Finding inspiration in pearl

by Samantha Ashenhurst | February 18, 2020 10:09 am

[1]

[1]Photos courtesy Llyn L. Strelau/Jewels by Design

By Llyn L. Strelau

The Owl and the Pussy-cat went to sea in a beautiful pea-green boat…

I have always loved working with pearls—especially baroque pearls. While others may daydream looking at clouds, I find it entertaining and inspiring to see what is ‘hiding’ in a pearl. Sometimes this is obvious; other times, finding the message in a pearl requires close inspection and a great deal of imagination.

[2]

[2]While examining the plethora of offerings at the United States Pearl’s booth at the Tucson Gem Fair, a large freshwater pearl caught my eye. I can’t explain it, but I immediately saw an owl in the pearl. To my delight, when I examined it closely and turned it around, I saw the other side (with some imagination) could be a cat.

At 65 years old, I attended elementary school in the days when we were required to memorize poetry—and, one of my favourite pieces, penned by Victorian poet Edward Lear, was The Owl and the Pussy-cat! I purchased the pearl on the spot, realizing it could perfectly illustrate the poem.

Indeed, some designs seem to spring forth fully ‘formed’ when the inspiration hits, and this pearl did exactly that. I could visualize a ‘pea-green’ boat (green gold, maybe with gemstone accents), floating on an ocean with the owl and pussy-cat pearl aboard. Of course, staying true to the poem, I’d have to incorporate a gold five-pound note, enclosing honeycomb and money. As the design progressed and more elements were added, I realized the project would require more time, energy, and imagination than originally expected.

The beginning

When I returned home, the pearl sat in my safe for a year or so before I got to work on the design. I thought I would make it a sculptural piece and enter it in the ‘Object of Art’ category for the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) Spectrum Awards. To that end, I decided to visit another Tucson gem show to find some of the other components I would need for the design.

[3]

[3]First on my list was a base for the sculpture, as the pea-green boat would need to be afloat on a ‘sea.’ My initial idea was to incorporate a massive, aquamarine crystal specimen—preferably one with some of the natural surface extant. While spending several hours wandering around a mineral specimen-centric gem show along the Interstate 10 in Tucson, I came across a couple of aquamarines that were suitable, but the price was simply too much for this project.

Determined, I switched my focus to larimar, which is about the most ‘ocean’-like stone one could hope for. However, the natural surface pieces somehow didn’t look right. While it was beautiful when polished, I was convinced I needed a more irregular surface and natural texture for this component of the design.

Low and behold, I came across a dealer with magnificent specimens of rough chrysocolla from Peru—eureka! I selected a beautiful variegated Caribbean-Mediterranean blue and green, complete with glittery calcite inclusions and a subtle surface texture to give the appearance of gentle ocean waves. The rough piece would require some trimming to convert it into a flat-based slab, but other than that it was perfect as found. Ultimately, I recruited the help of a local lapidary, who did a fine job cutting the slab.

Fine factors

My next tasks were achieved in several steps. First, I had to add gold and gemstone details to the pearl to reinforce the features of the owl and the pussy-cat. Initially, I didn’t want to add more than eyes for both, a beak for the owl, and whiskers for the cat, but, in the end, decided that to achieve full effect, I would need to include a tail for the cat and wings for the owl.

[4]

[4]I purchased tiny, oval cat’s-eye chrysoberyl cabochons for the kitten’s eyes, but found they were a little too big. Further, after some research, I learned cats’ eyes are actually round and, in some conditions, feature a vertical ‘line’ in the centre. The ‘eye’ in the chrysoberyls ran the wrong direction; however, my lapidary colleague was able to trim the ovals down into matching 3-mm round stones. I carefully drilled holes into the pearl, then correctly oriented the eyes and glued them in place. Fine round platinum wire was fused and manipulated to create the animal’s whiskers (and the suggestion of her mouth), then pegged and glued into the pearl. Her tail was modelled in wax and designed to wrap around her body with slight visibility on the opposing (owl) wide of the pearl, representing affection for her mate.

I tackled the owl’s eyes next, testing out several options before finally settling on two 3-mm faceted, black spinel beads. I inserted 24-karat gold wire ‘pupils’ into the drill-hole of the beads, framing the spinel with a textured yellow gold surround. Like the cat, the owl’s eyes were set into holes and drilled into the pearl.

The owl’s beak was carved from 18-karat yellow gold, then pegged and glued it into place. For his wings, I found a pair of 3D computer-aided design (CAD) models, which I manipulated, milled in wax, and cast in 19-karat white gold. The pieces were then pegged onto the pearl, and articulated with pins to allow for slight movement. Like the cat’s tail, they’re slightly visible from the opposite side, giving the cat an embrace from the owl.

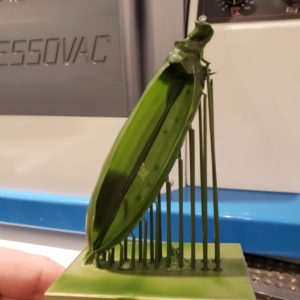

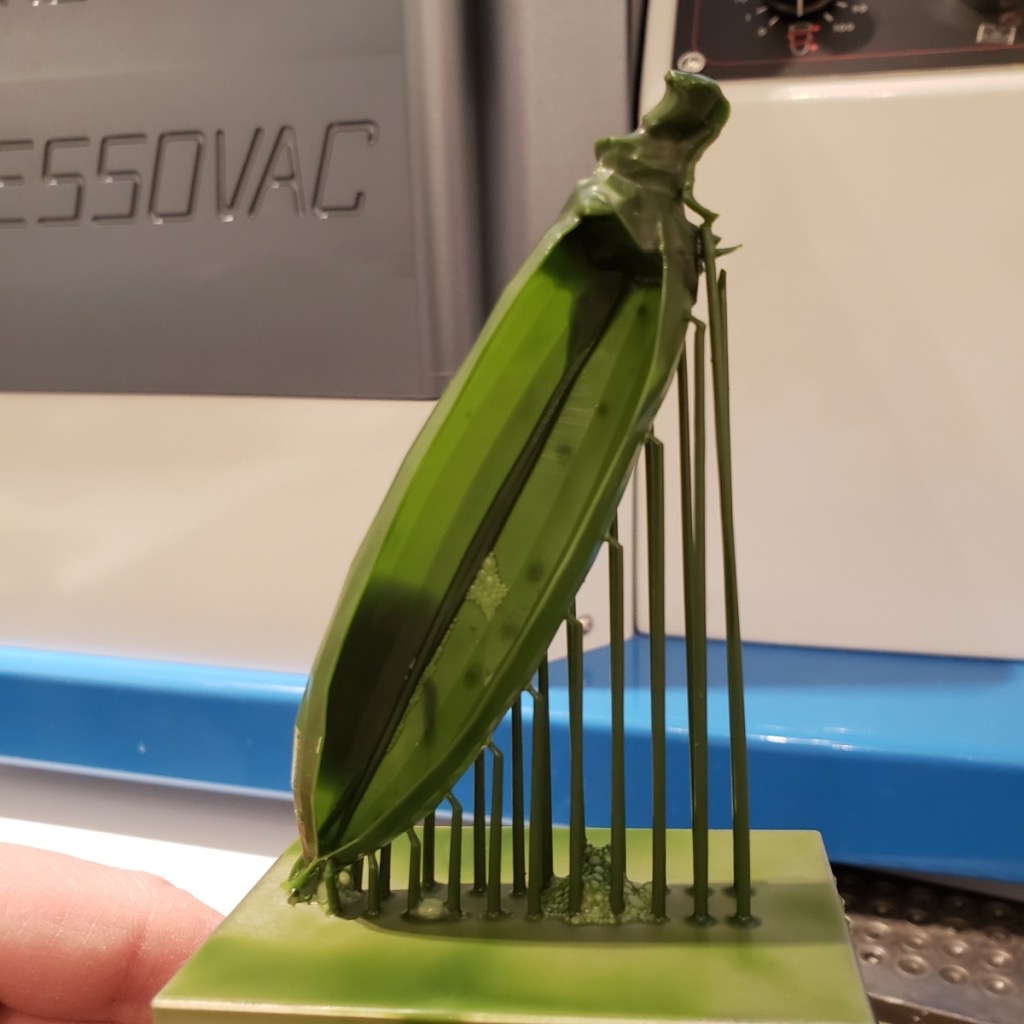

Crafting the vessel

As the poem reads, the owl and the pussy-cat went to sea in a pea-green boat. I decided the craft would have the form of a pea pod, and adapted a CAD model of a pea by enlarging and changing the proportions until it was a suitable vessel for its passengers.

The baroque pearl had a small ‘extension’ on its lower end. I decided to remove this, which allowed me to insert a female bayonet fitting. Meanwhile, the male bayonet fitting was installed in the base of the boat, so the pearl could be removed from the boat if desired. (A future project of mine will be to create a piece of jewellery, most likely a neckpiece, into which the pearl could be fitted and worn.)

The peapod boat was prototyped in resin, then cast in 18-karat green gold. To keep the weight to a minimum, the walls were only about 1 mm thick.

The calyx on the ‘stem’ end of the pea pod was grown and cast separately, then attached after finishing. The gunnel edges of the boat were left slightly thicker, allowing for 1.1-mm round, brilliant-cut light green tsavorites to be pavé-set along both edges. This task was challenging, as green gold (an alloy of pure gold and pure silver) is butter-soft and, while pushing beads was easy, the craft needed to be fully supported on the inside to prevent distortion or collapse of the walls.

Plenty of honey

[5]Following along with the poem, the design required ‘some honey, and plenty of money, wrapped up in a five-pound note.’ To achieve this aspect, I modelled a honeycomb using CAD, then milled it and cast the piece in 18-karat yellow gold. Small, natural fancy-coloured diamonds, the shade of honey, were set in a few of the comb’s cells, then tiny coin shapes were cut from white-gold sheet and engraved with small denominations of currency.

[5]Following along with the poem, the design required ‘some honey, and plenty of money, wrapped up in a five-pound note.’ To achieve this aspect, I modelled a honeycomb using CAD, then milled it and cast the piece in 18-karat yellow gold. Small, natural fancy-coloured diamonds, the shade of honey, were set in a few of the comb’s cells, then tiny coin shapes were cut from white-gold sheet and engraved with small denominations of currency.

Next, a thin rectangular sheet of 18-karat yellow gold was crafted and passed along to Warren Smith, a talented, British Columbia-based hand-engraver, who engraved the piece to look like a banknote. As a little joke, I asked him to etch in a caricature of my face with crown atop my head on one side of the note.

For assembly, I folded the gold banknote around the honeycomb and coins, which were then welded into place. Finally, the neat little package was secured onto the bow of the boat.

All about that base

While the vessel, its passenger(s), and its cargo were being fabricated, I shifted my attention to the sculpture’s base.

The chrysocolla piece was approximately 170 by 110 mm and, with the boat a little less than 100 mm long, this left a lot of open water. Rather than reduce the size of the sea, I opted to add a bit more to the scene.

The poem reads:

They sailed away, for a year and a day,

To the land where the bong-tree grows;

And there in a wood a Piggy-wig stood,

With a ring at the end of his nose…

Further to the tale, the owl purchases the ring from the pig and presents it to his bride, the pussy-cat, as her wedding ring (paid for with some of the money wrapped up in five-pound note).

With that direction in mind, I set off to create an island in the sea. I found a piece of stone (likely a form of porphyry) I had collected on one of my European vacations, which was dark green with pale inclusions and had a rough, textured surface. My lapidary sliced a piece off the top and this became the island.

Rather than a bong-tree, I opted instead to construct a palm tree on the island. I modelled the trunk in wax by hand before casting it in 18-karat rose gold. The palm fronds were hand-fabricated from thin sheets of 18-karat green gold and a goldsmith by the name of Jean van der Merwe fabricated a custom steel punch to add the veins of the leaves. The fronds, despite being quite thin and delicate, were welded together and fixed to the top of the trunk. The black and grey south sea keshi pearl coconuts were the suggestion of van der Merwe, and they were drilled and attached under the palm fronds.

To market, to market

[6]Crafting the little pig was both easy and problematic.

[6]Crafting the little pig was both easy and problematic.

For many years, I had in my (far too vast) collection of gem materials a small, carved rose-quartz pig with a tiny ruby eye. When I purchased it, I considered several design options, but nothing ever materialized. Though the item was a perfect addition for this project, there was one problem: it was only ‘half’ a pig (flat on the back and fully modelled on the front).

After much discussion, the design team and I decided to construct a white-gold polished back plate for the carving. This would help in keeping the colour of the delicate pink quartz clear, and also provide a method for attaching the pig to its island home.

We added some green gold foliage to the base of the palm tree, which gave us the metal needed for welding and attaching the pig’s back plate. A few tufts of gold wire grass helped further secure the pig in place. Finally, a small jump ring of pure gold was attached to the back plate and shaped to provide his nose ring. With that, we were set for the upcoming nuptials!

Setting sail

With all of the large pieces in place, a few finishing touches were still required.

Because I thought it unlikely the poem would be widely recognized by the millennial crowd, I decided to incorporate its title into the sculpture. I considered engraving the first line or two into the chrysocolla base, but, due to the irregularities of the surface, this was not feasible. Instead, I opted to add a sign-post to the pig’s island. Visualizing something a castaway might create, we crafted a sign of four rough-hewn white gold ‘planks,’ and the engraver then carved rustic letters into the boards with the poem’s title.

Finally, the boat required a sail. Using paper-thin platinum ribbons, I wove ‘mats’ in an over-and-under design, then trimmed it down. I attached the sail to a mast of white gold tubing, which was topped with a black south sea keshi pearl. Mimicking the tendril of a peapod, fine green gold wire was attached to the stem-end of the boat and spiralled to the top of the mast and sail, like rigging. As a final touch, I added a tiny diamond briolette dew drop, dangling from the end of the tendril, and a triangular purple sapphire flag.

The voyage begins

With the sculpture complete and all components pegged and epoxy-glued into their stone bases, my next challenge was to determine how to safely pack the piece to ship it to the AGTA Spectrum judges. Some last-minute fabrication issues caused delay (of course), but, fortunately, I had the option to ship my entry to New York City a couple weeks after the original Dallas delivery deadline.

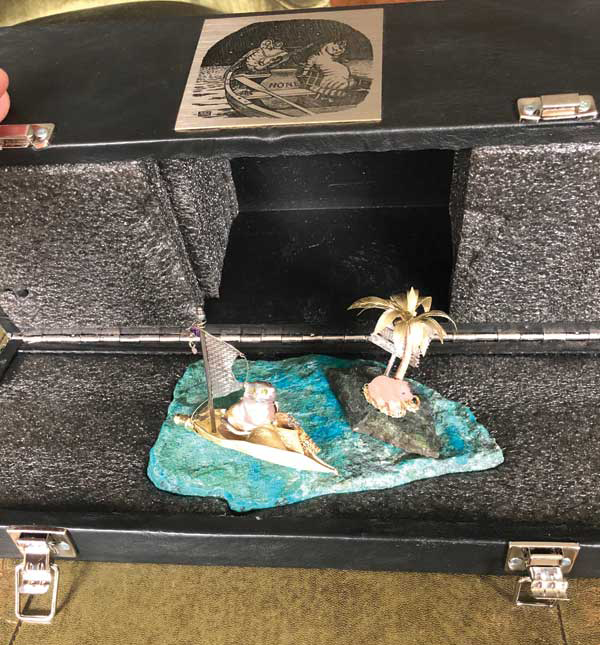

[7]When planning transportation, I started with a double-magnum size, hinged, wooden wine box. I opted to invert it and replace the hinges with stronger models before covering the case with black leather. Some secure flip-style latches completed the closure.

[7]When planning transportation, I started with a double-magnum size, hinged, wooden wine box. I opted to invert it and replace the hinges with stronger models before covering the case with black leather. Some secure flip-style latches completed the closure.

To hold the sculpture inside, I lined the interior with high-density foam. The bottom section (originally the shallow ‘lid’ of the wine box) was cut to fit the chrysocolla rock base, and I built up thick foam sections on the left and right of what was now the case’s cover. These foam pieces gave firm contact between the stone base and the cover, such that the stone was tightly held in place when the box was closed and latched. I was afraid to have physical contact with the owl/pussy-cat and the delicate green gold leaves of the palm tree, so I decided to leave them free.

To further re-enforce the sculpture’s connection to the Owl and the Pussy-cat, I had the text of the poem engraved on a metal plate, which was attached it to the lid of the leather-covered case. Then I had the inspiration to include an audio component and, using a small electronic circuit board, I uploaded a recording of the poem I had found online. A small button was fitted into the interior of the case and, when depressed, the poem would play.

Satisfied with my packaging, I took the case for a test run before sending it off, carrying the box around for a few days, shaking it, and turning it upside down. Everything appeared to be stable. I added a leatherette cover, a fitted inner-box, and a padded outer-box and the sculpture was finally ready to be shipped.

Late-game disaster

I had arranged for a colleague based in New York to accept the delivery when it arrived in the city and drop the sculpture off with the judges on my behalf. When my precious cargo arrived, however, the situation turned out to be a bit more complicated.

When the sculpture was unboxed, it was apparent two things went unaccounted in my packing strategy: 1) the power of inertia; and 2) the lack of delicacy offered by the courier. If I had been a bit more aggressive with my testing of the packaging before I shipped, I would have discovered that if the box was dropped from any height (or, in the case of the courier, tossed around like the proverbial football), the elements of the design that were not fully supported would move.

[8]

[8]Hence, when the box was opened, it appeared disaster had struck. Most components were lying loose; the shock of transit and rough-handling caused the pieces that were epoxied into the rock base to vibrate and detach. In retrospect, I should have found a method of supporting everything to avoid this result—perhaps by using bubble wrap or more pieces of high-density foam. I had considered these options when planning the packing, but was afraid they would be difficult for the competition staff to remove, and equally difficult to reposition for further shipping. My mistake!

Fortunately, nothing was irretrievably damaged and I was saved by my New York friend. Indeed, she went above and beyond, calling on the services of a talented goldsmith colleague who, after several video calls, emails, and phone calls, was able to put ‘Humpty-Dumpty’ together again. Then, my associate delivered the sculpture back to the competition in time for the judging deadline—most definitely ‘under the wire’!

Deliberation

Next came the waiting (and, hopefully, a phone call with good news).

Happily, my piece received recognition from the judging panel, earning an honourable mention in its respective category. While I would have loved to have taken first place, I’m more than content to place in what is a very competitive and difficult-to-judge event.

Having received the award, the next challenge was how to safely transport the piece to Tucson, where it would be displayed at the annual gem fair. Fortunately, my New York connection came to the rescue again, and introduced me to a skilled shipping company that specializes in shipping fine art and antiquities. These professionals were able to examine the sculpture and its shipping container, and then incorporate additional packing materials that allowed them to guarantee (with insurance) the delivery of my piece to its destination. Mission accomplished!

Planning ahead

A valuable (albeit expensive) lesson was learned: never take anything for granted. This applies not only to the design and construction of a piece of jewellery or object of art, but also to the assurance that it can survive being transported to and from its destination.

All’s well that ends well; the owl and the pussy-cat live to play another day. Perhaps I will need to create another piece to complete their story.

[19]Llyn L. Strelau is the owner of Jewels by Design in Calgary. Established in 1984, his by-appointment atelier specializes in custom jewellery design for local and international clientele. Strelau has received numerous design awards, including the American Gem Trade Association’s (AGTA’s) Spectrum Awards and De Beers’ Beyond Tradition—A Celebration of Canadian Craft. His work has also been published in Masters: Gemstones, Major Works by Leading Jewelers. Strelau can be reached via email at designer@jewelsbydesign.com[20].

[19]Llyn L. Strelau is the owner of Jewels by Design in Calgary. Established in 1984, his by-appointment atelier specializes in custom jewellery design for local and international clientele. Strelau has received numerous design awards, including the American Gem Trade Association’s (AGTA’s) Spectrum Awards and De Beers’ Beyond Tradition—A Celebration of Canadian Craft. His work has also been published in Masters: Gemstones, Major Works by Leading Jewelers. Strelau can be reached via email at designer@jewelsbydesign.com[20].

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Owl-and-the-Pussy-Cat-Owl-View.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Owl-and-the-Pussy-Cat-Pussycat-View.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/base.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/pearl2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/money.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/tree.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/case.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Boat_crop.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/owl-side-of-pearl.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/pussycat-side-of-pearl.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/8.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/7.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/9.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/6.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/JBD-Llyn-Strelau-Portrait-5-x-5.jpg

- designer@jewelsbydesign.com: mailto:designer@jewelsbydesign.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/bench-tips-feb-2019/

[9]

[9] [10]

[10] [11]

[11] [12]

[12] [13]

[13] [14]

[14] [15]

[15] [16]

[16] [17]

[17] [18]

[18]