about-tanzanite/