Are you selling under-karated jewellery?

by charlene_voisin | July 1, 2014 9:00 am

By Jacquie De Almeida

[1]

[1]When Greg Merrall’s students called him over to look at what they’d found, he knew right away it certainly wasn’t silver. Although the coins they had purchased from a Toronto supplier carried the appropriate stamp, once melted, the metal neither looked like 999 silver nor acted like it. Merrall—co-ordinator of the jewellery arts program at Georgian College—wasn’t surprised though. He’s heard stories over the years of under-karating, some more disturbing than others.

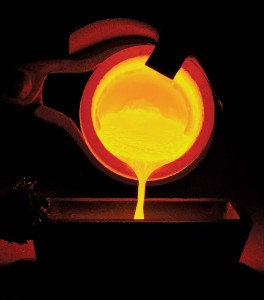

With more manufacturing happening outside Canada, the likelihood of under-karated jewellery entering the country is a real concern. The problem is, destructive fire assay is the most reliable way to conclusively determine an alloy’s composition. Expensive X-ray fluorescence is another option, though likely cost-prohibitive for most. To add to that, with apparently little to no oversight on the part of the government, you have to wonder how big a problem under-karating really is.

“We didn’t do an assay of the coin material, but it was fairly obvious it wasn’t sterling silver and it was clearly stamped as being that,” says Merrall, adding the incident happened last fall.

“It was a large coin from the Orient. When we took the coins back, they just exchanged it. They didn’t hesitate at all and they didn’t seem surprised. They get so many coins that they’re not going to test every one of them.”

‘An undiscovered problem’

[2]

[2]According to Canada’s Precious Metals Marking Act, a precious metal item is not required to have a quality stamp. However, if it has one, the act says the piece must carry a registered trademark.

Merrall—who also serves as a director at Jewellers Vigilance Canada (JVC)—says that years ago, inspectors would randomly visit retailers, buy a piece of jewellery, and test it to destruction. Today, it’s not clear if any similar testing is being done, although the general consensus in the industry is it isn’t. When contacted by Jewellery Business, the Competition Bureau declined an interview, writing instead the following in an e-mail:

“In terms of our current work in this area, the bureau is required to conduct its work confidentially; therefore, we cannot confirm whether there are any ongoing investigations. For the same reason, we cannot confirm whether we have received any complaints in this area. We encourage those who suspect a company is under-karating to submit a complaint to the bureau, as complaints help the bureau gather evidence as to whether a company or individual is in violation of the Precious Metals Marking Act.”

While the act allows for a variance of a quarter karat, Merrall says most would consider a two-karat discrepancy as under-karating. They would also consider it not an accident, given the amount of metal and numerous batches that have to be mixed for a large-scale production run. The feeling is that neither Canadian manufacturers/importers nor custom jewellers are the source, as the risk to reputation would be too great. Rather, the problem seems to be most prevalent among overseas operations.

Edmonton goldsmith David Keeling believes under-karating is “an undiscovered problem,” particularly when it comes to white gold jewellery. Rhodium plating is one way of disguising under-karated gold or even a base metal.

[3]

[3]“Unless each and every jeweller who is making purchases owns a karat analysis device, they are basically going on stamps,” he says. “With a lot of the white gold products imported from [overseas manufacturers] through Canadian companies, I don’t know whether those importers here would spend the effort on destructive testing to determine karating. I think the industry is so small here that there’s nobody willing to spend the money to guarantee the items are exactly as stated on invoices.

“If we have toys coming into the country that have poisonous paint and stuffing in them and these items aren’t caught initially by any sort of group that does testing on them—if that’s happening in the toy industry, which is absolutely massive, imagine what’s happening in the jewellery industry,” Keeling noted. “One could surmise there is under-karating going on. Is it a problem? I don’t know.”

Apel Camgozlu of Mary Jewellery, an importer based in Toronto, says he was a victim of under-karating three years ago. A purchase of about 300 rings and earrings stamped 925 silver from a Chinese manufacturer turned out to be silver-plated base metal. It wasn’t until a client returned a ring for sizing that they discovered the jewellery wasn’t silver through and through.

“They didn’t disclose the jewellery was plated,” he said. “We cut the ring and we could see the difference in colour. Once we figured it out, we sold the product as silver-plated and just didn’t order from them anymore. You have to deal with trusted companies, especially when you’re giving them your trademark to stamp on the product they make for you. We don’t sample our jewellery because we know who we’re dealing with.”

Camgozlu says he’s never had an incident of under-karated gold jewellery, but he has no doubt that it happens. “The Canadian market is probably better than the American market, plus we don’t do as much volume as they do,” he adds.

A different mindset

[4]

[4]The United Kingdom is one jurisdiction that takes under-karating very seriously. Dating back to the 1300s, the Goldsmiths’ Company Assay Office samples, assays, and hallmarks every item sold as a precious metal.

“It’s engrained into the psyche of the makers and the public,” Merrall says. “People would not consider for a second buying a piece of precious metal jewellery that doesn’t have the stamps on it. And if they did, they would fully understand there’s no legal imperative to it being what it says it is.”

Merrall says he’s not aware of anyone being charged for under-karating in Canada, but he has heard of small independents made aware the products they were selling were not what they were stamped to be. He is quick to point out, though, the incidents were accidental and not an attempt to defraud.

Steven Greenwald, owner of Toronto-based Supreme Silver and a partner in a manufacturing facility in China, has had a different experience overseas. He recalls visiting a local factory and seeing a number of boxes containing earrings that were stamped 925 silver.

“I was looking through the earrings and noticed they were all on earring hooks,” Greenwald says. “The owner of the factory came over to tell me they were not really ‘Silver 925.’ The only parts that were real silver were the earring hooks and they were stamped ‘925.’ The actual earrings were just a white alloy. Each pair of earrings was rhodium-plated to make it look like the whole thing was silver. I was surprised he was telling me this, but he said this is how the customer ordered it. The factory was not cheating the buyer—the buyer was cheating his customers. The goods were being shipped to the United States.”

Although Greenwald says he doesn’t personally know of any under-karated jewellery entering Canada, he believes it’s not a stretch of the imagination that if there is a problem in the United States, Canada is not immune. A quick Google search results in several articles of incidents of under-karating south of the border.

“I don’t think anyone really knows [how prevalent under-karating is],” he says, adding he’s aware of another manufacturer in China who made low-karat silver jewellery on request for a South American importer.

Merrall says he doesn’t believe under-karating is an epidemic, particularly on the part of Canadian manufacturers or importers who sell jewellery carrying both a quality stamp and trademark. The risk of a ruined reputation is just too great.

“I have no doubt that it happens, but if someone went into a legitimate retailer and bought a ring that has a legitimate trademark on it and a quality stamp, there’s a very good chance it is in fact what it says it is,” he says.

Breaking it down

[5]

[5]JVC executive director Phyllis Richard says the group has not received any recent consumer complaints regarding under-karated jewellery, but she is not surprised that it does happen.

“It’s always been an issue in our industry; it’s not that suddenly we’re seeing more of it,” she says.

“It’s very hard to quantify how big a problem it is in Canada. In terms of our own manufacturing, we have a few big companies here, but there isn’t a lot of it; they’re not the problem.”

Thelma Chuakay, managing director of Umicore Precious Metals Canada, says she’s been asked by the Competition Bureau to explain the refining process and how fire assay works. She says refiners don’t check whether metal submitted to them is under-karated. They simply receive the scrap, jewellery, or bars, for instance, do a fire assay, and produce a report based on the material’s composition.

“It’s not our responsibility to report that something is under-karated because we don’t know where it came from,” says Chuakay, who also serves as a JVC director. “Someone could have brought in bars that were made from jewellery, and who knows where they came from.”

Duncan Parker, vice-president of Dupuis Fine Jewellery Auctioneers, says he’s heard stories about under-karating in Canada and occasionally witnessed it when he was at Harold Weinstein.

“As far as I know, under-karating is not widespread, but it could be widespread because it’s an unproven thing and we don’t have an assay system in this country that is set out to verify the quantity of the proportion of gold in an item,” he explains.

A scratch or acid test is generally the method of choice for appraisers or jewellers to determine the karat of a piece, although it is not exhaustive or 100 per cent accurate. However, if a metal is two carats out from what it’s marked, these tests will show that.

“If it’s less than two carats out, it’s probably a judgment call and you may say ‘Tested to be approximately 18-karat gold’ [on the report],” Parker says. “However, you should be able to tell with a non-destructive test if it’s two carats out. If it’s one carat off, you probably can tell, but it’s not going to be absolute.”

Richard says regulations like the Precious Metals Marking Act are necessary to maintain consumer confidence. However, she is quick to add there is always room for improvement and proactive measures.

“If you’re importing, you have to know who you’re buying from,” she says. “In any industry, everybody has to keep on top of things in order for things to run more smoothly and for consumers to retain the confidence we’ve been working so hard to build within the marketplace. Anything we can do to fortify that or contribute to that is very important for the health of our industry.”

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/PandaPagodaMelt.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/bigstock-Wedding-ring-with-diamond-on-w-43170106.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/bigstock-Scrap-Gold-29741240.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/bigstock-Customs-Declaration-59925785.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/bigstock-Pouring-molten-gold-20850887.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/are-you-selling-under-karated-jewellery/