By Alethea Inns

Diamond treatments and enhancements have always been a concern for jewellers because of their ethical considerations, disclosure requirements, and potential impact on consumer confidence.

Not only do jewellers have to know exactly what they are selling, but they have ethical, regulatory, and even legal responsibilities to disclose any treatments or enhancements to the customer prior to the point of sale. The consequences are real, especially in our age of social media and instant news-making.

Diamond treatments and enhancements are neither good or bad. Gemmologists love treatments and enhancements—they keep us on our toes. As technology and science advance, so do the possibilities of how we can alter gem materials. The bad part of treatments and enhancements is how they may be used to deceive. That is why it is essential for gemmologists to understand the science behind the treatments, how they impact gemstones, and how to communicate those implications clearly and transparently.

Detecting treatments and enhancements often requires advanced equipment and expertise. Let’s explore some of the nuances of detecting diamond colour treatments so you know exactly when to call in the experts.

Treatment vs. enhancement

Many in the industry view “treatment” and “enhancement” to be the same, claiming they are both used to describe any artificial process that alters the appearance of any gem. I see their point and I respectfully disagree. There is a distinct difference between treating a gemstone and enhancing it. A treatment “fixes” a pre-existing issue, where an enhancement elevates a pre-existing characteristic. While yes, both treatments and enhancements are artificial processes that alter the appearance (or durability) of the gemstone, treatments have a different intended outcome than an enhancement. Not all treatments are enhancements, but all enhancements fall under the category of treatments. Regardless, both must be disclosed prior to the point of sale, in keeping with good ethics as well as regional guidelines and laws.

When it comes to diamonds, treatments and enhancements mostly target two of the 4Cs: Clarity and colour—and, in one instance, cut.

Coatings and thin-films

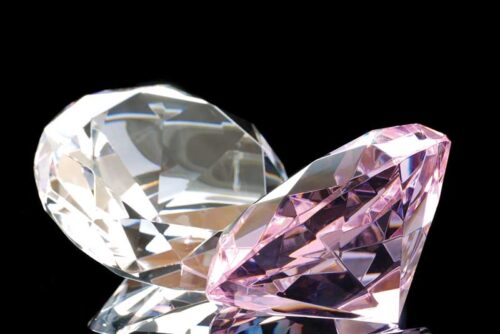

Colour is the most altered of the 4Cs because of the ease of the treatment or enhancement. Keep in mind, diamonds are not just treated to change the colour of a diamond to a fancy colour—or change the modifiers of a fancy colour (for example, removing the brownish modifier from an orangy diamond)—but also to improve the colour of a D-Z diamond. A blue or violet coating on a yellowish diamond has the potential to drastically improve the apparent colour grade.

The most primitive way to change the colour of a diamond is to coat it with some kind of paint, chemical, or foil backing. Coating, dyeing, or “painting” gemstones with foreign materials to create a more desirable colour has been occurring for centuries. Gemstones have been foiled since the first century CE—when Pliny wrote the first written account of the technique—and foil-backed gemstones can be dated back to the Minoan period (2000-1600 BCE).1

Coatings can be fairly durable but are not permanent. Coated diamonds can be damaged by heat and chemicals during jewellery repairs and polishing. They can also be scratched.

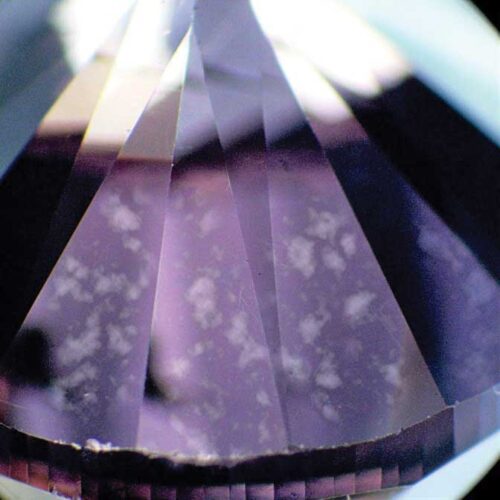

As science and technology advance, coatings, (and treatments in general) have become increasingly difficult to detect. Chemical coatings and thin-films can be a bit more complex, especially if you only have access to view the crown of the diamond and the coating or thin-film is confined to the pavilion of the diamond. Vacuum sputtered films, or an overgrowth of lab-grown diamond over a natural diamond are some examples of how advancements in science have been applied to treating diamond colour.

These treatments may often not be detectable by the average gemmologist and may need laboratory intervention. If you test diamond type in your business and your diamond colour conflicts with diamond type, you have a good indicator to send the diamond to a laboratory.

There have been rare cases where laboratory-grown overgrowth was deposited on a natural near-colourless (D-Z) diamond to cause a blue colour. Another indicator laboratories look for are pink diamonds showing as Type Ia with cape lines, which can indicate a regular near-colourless diamond having a pink coating. No pink graining in pink diamond is another warning sign to check the origin of colour.

Fortunately, “composite” diamonds with lab-grown overgrowth are still relatively rare and cost-prohibitive

to produce.

Annealing

Annealing (low pressure, high temperature) is a controlled heating and cooling process which is often used after irradiation to change a diamond’s colour to brown, orange, or yellow. It can also produce pink, red, and purple colours as well. When annealing is used by itself, it can change the colour in a series—generally blue to green to brown to yellow. The treatment is stopped when the desired colour is reached. If heat is later applied to an annealed diamond during routine jewellery repairs, it can drastically alter its colour. Most of the time, annealing is undetectable.

Natural black diamonds are black because of black masses and inclusions of graphite and other minerals that absorb light. Most black diamonds start as heavily included diamonds that are exposed to temperatures around 1,000 C, which further graphitize the fractures, turning them an opaque black. Like heated rubies, there are more annealed black diamonds on the market than natural, and the treatment is commonplace. It still must be disclosed.

Additionally, treated black diamonds can also be caused by artificial irradiation that results in a green so dark the gems appear black.

Here are a few TL;DRs:

|

Irradiation

In 1904, Sir William Crookes submitted a paper to the Royal Society of London explaining how packing diamonds in radium bromide for several months turned them a bluish green colour. This was the first time diamonds had been subjected to irradiation.

Subsequently, diamonds were subjected to cyclotron irradiation with different subatomic particles (alpha particles, deuterons, and protons) turning them to blues and greens, and yellows and browns (a result of the ambient heat from the process). Those who have undertaken a formalized gemmological education recognize these diamonds by their umbrella effect around the culet. As the nuclear race ramped up, and nuclear reactors become more prevalent in the 1950s, neutron irradiation was used to create a more uniform body colour in irradiated diamonds. This presented challenges to identification.

In short, radiation rips holes in the lattice of the diamond, and knocks carbon atoms out of place. These vacancies cause a change in how light is absorbed and transmitted, creating a different colour. Irradiation combined with annealing can also produce pink/purple, yellow, and orange diamonds.

Keep in mind, not only vivid fancy colour diamonds can be irradiated, lighter colours can also be subject to treatment. Look for unusual fluorescence reactions, zoning, colour concentrations. Look for classic colour origin characteristics like graining for pink and brown diamonds, patches of colour and their morphology, and make sure the diamond type makes sense for the colour of the diamond. Natural versus induced radiation is one of the hardest colour origin calls to make in gemmology. So, when in doubt, submit the stone to a reputable gemmological laboratory.

Irradiated diamonds are sensitive to heat, so jewellery repair procedures, recutting, and repolishing can change their colours. If you suspect a diamond has been irradiated, avoid subjecting it to high heats like a jeweller’s torch as this has the potential to alter the colour.

|

Treatment/Enhancement |

Process |

Purpose |

Care |

|

Coating |

Applies a thin layer to a portion of the diamond’s surface |

Colour. May improve optical properties. |

Non-permanent. Requires special care. Avoid chemicals, ultrasonic cleaners, heat. |

|

Irradiation |

Exposing the diamond to radiation alters the diamond’s atomic structure. |

Colour. Often used to create fancy-coloured diamonds. |

Mostly permanent. Avoid high heat like jeweller’s torch or sunlight. |

|

Annealing |

Heating at low pressure but high heat. Often used in conjunction with irradiation. |

Colour. Often to treat black diamonds, or change diamond colour to brown, orange, yellow, pink, red, or purple. |

Mostly permanent. Avoid extreme temperatures or exposure to radiation. |

|

HPHT |

Diamonds are processed using high pressure and high temperatures. |

Colour. Remove brown component or create fancy-coloured diamonds. |

Generally stable. Avoid extreme temperature changes. |

|

Laser drilling |

A laser is used to create channels or tubes to reach the surface of the diamond to fill or bleach the inclusions. |

Clarity. Improves apparent clarity by reducing contrast of dark inclusions. |

Stable. |

|

Fracture filling |

Surface-reaching inclusions are filled with a high-refraction material. |

Clarity. Improves apparent clarity by reducing difference in refractive index between diamond and inclusion. |

Unstable. Non-permanent. Avoid heat, ultrasonic cleaners, steam, or extreme conditions. May degrade with normal wear. |

|

Plasma etching |

Applies a nano-prism to the surface of the facet to create a diffraction grading. |

Cut. Improves apparent fire. |

Generally stable. Avoid repolishing the diamond. |

HPHT

High pressure, high temperature (HPHT) processing uses presses that apply extremely high pressures and temperatures to the diamond, similar to the formation conditions under the Earth. HPHT treatment uses similar equipment to those used to create lab-grown diamonds. The HPHT process can remove or change the colour depending on the diamond type and the optical centres and impurities in the diamond. HPHT is considered a permanent process.

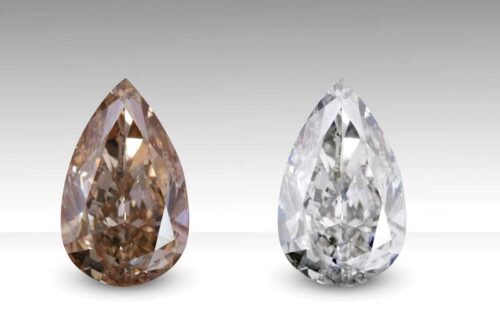

The most common purpose for HPHT treatment is to remove slight brownish tones from near colourless diamonds. This occurs by “healing” or restructuring plastic deformation and reorganizing defects in the crystal lattice that cause the brown colour.

HPHT processing can also turn brownish stones into other colours like yellow, greenish-yellow, or green. This process is also associated with pink and blue diamonds.

Given the process requires such high pressure and temperature, diamonds of higher clarities are the best candidates to reduce the risk of breakage.

Here are some of the outcomes related to diamond type:

- Brown colour diamond type Ia changes to yellow-green, or fancy yellow.

- Brown colour diamond type IIa changes to colourless or pink (in combination with irradiation)

- Brown/grey diamond type IIb changes to blue.

Combining treatments

More than one colour treatment may be done to a diamond. Irradiation and annealing is a popular treatment combination. Sometimes HPHT is followed with annealing and irradiation, which can yield pink-to-red to purple colours.

Common combinations include:

- Irradiation + very low-temperature annealing

- HPHT treatment + irradiation + low-temperature annealing

As consumers become more informed and socially conscious, the industry is challenged to adapt and prioritize ethical practices, ensuring diamonds continue to symbolize not only beauty, but also responsibility and transparency in their journey from the depths of the Earth to the hands of the beholder.

References

1 “The Early History of Gemstone Treatments”, Kurt Nassau, Gems and Gemology, Spring 1984: Ball 1950

Alethea Inns, BSc., MSc., GG, is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA). Her career has focused on laboratory gemmology, the development of educational and credentialing programs for the jewellery industry, and the strategic implementation of e-learning and learning technology. Inns is chief learning officer for Gemological Science International (GSI). In this role, she leads efforts in developing partner educational programs and training, industry compliance and standards, and furthering the group’s mission for the highest levels of research, gemmology, and education. For more information, visit gemscience.net.