Carbon copy: When imitation isn’t the highest form of flattery

by charlene_voisin | February 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Jacquie De Almeida

[1]

[1]

Shelly Purdy remembers the first time she realized her designs had been copied.

It was early on in her career and a friend had pointed out an advertisement for rings that bore a striking resemblance to her own.

Surprised and disappointed, Purdy had no choice but to move on, feeling there was little she could do about it.

“You can’t stop someone from copying your work, and there’s no use in getting a lawyer,” says the Toronto-based designer. “It’s cost-prohibitive, especially if you’re an artist and you’re coming up with new designs all the time and that’s all you do.”

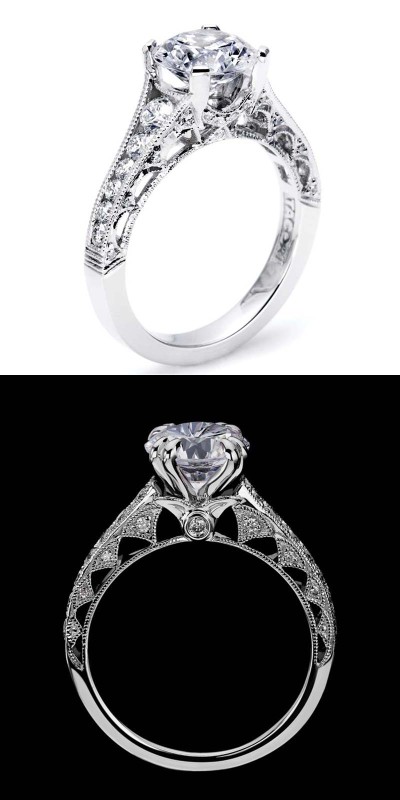

Copyright and trademark infringement cases are rife in industry headlines. In 2011, the high-profile showdown between wedding ring manufacturers Tacori and Scott Kay eventually resulted in both sides dropping their claim and counterclaim, and a California judge dismissing the case with prejudice. The outcome came several months after Tacori sought and lost a preliminary injunction against Scott Kay over its ‘Heaven’s Gates’ collection, alleging it infringed on its ‘reverse crescent’ copyrights. In the end, although Tacori president Paul Tacorian said he disagreed with the court’s view, he decided to drop the lawsuit after re-evaluating the company’s legal position. The battle cost millions.

Closer to home, Canadian jewellery manufacturer JewelPops sued both U.S.-based Royal Chain and Helzberg Diamonds, claiming the companies infringed on its copyrights and trademark for its Kameleon collection designs. Both cases were later settled.

While Purdy’s predicament was not on the scale of either case, it’s the type of thing that happens every day in the jewellery industry to varying degrees. It’s also a constant source of aggravation and one which some designers say ‘comes with the territory,’ even though copyright exists automatically when an original work is created.

A tangled web

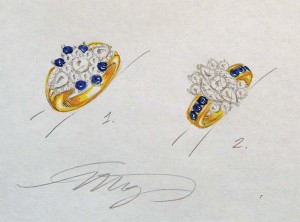

[2]

[2]In pre-Internet days, designers guarded their work, showing their catalogues only to potential clients, but that’s all changed. The ease with which a consumer can find just about any design they want simply by doing a Google image search has added to the problem. If someone doesn’t want to shell out top dollar for a brand name, a click of the mouse can give them what they’re looking for.

Peter Myerson, president of custom design firm, Myerson’s Ltd., says his company is often approached to re-create a ring a consumer has taken off the Internet. In many cases, they have no idea whose design it is.

“Our policy in these cases is to design a variation of what we see,” says Myerson, who also sits on Jewellers Vigilance Canada’s (JVC’s) board. “I don’t like to be a copycat, and I think in the trade, it’s not at all unusual for [copying] to happen. The very popular brand names are being reproduced within the trade as so-called custom designs.”

He says larger-scale copying is more common in the United States, and so are the lawsuits. “We don’t have that volume here and don’t have the wherewithal to produce those numbers,” he added. “What you’re going to see is onesies and twosies.”

Myerson says the ease of designing in-house at the retail level contributes to the problem, although in most cases, the intent is not to steal a design. Consumers often point out aspects of a particular design they like, hoping to have them incorporated into their own piece. “I think when you’re making one-offs, it’s an extra aid in coming up with another design.”

[3]

[3]No doubt, copying can be frustrating, given the time and effort that goes into designing a piece of jewellery and the cost of taking legal action. Myerson says he’s seen his designs ‘walk,’ meaning a sketch he’s drawn up for one retailer ends up in the hands of another who then calls him for a quote to produce the piece. He’s also had a retailer give a consumer one of his designs only to have them take it to another jeweller to produce at a lower cost.

“We recommend that a design we’ve created for a retailer not leave the store, but not everybody does that”¦I’ve seen this happen over and over again,” says Myerson. “There’s nothing I can do about it but get a little aggravated. And I’ve had it happen so often that I don’t get aggravated anymore. I wouldn’t call it being a copycat. I would say it’s someone taking advantage of a situation.”

However, Myerson has also experienced the problem on a larger and more serious scale. An ongoing contract to create hundreds of cufflinks and bracelets annually for a corporate client suddenly dried up after a few years with no explanation. It wasn’t until a piece came in for repair one day that he got his answer. Sure enough, it was his design, but he didn’t make it. He later found out a new purchaser had taken the designs to a less expensive manufacturer who made a mould, but neglected to remove Myerson’s hallmark. He estimates at least 500 cufflinks were produced this way. “We actually got a lawyer involved,” he said. The client’s deep pockets and resources, however, made pursuing legal action too costly.

Laying down the law

[4]

[4]Intellectual property lawyer Gary Daniel with Blake, Cassels & Graydon LLP in Toronto says the law doesn’t classify copying a design as counterfeit, but rather infringing. “Counterfeit is where somebody is both slavishly copying something and trying to mislead the consumer into believing the product comes from the original source.”

He acknowledges weighing the costs of taking legal action is a definite concern, but adds having a lawyer send a demand letter is sometimes enough to get people to stop what they’re doing or risk an expensive lawsuit.

Still, he says in a one-off or custom-design situation where there is copyright infringement, taking legal action can benefit the designer to some extent.

“Sometimes it’s worth [suing] to send a message to the community that you will enforce your copyright,” Daniel says. “The amount you spend may be greater than the amount that is at risk. Also, although you will never know how much it saves you by someone deciding to not copy your design, I think it’s important to remember that you do have copyright in your design and you want to be known as a person who monitors the marketplace and will take appropriate action. I think if you take a long-term view, it is potentially an effective strategy.”

JVC executive director Phyllis Richard says few complaints have been made to the organization, and points to the fact people have to defend their own intellectual property rights as a possible explanation.”¨ If a complaint were laid, Richard says JVC would treat it as any other and follow up with the designer allegedly copying another’s work.

“We would ask them for an explanation, but we cannot enforce the law. Like in consumer complaints, sometimes we get responses and sometimes we don’t, but we would certainly [look into it].”

Richard says that although JVC’s code of ethics doesn’t specifically mention copyright infringement, it does state members “shall be cognizant of and conduct themselves according to the laws of Canada and any other country in which they do business.” With the apparent pervasiveness of the problem, however, she notes perhaps greater attention ought to be drawn to it.

“It would be worth exploring how to make copyright infringement stand out more so that industry members recognize that copying somebody else’s work is against JVC’s code of ethics,” she said.

Although the prevalent attitude is still one of acceptance, Canadian designer Hera Arkarakas says she takes steps to minimize the damage. In addition to trademarking her logo, Arkarakas says her first line of defence is to create an entire collection, rather than simply a few pieces. Branding is also critical. The combination, she says, brings prestige to a line and creates a ‘designer philosophy’ that retailers can appreciate.

“You’re always going to have someone who is making something similar to what you’re doing, but if a prominent retailer wants to carry a brand or a designer’s look, you’re hoping they’re going to go with you because you have a whole collection as opposed to one piece knocked off here and there,” Arkarakas says.

The other part of the equation is ensuring quality, which in the case of most knock-offs, is quite low. Pieces are also usually lighter to keep prices down.

“A retailer might be able to get one of my rings or necklaces from a Joe Schmo manufacturer that’s knocked it off, but I protect myself with a whole collection with our standard of quality and attention to detail,” she says. “It might look like mine, but take a good look at it.”

A code of honour

[5]

[5]Engagement rings tend to be copied most often, Purdy says. They are usually the first important piece of jewellery a consumer buys, and the one they’ll be looking to pick up for the least amount of money. While she agrees branding can help protect against copying to a certain extent, part of the answer lies within the industry itself.

“I think some jewellery designers do have a code of honour—the ones that have their own looks and style and work toward branding,” she says. “These are the inspired and creative ones. Their priority is to make their artistic marks. The lowest price, fast sale, and an attitude of being able to custom-make virtually any ring design turns it into a commodity.”

Steve Parker, owner of Customgold Manufacturing Ltd., in Vancouver, agrees copying is widespread but adds a formal code of honour would have little meaning.

“There is always an element in our industry that will do anything for money,” he explains.

Parker says his work and those of his design team have been copied, and while his reaction was partly one of being flattered to a certain extent, he is quick to point out the piece was of lesser quality. Like Myerson, he’s seen his designs walk many times, only to have the client unhappy with the results and asking Parker to create the piece himself. He sees it as karma.

“I think the marketplace sorts those things out,” he says. “In the end, I think it comes around. The customer doesn’t like the piece and the one who produced it loses a client.”

To better protect itself and its clients, Customgold uses a log-in feature on its website, preventing others from viewing designs.

“By doing this, those who support us and invest in our designs don’t need to worry about an unscrupulous competitor ‘stealing their sale’ by simply copying [a piece] from our website,” he adds.

Yet, in an industry that promotes itself as artistic and innovative, does the prevalence of copying diminish that? Parker doesn’t think so.

“I think there are great designers and great leaders in design, but that doesn’t necessarily mean every goldsmith out there is a great designer,” he explains. “They might just be able to construct the product and need to look elsewhere for designs, and unfortunately, that’s often someone else’s work.”

Is there a point where enough is enough?

“If someone directly copied my designs to the ‘T’ with quality etc., and with my hallmark, that would be the breaking point and I would consider taking legal action,” Arkarakas adds.

Aside from the costs of pursuing a copyright infringement case, the fact is, by the time it gets to court, trends may have changed and the design may not be as relevant as it once was. Yet, the time and effort that goes into creating an original design can be substantial, making copying a bee that stings nonetheless.

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/carbon_copy.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/bigstock-Keyboard-Key-With-Copyright-S-1831520.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Photo-8.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/HeavensGatestacori-ring.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/bigstock-Scales-Of-Justice-Atop-Legal-B-28912463.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/carbon-copy-when-imitation-isnt-the-highest-form-of-flattery/