Blockchain and the road to ethics

by Samantha Ashenhurst | December 5, 2022 12:52 pm

By Kyle Abraham Bi and Marc Choyt

[1]

[1]Illustration by Alyssa Lown (alyssathefriend.com[2])

In recent years, evolving consumer demands and concerns over ‘conflict’ diamonds and minerals have coincided with the emergence of a powerful data-tracking approach known as ‘blockchain.’ This technology, in development since the 1980s, anchors a core tenant of ethical sourcing: traceability and transparency.

Everyone involved in ethical sourcing recognizes the need to trace our materials from mine to market, and blockchain promises to enhance our abilities to do so. The plans of some multinational mining conglomerates and major retailers to incorporate blockchain have recently been accelerated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, leading some in the industry to herald a ‘paradigm shift.’[3]

For such multinational diamond- and/or gold-mining conglomerates, as well as laboratory-grown diamond manufacturers, blockchain is ideal. They control the mine-to-market pipeline and, from there, can demonstrate to the consumer all their responsible efforts[4].

Yet, with anything new, there are winners and losers.

Traceability and transparency: A means to what end?

Let’s be clear about one thing: blockchain does not necessarily involve any change in how a supply chain functions. Rather, it enhances and magnifies the structures already in place.

Pre-dating blockchain technology, large-scale mining (LSM) operations made traceability and transparency relatively straightforward. If De Beers, for example, owns and controls a diamond from the time it is mined to the time it is sold to a third party, this 134-year-old behemoth should, in theory, be able to share with this third party every conceivable detail about the stone’s origin.

It has not done so simply because this is not the interest of their brand. Perhaps there are diamonds from the ‘80s and ‘90s still sitting around in the company’s London offices, which have been ‘grandfathered in’ to its ‘responsible’ standard. Some of these diamonds may have funded the wars that killed 3.7 million people back when De Beers still controlled[5] upwards of 90 per cent of the supply chain.

Even without acknowledging that blockchain bypasses historical atrocities, does knowing a particular diamond comes from a specific site offer the consumer—who generally has only a superficial understanding of sourcing issues—assurance of ethical provenance?

What about diamonds transparently traceable to Zimbabwe, for example, where mining has been known to involve forced labour? Not to mention that many multinationals certified under the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) may enforce traceability and transparency in one supply chain while committing atrocities[6] in another. Does working with these companies help or hinder the future development of ethics in our industry?

Traceability and transparency do not provide a qualitative judgment of what is being assessed. Equally concerning, this bypasses parts of our supply chain that ought to be a major focus for our concern.

The forgotten voices of ASM

“Please think of me. I am very hungry.”

These were the words of a small-scale gold miner working in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in October 2021. He was one of a very few workers who spoke English, but no interpreter was needed to comprehend the mirrored expressions of his several-hundred companions. The desperation was unmistakable.

While many LSM operations have the groundwork and infrastructure in place to foster improvements in traceability and transparency and satisfy the demands of Western consumers, the vast majority of artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) operations do not.

Small-scale gold miners are the world’s No. 1 source of global mercury contamination[7]. Small-scale diamond miners are (outside of Alrosa[8]) the top source for blood diamonds. Across contexts, they represent those most in need of the capacity building and support our industry can provide.

For these miners, creating an ethical supply chain will never be as simple as entering a data point in a blockchain-powered spreadsheet. It will not be simple at all, judging by the fact that, out of 100 million working in ASM[9], perhaps less than 20,000 have benefitted[10] from the ‘ethical’ solutions the jewellery world has mustered in the past 10 years.

Given our industry’s inability to address endemic poverty and exploitation of small-scale mining through market forces, blockchain becomes another brick in the wall for a two-tiered system of precious metal and gemstone sourcing, sending the massive informal swaths of these industries even further underground.

‘Underground’ means, of course, ‘out of sight,’ so we might ignore feelings of common humanity with the miner who is hungry—the miner who, at the end of 10 hours of digging in the dirt, is frying plantains in the same pan used earlier to burn out the mercury from his two dollars’ worth of gold.

Indeed, the fact this is how a large portion of our gold is sourced today is a sad indictment for our industry, which is in the business of creating talismanic symbols of love and connection in the world.

Searching for creative solutions

In context to the larger ethical jewellery movement, there has been an underlying battle regarding the definition of ‘ethics’ and ‘responsible sourcing.’ There are those who would make traceability and transparency and blockchain the bull’s eye of ethical sourcing, and others—including the writers of this article—who say it is foundational, but not sufficient.

From a business point of view, what matters most is how the market is defined. Brilliant Earth[11], the self-proclaimed “global leader of ethically sourced fine jewellery,” largely dominates the web for anything related to ethics and jewellery. The company has more power to shape ethical narratives reaching the consumer than any other. In addition to recycled gold—and, until this past March, diamonds from Alrosa—it now offers ‘blockchain diamonds’ for sale on its site. This gold and these diamonds, however, primarily keep current supply structures in place.

The issue for us (whose company, Reflective Jewelry, has been involved in the ethical jewellery movement for 17 years) has been: how do we get jewellers to care and act, and offer more than lip service in the effort to create supply chains which support strong and sustainable local economies for producer communities? Such efforts could free millions from exploitation and extreme poverty.

The challenges are many, but it starts with a circle of fair and equitable relationships. The consumer market is there, particularly in North America. These are people who want to help. They want connection between purchases and values. The industry, however, has managed to create market narratives which divert the energy for change.

Consumers need to understand the linkages between small-scale mining, local economy, and regenerative economic models. Traceability and transparency-centred narratives enhanced by the powerful voices of large retailers and multinationals—narratives which are further magnified by blockchain—undermine the potential of a market which could be a true catalyst for change.

For all the talk about ethical sourcing and the massive demand by millennials and gen-Z customers who want to use their money to make the world a better place, there has been little meaningful change in how we source our gold or gems.

In the words of the great Leonard Cohen:

Everybody knows the deal is rotten.

Old Black Joe’s still pickin’ cotton

For your ribbons and bows,

And everybody knows.

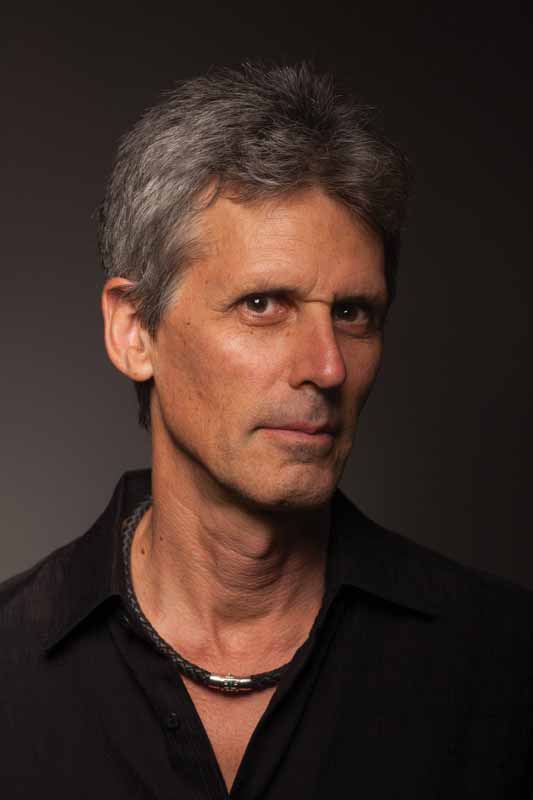

[12]Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry[13], a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States[14]. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds[15], is available online, at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifesto or at marc@reflectivejewelry.com[16].

[12]Marc Choyt is a regular contributor to Jewellery Business, focusing on ethical jewellery issues. He is president of Reflective Jewelry[13], a designer jewellery company founded in 1995. He pioneered the ethical sourcing movement in North America and is also the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States[14]. Choyt’s company was named Santa Fe New Mexico’s Green Business of the Year in 2019, and he has been honoured with several awards for his efforts to support ethical jewellery. His e-book, Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds[15], is available online, at reflectivejewelry.com. Choyt can be reached on Twitter at @Circlemanifesto or at marc@reflectivejewelry.com[16].

[17]Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry brand catalyst since 2017, has functioned as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project[18] and appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference[19]. He holds multiple roles with Ethical Metalsmiths, serving on its Advisory Council and Action Coalition and as an editor/author for its blog, The Source[20]. He is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition[21] x GIA Distance Education Scholarship, and a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry[22]. Abram holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com[23].

[17]Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry brand catalyst since 2017, has functioned as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project[18] and appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference[19]. He holds multiple roles with Ethical Metalsmiths, serving on its Advisory Council and Action Coalition and as an editor/author for its blog, The Source[20]. He is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition[21] x GIA Distance Education Scholarship, and a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry[22]. Abram holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com[23].

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/opener_Bypassing-Lead-image.jpg

- alyssathefriend.com: https://www.alyssathefriend.com/

- leading some in the industry to herald a ‘paradigm shift.’: https://cointelegraph.com/news/blockchains-are-forever-dlt-makes-diamond-industry-more-transparent

- all their responsible efforts: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/ethics-august-2022

- De Beers still controlled: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/cons-products/fashion-/-cosmetics-/-jewellery/de-beers-fighting-to-restore-monopoly-challenges-lie-ahead/articleshow/19154196.cms?from=mdr

- while committing atrocities: https://londonminingnetwork.org/2021/08/rio-tinto-commits-to-assessment-of-panguna-mine-legacy/?mc_cid=cf30efadcf&mc_eid=7ec8e29366

- No. 1 source of global mercury contamination: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5969110

- outside of Alrosa: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5969110

- out of 100 million working in ASM: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/extractiveindustries/brief/artisanal-and-small-scale-mining

- less than 20,000 have benefitted: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/bipoc-jewellers

- Brilliant Earth: https://reflectivejewelry.com/news/brilliant-earth-review

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Marc-Choyt-portrait.jpg

- Reflective Jewelry: https://reflectivejewelry.com

- the only certified Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States: https://reflectivejewelry.com/ethical-sources/fairtrade-gold

- Ethical Jewelry Exposé: Lies, Damn Lies and Conflict Free Diamonds: https://reflectivejewelry.com/ethical-jewelry-expos%C3%A9

- marc@reflectivejewelry.com: mailto:marc@reflectivejewelry.com

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Abram_headshot.jpg

- USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project: https://www.land-links.org/project/zahabu-safi-commercially-viable-conflict-free-gold-project-cvcfg/#project-content

- Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference: https://www.chiresponsiblejewelryconference.com

- The Source: https://ethicalmetalsmiths.org/blog-the-source

- Black in Jewelry Coalition: https://blackinjewelry.org

- 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry: https://bipocopenletter.com/open-letter

- kyle@reflectivejewelry.com: mailto:kyle@reflectivejewelry.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/blockchain-and-the-road-to-ethics/