Where Black lives don’t matter to jewellers

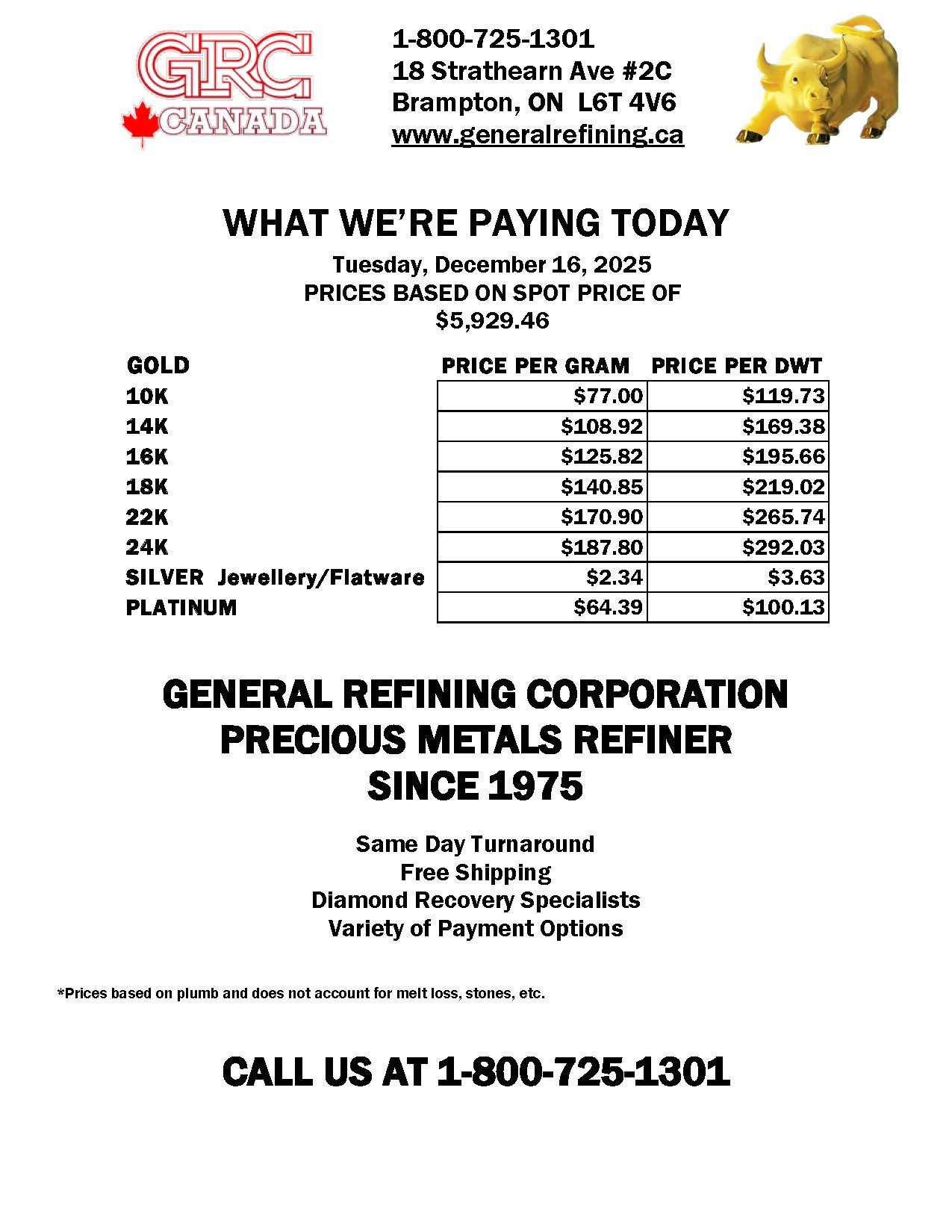

By Marc Choyt and Kyle Abraham Bi

Photo by Marc Choyt

After Alexia Connellan graduated from Columbia University with an art degree, the luxury-design jeweller worked as a professional photographer, and then as a project manager in the tech sector. However, a life-long love of rocks and gemstones eventually led her to the jeweller’s bench at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) and, ultimately, a career change.

When asked where she has felt racism in the industry, Connellan cites the 2016 American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) banquet dinner—an event where she received a Spectrum Award—as a particularly jarring moment.

“Someone turned to me and said, ‘Oh, I didn’t even know Black people could design jewellery!’” she says.

Most troubling, however, are the common harassments Connellan says she’s felt while working in the trade—particularly while pitching in jewellery stores.

“I’ll go into a jewellery store and be followed around by security, or not be allowed to try something on.”

These experiences are far from isolated incidents.

Robin Erfe works out of Brooklyn, designing pieces (primarily silver) out of a love for beauty and elegance. For Erfe, finding the resources to break into the trade has been a challenge. While many jewellers carry a family legacy, she does not.

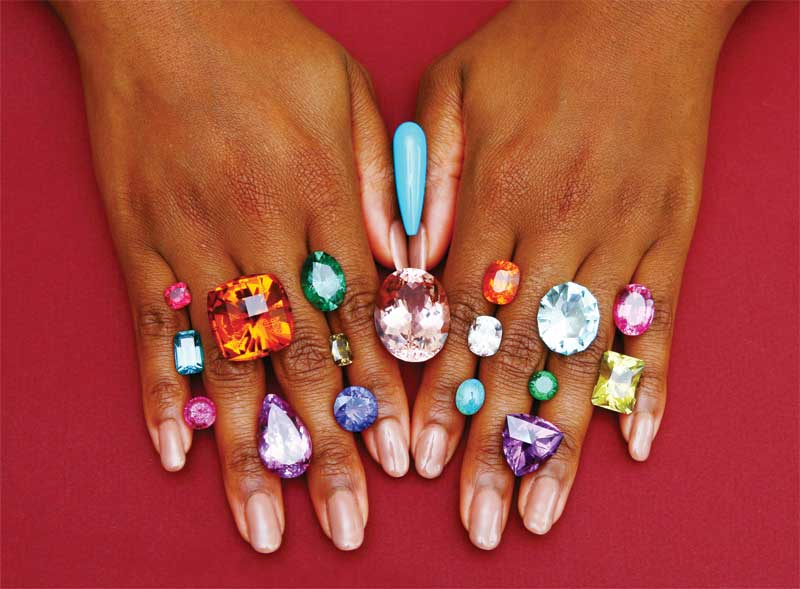

Photo courtesy DDI

Erfe is one of 29 Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour (BIPOC) U.S.- and U.K.-based jewellery professionals who, earlier this year, published an open letter to the industry inspired by the Black Lives Matters movement. Widely covered in trade and fashion publications, the letter serves as a call to action, addressing the overall lack of education and advancement opportunities for emerging designers.

Additionally, the letter emphasizes that, while the industry often appropriates and capitalizes on BIPOC culture, the voices of designers falling into this category are often underrepresented or missing altogether.

Connellan and Erfe agree these issues are hardly unique to the jewellery industry. Rather, they are reflective of broader structural inequalities within society—though, they add, there are concerns particular to jewellers.

Connellan was born in Jamaica, where she witnessed high cancer rates and the destruction of ecosystems due to mining.

When discussing how honest and open sourcing is central in the problem of sourcing gemstones, she doesn’t mince words.

“The rich foreigners take out the valuable goods, pay locals a nickel, go back to their country, and enjoy their spoils,” she says. “It makes a lot of people uncomfortable, but it’s the truth.”

Erfe (who describes herself as a ‘Black and Asian women who creates responsible and ethical jewellery’) also struggles to meld her core concerns for social and ecological justice in her business.

“I think it’s a fallacy, when it seems the only way to succeed in this industry is by hurting others,” she says.

Both women strongly support the responsible jewellery movement.

“‘Version one’ is better than ‘version none,’” Connellan says.

Uniting for a better future

Today’s jewellers widely recognize caring for the future is in their best interest—namely because millennials and gen-Z consumers tend to shop their values. Regardless of market trends, all of us want to leave a better world for our children and grandchildren.

Photo courtesy DDI

Perhaps the best place to get a ‘pre-COVID’ snapshot of where the industry is headed is the 2019 Chicago Responsible Jewellery Conference. The event saw a total of 44 speakers, including representatives from the Tanzania Women Miners Association (TAWOMA), Google, the U.S. State Department, the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC), Fairmined, IMPACT, Swarovski, and Columbia Gem House, as well as Chief Henrique Suruí from the Amazon and several small studio jewellers who are part of Ethical Metalsmiths.

The very makeup of the conference’s speakers and sponsors illustrates the best way forward is to work synergistically, bringing together diverse viewpoints to find market-based solutions for global problems.

Several standards for responsible and sustainable sources are being vertically integrated throughout much of the supply chain (RJC, Fairmined, Fairtrade, and Scientific Certification Systems [SCS] to name a few). Many of the most difficult challenges, however, remain in the small-scale mining sector, which has been a central focus of the ethical jewellery movement.

But how have the collective efforts to create a responsible and sustainable supply chain impacted small-scale miners (whose lives have largely been characterized by extreme poverty and exploitation)?

To answer this question, it’s helpful to have bit of historical context highlighting how hard and long some have been working to find solutions.

A brief overview of the ethical jewellery movement

While Oxfam and Earthwork’s ‘No Dirty Gold’ campaign may have started in 2004, these authors tie the ethical jewellery movement’s starting-off point to the release of Blood Diamond in 2006. While talking to retailers about ethical jewellery at industry shows like JCK Las Vegas was typically a non-starter in those days, that year also saw what was perhaps the first ‘fair trade jewellery’ meeting, sponsored by Martin Rapaport.

Rapaport’s efforts focused on bringing fair trade diamonds from small-scale miners in Sierra Leone, where another project was also being launched: the Diamond Development Initiative (DDI). It drew broad cross sector support, including from the United Nations (UN). In the situation briefing report Problems and Prospects, Ian Smillie framed DDI’s mission to create a fair trade diamond, referencing FLOCERT as a model. Smillie is currently chair of the DDI.

Then, in October 2007, a watershed Madison Dialogue meeting took place at the World Bank in Washington, D.C. Though comparable in make-up to the Chicago conference, only 100 were invited to attend.

That same year, The Tiffany & Co. Foundation funded Estelle Levin (now Levin Sources) to complete a study for TransFair USA (now Fairtrade USA), assessing the feasibility of Fairtrade certification for diamonds. It was found the developmental challenges of a Fairtrade diamond were formidable, but the market potential was huge.

Enter Fairtrade/Fairmined Gold in 2011. The events leading to the formation of this organization can be traced back to Greg Valerio, a jeweller from the United Kingdom who bought alluvial gold from Colombia’s Chaco region in 2004. The capacity-building expertise developed by Valerio’s initiative, the Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), was combined with the FLOCERT’s established certification system and global brand. (The two organizations ultimately split in 2013, when ARM signed a memorandum of understanding [MoU] with the RJC.)

Even before this time, some individuals had been pioneering other supply chain for years; most notably, stalwart Eric Braunwart of Columbia Gem House. More recent initiatives include the Tanzania Women Miners Association (TAWOMA), Moyo Gems, and Ruby Fair.

Fourteen years after Blood Diamond, arguably, kicked off an industry-wide conversation about ethical jewellery, it’s fair to ask: what has been the impact on the ground for Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour? This group supplies, as the BIPOC letter points out, the majority of our industry’s sourcing; their collective concern lies at the heart of the ethical sourcing community.

The numbers

Photo courtesy Robin Erfe

In context of Fairmined, there are 1470 workers in its ‘production system’ and 1680 ‘direct participants.’

Fairtrade mentions three mining sources: MACDESA (Minera Aurífera Cuatro de Enero Sociedad Anónima), Limata, and CECOMSAP (Central de Cooperativas Mineras de San Antonio de Poto de Ananea). Limata employs 43; MACDESA, perhaps 300 to 400—though these might be counted under Fairmined’s numbers as well.

Meanwhile, DDI’s Maendeleo Diamond Standards are implemented in 14 mining communities in Sierra Leone that Smillie says involve “a few thousand miners.” He estimates that, combined with De Beers’ GemFair initiative, which works with DDI, there might be between 6000 to 8000 participants.

Approximately 80 per cent of all coloured gems come from small-scale miners. These authors estimate the Fair trade-based initiatives might impact 5000 miners.

How many of the 120 million small-scale miners do these high-profile projects support? If we include broader communities impacted by the miners, we might come up with a number of around 25,000—a mere drop in the bucket.

Market failure

We must first start by acknowledging the difficulties of building capacity in post-colonial countries with weak civil society institutions.

People are not going to change unless they are certain of something better. Lebanon’s diamond mafia, traders who make 30 per cent margins on five-dollar grains of gold, and the ease of mercury to get gold out of dirt are just a few examples of things that can create dangerous headwind for any progress. Thus, it can take years to build trust in mining communities.

While pioneering projects have improved many lives, if ethical/responsible jewellery is measured within the context of its social and market impact in North America, it has been an utter failure.

The problem, however, does not lie with the market. In Canada and the United States, millions of millennials and gen-Zers want to align their purchases with their values, but these consumers are largely directed to options loudly marketed as ‘eco-responsible,’ such as recycled gold and lab-grown diamonds. (Neither one of these products address the sourcing concerns outlined in the BIPOC letter.)

Meanwhile, the market hasn’t even seen ‘fair trade’ branded diamonds from DDI, even though these stones are being purchased by De Beers. (Smillie told us he not did know the volume of diamonds being purchased.) Likewise, fair trade gemstones remain a niche offering, and certified Fairtrade and Fairmined gold are boutique options, offered only by a few small studios.

As such, millions of small-scale miners continue to live in extreme poverty and exploitation. Twenty million gold miners continue to dump mercury into their land and water. Millions of diamond diggers pocket only a few dollars a day and those who are part of producing ethical diamonds under the Maendeleo standards are not connected to a market which could drive the future growth on the ground.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed,” writer and activist, James Baldwin, said, “but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

A very short period

On July 8, 2000, The New York Times reported De Beers’ “artful image-building and brawny cartel management seemed threatened by association with these so-called blood diamonds.”19 Despite this, the article goes on to say, the company’s handling of conflict diamonds fell in its “favor” because it had “been able to distance itself in a very short period.”

In the framing of the Kimberley Process (KP), IMPACT (formerly Partnership Africa Canada), Global Witness, and others did not insist upon holding anyone in the diamond trade accountable for the estimated 3.7 million people killed in diamond-funded wars.

Ian Smillie, who was considered the ‘grandfather’ and ‘architect’ of KP, told these authors, “When we were negotiating the Kimberley Process, I knew if we spent too much time looking back, we’d never move forward.”

Certainly, those representing the small-scale miners believed the possibility of establishing a diamond certification system that prevented further bloodshed was worth the compromise of dropping any demand for restitution from those involved in the diamond trade who had funded the atrocities. It seemed, perhaps, the KP’s ratification brought with it a ‘never again’ commitment.

Photo by Marc Choyt

Of course, that Faustian bargain started to unravel in 2009 due to the industry’s lack of enforcement. Smillie dropped out, warning “jewellers have blood on them.” When Zimbabwe’s Marange diamond fields were certified ‘conflict free’ by the KP in 2011, Global Witness quit, but the decision was endorsed by the RJC.

These days, of course, we see it does not matter if the KP’s ineffectiveness is designed into its consensus-based model and narrow definition of ‘conflict.’ Indeed, the KP does not need to work in order to work.

‘Conflict-free diamond,’ as a marketing term, is more powerful than ever to the customers we sell diamonds to. Its narrative gives consumers peace of mind, independent of the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of the KP in context to human rights issues. Ultimately, one thing really matters in the diamond business: that diamonds sell, sell, sell.

This ‘conflict free’ argument is also central to the marketing of lab-grown diamonds, undermining prospects for programs that assist small-scale diamond miners for whom the KP was created to the market most interested in a natural fair trade diamond. Likewise, ‘ethical,’ ‘responsible,’ or ‘sustainable’ jewellers tend to market Canadian and De Beers Botswana product as ‘conflict free diamonds.’

Essentially, what happened in the past has become history to forget.

“The death of one man is a tragedy, while the death of a million is a statistic,” Stalin said.

Indeed: don’t think about the moms, dads, aunties, and child soldiers in those African villages who loved life, felt joy, and experienced heartbreak (just like George Floyd, his family, and so many others).

In his seminal 2014 article, “The Case For Reparations,” which was published in The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes of a “…strange and powerful belief that if you stab a Black person 10 times, the bleeding stops and the healing begins the moment the assailant drops the knife… There is this sense that if we ignore the issue, and don’t look, it will go away.”

Winners take all

In 2004—one year after the KP was established—the RJC was formed by De Beers, Rio Tinto, BHP Billiton, Cartier, Newmont Mining, Signet Group, Tiffany & Co, Zales Corp, Jewelers of America (JA), and a few others. Today, with its responsible sustainable standards, it has 1256 members and is, arguably, the voice of the industry.

In 2013, Earthworks, an environmental non-profit group, published a critique of the organization’s certification system, stating that, “the Responsible Jewellery Council system and its components are riddled with flaws and loopholes.” This sentiment was echoed by Human Rights Watch in 2018—the same year the first Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference took place, featuring keynote speaker and RJC board member, Mark Hanna.

Photo courtesy Alexia Connellan

Nonetheless, RJC membership jumped from 400 to more than 1100 between 2013 and 2018, affirming the jewellery sector does not necessarily see a conflict of interest in a certification agency that simultaneously functions, in the words of former RJC chief executive officer, Michael Rae, as ‘a trade association.’

The foundation of its standard is traceability and transparency; however, if a company owns a mine, this is an easy standard for it to achieve without ever changing its business model—for example, Rio Tinto can blow up indigenous sites and still be certified as ‘responsible’ under RJC standards.

In context to past activities, the RJC implanted its ‘grandfather clause’ in 2012, in which all previous materials from past mining were accepted within the current standard. This clause has gone largely unnoticed by jewellery professionals, as it is buried deep within the organization’s documents and has been left untouched by industry watchdogs.

Regardless, one pesky problem had remained for the RJC: small-scale BIPOC miners.

Beginning in 2013, when ARM signed its MoU with the RJC, BIPOC started appearing on the council’s homepage photos. It was a perfect match for the two groups: ARM received access to a huge funding network, while the RJC got a small-scale mining narrative it could use to show its concern for those hundred million plus small-scale miners.

In his 2018 book, Winners Take All, Anand Giridharadas describes what is taking place, detailing the ways the rich and powerful rebrand themselves as the saviours of the poor without ever having to sacrifice anything meaningful for the common good. Change, he writes, is permitted as long as it does not change the underlying system; unfettered atrocities from the past are justified by current benevolence.

As Audre Lorde famously said, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Missing the mark

“The industry knows what’s happening and it keeps slapping on what feels comfortable,” Erfe says, exasperated. “I don’t know what to do to keep hopeful. The only thing I can tell people is everything is interconnected.”

Indeed, the ethical sourcing movement is a complex system: companies create narratives to hide their self-interests (which, sometimes, can only be determined after years of observations), while participants double down on unspoken agreements.

Most jewellers are united in wanting a better world. As such, we should be allies—especially because protecting our industry seems to simultaneously bolster our economic interest.

“This is not an industry where dissent is encouraged,” a speaker at the Chicago conference told this article’s authors. This individual, who has attended conferences, industry summits, and consults with Ethical Metalsmiths, did not want to be named.

“The Chicago conference is not an industry initiative,” they said, but rather “born out of [studio jeweller] Susan Wheeler’s desire to make the world a better place.”

Photo by Marc Choyt

In the United Kingdom, where jewellers are largely catalysts for change, there are more than 250 Fairtrade Gold-certified jewellers. While the notion of ‘recycled gold’ is far from accepted as an ethical choice in that country, this material typically tops North American supply houses with the broad support of ethical jewellers.

Meanwhile, the gold trade continues just as it always has: billions of dollars of gold—about 20 per cent from small-scale miners, using mercury to refine—is smuggled out of African countries to Dubai. Much of it comes from countries with lax human rights codes or ones that use the metal to fund hostilities (read: blood gold, conflict gold). From Dubai, the gold ends up in Switzerland—the country where 70 per cent of the world’s gold is refined.

RJC-certified Swiss refiner Valcambi is the world’s largest gold supplier. Earlier this year, however, Global Witness published a study, implicating Valcambi for importing conflict gold from small-scale miners in Sudan.

So it is: big miners launder gold through corrupt refineries in Africa. The product enters Switzerland under an RJC-certified supplier and, miraculously, it comes out the other side as Swiss ‘Better Gold’—yet no one can identify from where the gold came.

In the fall of 2019, Valcambi purchased exclusivity to the Fairtrade-certified MACDESA mining site, which put supplier CRED Sources out of business (the small company had been supplying jewellers with Fairtrade gold at the same price as certified recycled gold—seven per cent over spot). Fairtrade itself supported the Swiss monopoly by not re-certifying Sotrami, another Peruvian volume mining source CRED could have used to bring in affordable Fairtrade gold. Instead, with Fairmined/Fairtrade distribution mainly controlled by RJC members and selling at plus 20 per cent or more, what we have is zero mass market opportunity.

When a jeweller pitches recycled gold as ‘eco-friendly’ and ‘ethical,’ they reinforce a narrative that undermines those boutique jewellers selling certified small-scale mining gold to consumers who want to be part of the solution.

On the ground, small-scale miners get 70 per cent of spot price for their gold and are loaned money to cash flow their business at 20 per cent monthly interest. Thus, 20 million small-scale gold miners in Africa are essentially economic slaves to poverty and exploitation.

Where Black lives don’t matter

In the article cited above, Ta-Nehisi Coates details the economics of missed opportunities due to Jim Crow policies within societal structures—a situation that has parallels to the poverty cycle in post-colonial countries where resources have become resource curses.

“We believe white dominance to be a fact of the inert past, a delinquent debt that can be made to disappear if only we don’t look,” he writes.

“The urge to use the moral force of the Black struggle to address broader inequalities originates in both compassion and pragmatism. But it makes for ambiguous policy.”

In the BIPOC letter addressed to the industry, two of its 15 points mentioned sourcing—yet this issue and that of education/advancement opportunities are facets of the same structural reality.

Millennial and gen-Z consumers may be misdirected by recycled gold, but this illusion cannot hold forever. Lab-grown diamonds are eating into the mined diamond market largely due to their ‘ethical’ halo—and if there’s one sure way to affect change, it’s through the wallet.

To create a new cut, we need to work beyond business angles, and call out power and racism in all its insidious forms. We need to insist upon supply chains that support social and economic justice for BIPOC people both in our country and around the world.

The fact that even jewellers who profess concerns for the BIPOC community do not yet demand certified gold from small-scale miners at plus seven per cent over spot from their RJC sponsors who could provide it suggests BIPOC lives don’t matter.

In the history and ongoing use of the term ‘conflict-free diamonds,’ and the lack of truth, reconciliation, and restitution, Black African lives don’t matter; the term should be torn down like confederate monuments of generals.

Yet, within transformational energy of the Black Lives Matter movement, the BIPOC letter is an opportunity to find a new story; indeed, it is a call for both healing, action, and collectivism from the deep well of our common humanity.

Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry, a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds, is available online, at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifesto or by email at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry, a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds, is available online, at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifesto or by email at marc@reflectivejewelry.com.

Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram) is the brand catalyst at Reflective Jewelry. His duties include brand management, online marketing, and SEO, as well as writing, editing, and conducting research on issues related to fair trade and ethical jewellery. Abram can be reached by email at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com or on LinkedIn.

Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram) is the brand catalyst at Reflective Jewelry. His duties include brand management, online marketing, and SEO, as well as writing, editing, and conducting research on issues related to fair trade and ethical jewellery. Abram can be reached by email at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com or on LinkedIn.

Columnists’ opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Jewellery Business.