Inclusions

Photo courtesy Sam Woehrmann

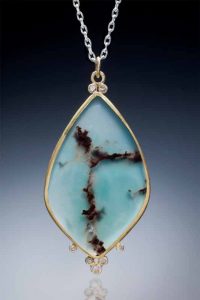

This greenish-blue gemstone can be free of inclusions and clean, or it can come in a million different patterns when cut with inclusions. The inclusions often fall in the brownish to white colour range, offering an interesting contrast with the blue. Designers who work with it often prefer gems with inclusions over clean ones, because the included material is easy to work with and makes the gem look organic. However, collectors from all over love the clean material that offers a vibrant blue.

Everything that comes out of the mines is bought, whether it is of ‘low’ or ‘high’ quality. This is an ethical way to ensure miners get enough money for what they mine and there is enough material on the market. It also means the material is not only known for its highest quality. The organic look of the included gemstone presents a vast opportunity to the market and reflects the fact not only perfect specimens can have beauty and a story to tell.

Treatments

Aquaprase is as stable as it gets. No oil (as is used for emerald), dye (often seen in lapis lazuli), impregnation, or stabilization (as applied to turquoise or opal) is used on it. This stone neither requires nor responds to any treatment available today. It offers 100 per cent natural beauty.

The fight that started it all

Yianni Melas, a Greek influencer in the gemmology world and an advocate for human rights, is the one who discovered the gem and named it ‘aquaprase.’ The term ‘aqua’ represents the blue of the Greek Aegean Sea. ‘Prase,’ which means ‘leek’ in ancient Greek, reflects the colour green. Melas is also trying to get the stone approved as a January birthstone, since it was discovered in January.

Photos courtesy Yianni Melas

The gemstone first came out because of a fight with gemmological labs. The first laboratory that came across it was a major Swiss lab, which identified it as chrysoprase. Since the colour was nothing like chrysoprase (being more of a blue-green than a yellow-green), Yianni Melas was unconvinced. He fought for a new diagnosis and brought the stone to the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) for a final identification.

The institute later revealed it was a new type of chalcedony. (To read the article in which the Gemological Institute of America [GIA] identifies the gem, click here.) The colour is so unique, it could not be attributed to chrysocolla or chrysoprase. The chemical composition and certain tests also helped determine this was a different gemstone.