AGS Laboratories: Protecting consumer confidence one diamond at a time

by Sarah Manning | September 28, 2016 9:36 am

By Jacquie De Almeida

[1]

[1]The first time Jason Quick laid eyes on the Esperanza diamond, he was awestruck by the way light moved through the rough crystal. It was love at first sight, as he puts it, a once-in-a-lifetime encounter with the 8.52-carat diamond unearthed at Arkansas’ Crater of Diamonds State Park.

Quick, who serves as director of AGS Laboratories (AGSL), has seen many diamonds over the years, but few have left the same impression as Esperanza, he says. “The rough had curves and you could see how light moved through it. The crystal bent light around the surface of the diamond. It was absolutely mesmerizing.”

Esperanza is one of millions of diamonds that have passed through AGS Laboratories’ doors in the 20 years since its founding. Its journey from rough to polished is also one of the rare occasions when everyone involved is a member of American Gem Society (AGS). That includes Canada’s own Embee Diamonds, which cut the stone into a 4.60-carat triolette, which AGSL graded D-colour, IF. It was a feel-good story amid challenging times for the diamond industry, and came with its own in-store diamond-cutting event that was broadcast online.

“I think this story contributed to the excitement of what makes diamonds so special,” Quick adds.

The meticulous attention given to polishing each of Esperanza’s 147 facets evokes the exacting standards at the heart of AGSL’s founding. It was the early 1930s when Robert M. Shipley set out to help educate American jewellers in the tradition of organizations like Gemmological Association of Great Britain (Gem-A), where he had studied after realizing his own knowledge of diamonds and coloured gems was lacking. In 1931, he established Gemological Institute of America (GIA) in a small Los Angeles office and three years later, he founded AGS, a non-profit organization whose goal was to create high ethical standards in the jewellery industry to help ensure consumer confidence.

In the years that followed, AGS focused in part on research, culminating in the launch of the AGS Diamond Grading Standards Manual in 1966. It was the first published manual comprising a grading system for the 4 Cs, including cut. Thirty years later, AGS established its own laboratory with a mission of consumer protection, as well as research and development. In 2005, AGSL introduced its light-performance cut grade, which Quick was instrumental in helping develop.

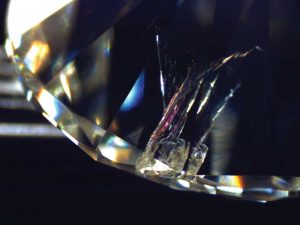

Since then, the world of diamond grading has changed significantly, particularly in the rise of lab-grown stones entering the market. Few take issue with their ability to present consumers with an alternative choice when disclosed. It’s when they are undisclosed that an alarm is sounded. The issue spurred AGSL to introduce its Natural Diamond Verification Service earlier this year. Every loose diamond .18 carats and bigger that comes to the lab for grading is put through full testing to ensure it is of natural origin. In addition, the stone is tested to determine whether it was high-pressure/high temperature-treated (HPHT-treated) to improve its colour. Quick says the danger of undisclosed lab-growns is a particular concern among retailers who buy back diamonds from consumers.

“Recycled diamonds is a big part of the inventory that is out there, and retailers don’t have the equipment or the expertise to do full testing for all the stones they may be buying from these non-standard channels,” he explains.

[2]

[2]Grading practices have also come under scrutiny in recent years. The very subjective nature of grading diamonds—particularly when it comes to colour—is the reason why some labs, including AGSL, require more than one grader examine a stone. At AGSL, a minimum of two people grade a single diamond. If there is disagreement between them, the stone is referred to other graders. To help ensure greater accuracy, AGSL graders go through rigorous training processes where their conclusions are compared to that of the lab’s most senior and experienced diamond graders.

Quick says the grading controversy has created broader awareness among the trade and the public, helping to highlight the transparency that is critical to ensuring consumer confidence.

“From the point of view of the industry, having these discussions is a good thing,” he explains. “Consumers get to learn more about what a grading report is and what the grading standards are. It helps create more consumer awareness to use a diamond grading lab they can trust to provide a third-party unbiased opinion of a diamond.”

The challenge for retailers these days, Quick says, is to differentiate themselves from their competitor and move diamonds out of the perception they can be sold as a commodity. As a former graduate school student with an eye on becoming a math professor, Quick’s take on diamonds is surprisingly less about proportions and angles and more about appreciating them for their artistry.

“To me, it makes a lot of sense to buy diamonds for what they are and to have their cut and beauty be part of that,” he explains. “Diamonds fall in the space of art—they are sculptures that are cut to be beautiful.”

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/25-C34B0953.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/1-Fracture-Filled.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/ags-laboratories-protecting-consumer-confidence-one-diamond-at-a-time/