Chameleon diamonds: How heat and darkness bring out the best in these colour-changing stones

by charlene_voisin | February 1, 2015 9:00 am

By Branko Deljanin

[1]

[1]Chameleon diamonds have an unusual ability to change colour temporarily, either when gently heated to approximately 150 C (thermochromism) or after prolonged storage in the dark (photochroism). The stable colour shown by chameleon diamonds is typically greyish-yellowish-green to greyish-greenish-yellow (i.e. olive), whereas the unstable hue is generally a more intense brownish or orangey-yellow to yellow. After heating, a chameleon diamond quickly returns to its original colour. The change in colour after storage in the dark is usually not as dramatic as that seen with heating, and for some members of the trade, a temporary photochromic colour change must be present for a diamond to be referred to as ‘chameleon.’

When these rare stones are certified by a reputable lab, they generally command a premium over coloured diamonds exhibiting the same colour, but without the ‘chameleon effect.’

According to some sources, diamond broker Peter K. Kaplan is generally considered to be the first person to note the wonder of chameleon diamonds when in 1943, he observed a stone change colour after it was placed on a very hot polishing wheel. The diamond’s owner had also noticed the light yellow-green stone turn dark green after storing it in a jewellery box. Not knowing what she had was a highly valuable diamond likely worth a lot more than the relatively small amount she paid, she sought to return it, believing its ability to change colour was a defect. Over the years, chameleon diamonds have been the subject of a great deal of study (including research by this article’s author and an international team of gemmologists) to determine how they change colour.*

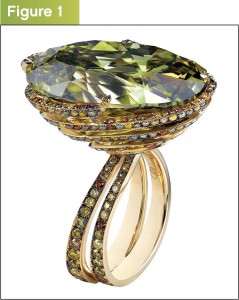

Chameleon diamonds are a truly exclusive gift of nature. The largest found to date weighs 31.32 carats (Figure 1, page 2), although one of the most beautiful chameleon diamonds is a stunning 8.04-carat radiant-cut stone graded by Gemological Institute of America (GIA) as a fancy dark grey-green chameleon. Due to colour rarity and size, this diamond is valued at $2.1 million US. And back in 2011, Christie’s Hong Kong auctioned off an 8.80-carat chameleon diamond ring for $590,000 US.

Chameleon characteristics

[2]Chameleon diamonds do not appear in all colour hues and cannot be found in intense and vivid colours. However, the colour combinations always include the following: green, yellow, brown, and grey. Further, they most often contain at least two overtone colours, such as ‘greyish-yellowish-green.’ It is rare for a chameleon diamond to have only one pure hue, although some are categorized as ‘light to fancy light yellow,’ becoming greenish-yellow after heating (i.e. one degree more intense).

[2]Chameleon diamonds do not appear in all colour hues and cannot be found in intense and vivid colours. However, the colour combinations always include the following: green, yellow, brown, and grey. Further, they most often contain at least two overtone colours, such as ‘greyish-yellowish-green.’ It is rare for a chameleon diamond to have only one pure hue, although some are categorized as ‘light to fancy light yellow,’ becoming greenish-yellow after heating (i.e. one degree more intense).

Colour description

For years, GIA included “Known in the trade as chameleon diamond” on its reports for only those stones exhibiting a ‘green’ or ‘greenish’ component; chameleons that were a mixture of yellow, brown, and grey did not receive this distinction on reports.

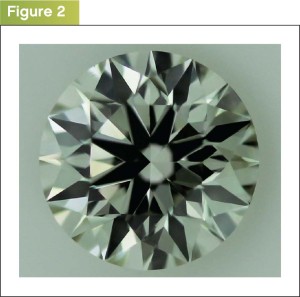

More recently, however, we have seen reports in the Canadian market for stones graded as ‘fancy grey’ that received the chameleon designation (Figure 2, page 3). This suggests temporary colour change is more important than the actual colour in daylight, and corroborates findings reported in a 2005 article (Hainschwang et al.) that even diamonds lacking a green component can be called chameleon.

Based on our research, we propose that two different stable colour groups can be observed in chameleon diamonds:

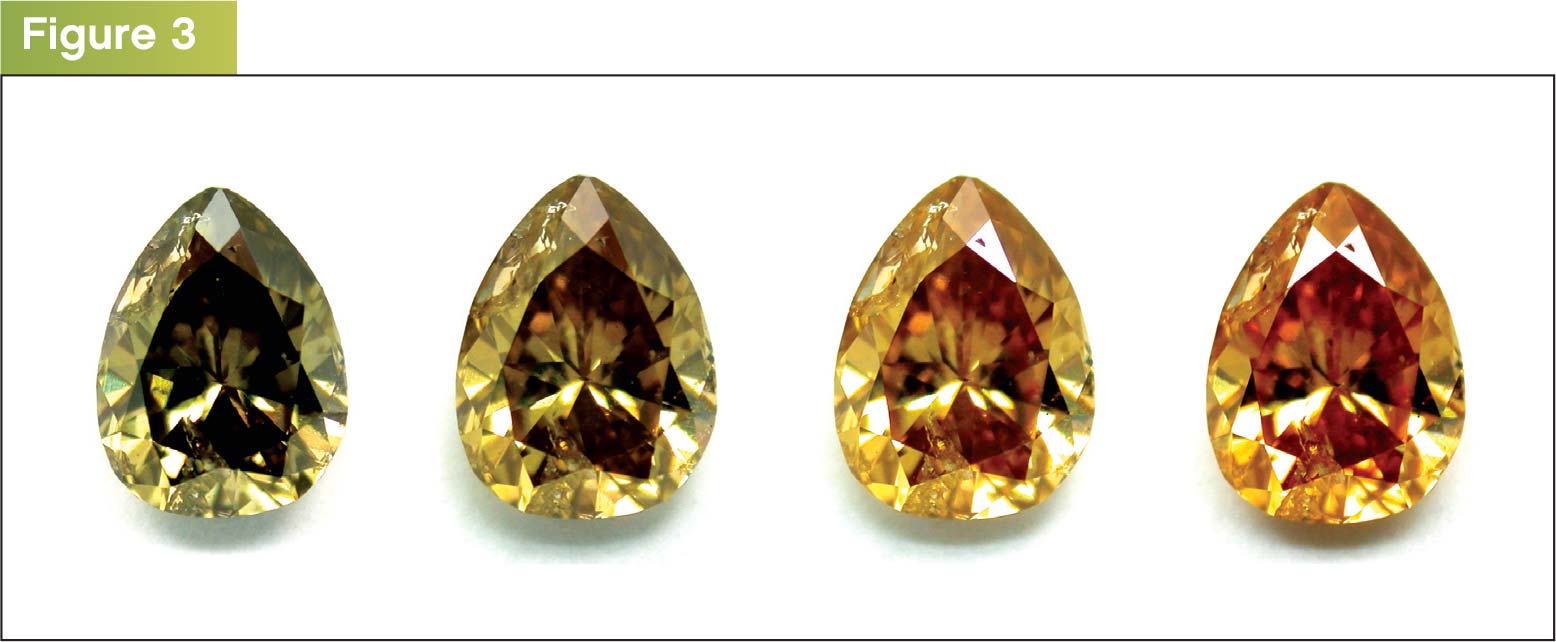

- Green with a grey, brown, or yellow colour component (‘olive’); or yellow with green, brown, or grey modifying colours. Both these groups exhibit green-to-yellow behaviour with heating or after prolonged storage in the dark. This colour change is commonly associated with chameleon diamonds, and as such, they are referred to as ‘classic chameleons’ (Figure 3, page 4).

- Light yellow to yellow, with typically a greenish, greyish, or brownish component. These are referred to as ‘reverse chameleons,’ as they lack a photochromic colour change—that is, they become slightly yellower and more saturated only when heated.

Similar to all fancy coloured diamonds, no two chameleons are exactly alike and many colour combinations are found.

Colour origin

[3]

[3]Chameleon diamonds are classified as having natural colour, as their behaviour cannot be duplicated and there is no known treatment to cause the chameleon effect in other stones. This phenomenon is not a ‘colour shift’ that can be observed when a yellow diamond with strong green-yellow fluorescence appears more green under fluorescent light (and daylight with ultraviolet [UV]). Many treated green-yellow diamonds (i.e. neon) colour-shift from more yellow to more green when the colour centre (caused by irradiation and HPHT treatment) in the green part of the visible spectra (503nm) is triggered by fluorescent light.

Shapes and sizes

As mentioned, chameleon diamonds comprise a small percentage of the coloured diamond group. The larger the chameleon diamond, the more dramatic the colour change. Similar to most coloured diamonds, chameleons are usually cut into fancy shapes like princess, emerald, oval, radiant, marquise, and pear, rather than round brilliant.

Reaction to UV radiation

Based on the findings of our testing, there are basically two types of responses to UV radiation:

- Classic group: strong chalky-yellow to chalky-orangey-yellow under long-wave and one degree weaker under short-wave UV.

- Reverse group: strong chalky-blue to blue under long-wave, and weaker chalky-blue to yellow under short-wave UV.

Â

Spectroscopy

Hydrogen was identified in all samples by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) (3107cm-1 peak). We determined most chameleons are Type IaA diamonds. Some minor nickel-related emissions were detected by photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy in most of the samples.

Explaining the ‘chameleon’ phenomenon

[4]

[4]The presence of hydrogen and nickel in chameleon diamonds has been demonstrated by various spectroscopic methods—emissions assigned to nickel impurities were identified by PL spectroscopy, particularly in the classic group. At present, we can only speculate these two impurities are the cause of the colour change exhibited by classic chameleon diamonds.

The results point to a defect involving hydrogen that could be detected with an infrared spectrometer combined with the 480nm band (related to isolated single nitrogen atoms) detected using a visible spectrometer.

This combination seems to cause the thermochromic and photochromic change in colour, but whether or not nickel plays a role in colour change remains to be seen. In the diamonds exhibiting only a thermochromic colour change (i.e. reverse chameleons), the defects appear to be solely hydrogen-related.

Sources of chameleon diamonds

It is difficult to definitively prove the origin of chameleon diamonds based on testing, but mines located in the Central African Republic produce a good percentage of classic chameleons, while Rio Tinto’s Argyle may be one source of reverse chameleons, which are rich in hydrogen.

Testing for chameleon diamonds

[5]

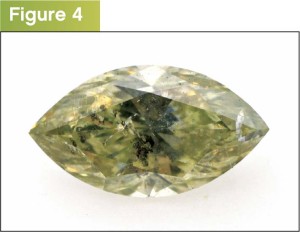

[5]The characteristic ‘olive’ colour of chameleon diamonds may be deceiving. Our lab recently tested a 1.12-carat fancy greyish-greenish-yellow (‘olive’) diamond of I1 clarity and with typical strong orangey-yellow fluorescence similar to what chameleon diamonds can exhibit (Figure 4). However, this stone did not change colour when heated.

The following are simple ways for a jeweller or gemmologist to recognize classic chameleon diamonds:

- Visually inspect the diamond for a greenish colour modifier.

- Look for strong orangey-yellow fluorescence under long-wave UV light.

- Check for phosphorescence (i.e. a weak to medium greenish-yellow colour when short-wave UV light is removed).

Only when all these initial criteria are satisfied should the stone be gently heated on a hot plate to observe the colour changing from green (ish) to more orangey-yellow. (Note: If using a lighter, keep the diamond in motion over the flame. This test is not recommended for stones that are more green than yellow.) If the diamond is a chameleon, it will revert to its original body colour within a couple of seconds. (Place it on white paper to better observe the colour change.) It is advisable to send any natural olive-colour diamonds to a laboratory to confirm by advanced testing whether they are chameleon, as heat may change the colour of a non-chameleon green diamond permanently.

Chameleon diamonds in the Canadian and U.S. markets

[6]

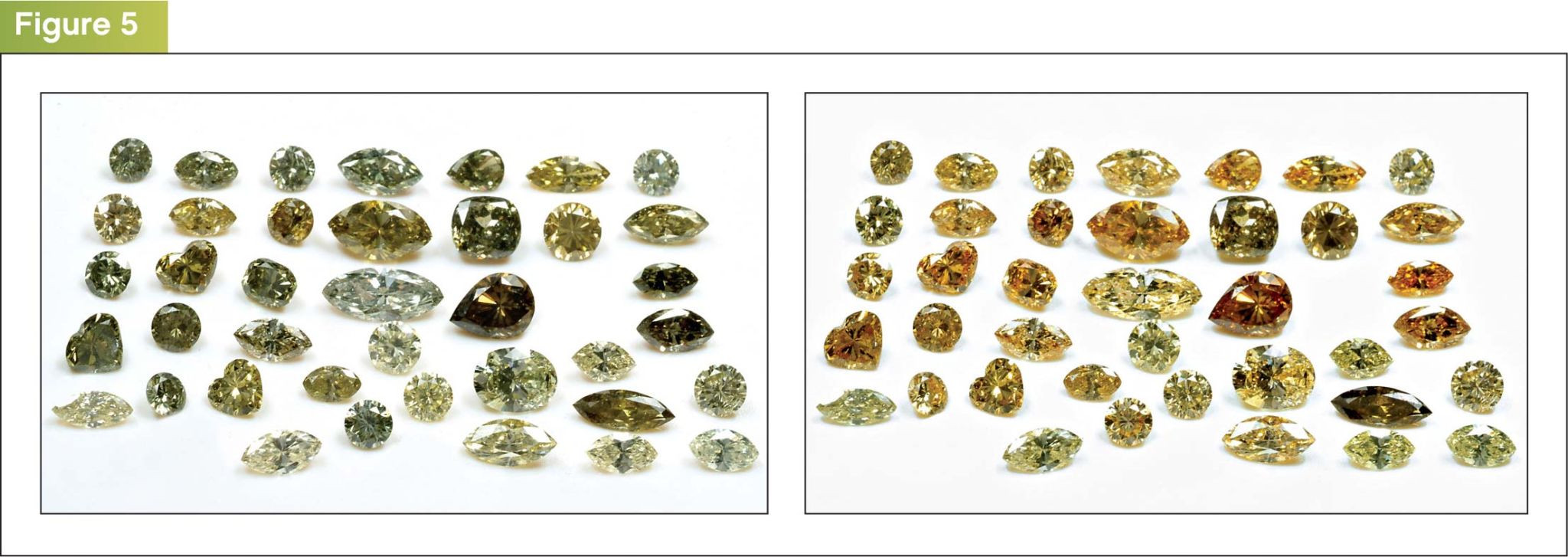

[6]Nilesh Sheth has been selling coloured and chameleon diamonds for more than 20 years in New York City and has one of the largest collections of these stones (Figure 5). “Rarity and unique colour-change characteristics combine to create a special interest in chameleon diamonds,” says Sheth, president of Nice Diamonds. “In comparing prices of similarly coloured diamonds, a chameleon typically commands a 30 to 50 per cent premium. Given greater consumer awareness, partly in response to more celebrities wearing coloured diamonds and gems, prices at auction have been favourably impacted.” Colin Ferguson of Rare Investments in Vancouver concurs, noting “more consumers are looking to own unique stones that will showcase high clarity and colour at any time of day. It’s not enough to be rare—it has to be beautiful to look at, as well.”

Coloured diamonds are becoming increasingly more popular in the Canadian market and colours other than yellow are now finding their way to jewellers and consumers. When rare size, colour, and the chameleon effect are combined, as in a 2.02-carat IF fancy greyish-greenish-yellow diamond, for example, the end result is a highly desirable and very expensive stone. Chameleon diamonds are also in demand among those who love to collect unique gem pieces, partly because they cannot be reproduced in a laboratory. Although many mainstream jewellery stores are not yet offering these coloured diamonds, they are already a special ’boutique’ commodity for consumers with a passion for the unusual and rare.

[7]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and director of CGL-GRS Swiss Canadian Gemlab Inc., in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines, and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[8].

[7]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and director of CGL-GRS Swiss Canadian Gemlab Inc., in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines, and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/OPENING-PHOTO-by-Thomas-Hainschwang-.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Figure1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Figure2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Figure3.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Figure4.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Figure5.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Brankos-photo.jpg

- info@cglworld.ca: mailto:info@cglworld.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/chameleon-diamonds-how-heat-and-darkness-bring-out-the-best-in-these-colour-changing-stones/