Choosing the right platinum alloy

by Samantha Ashenhurst | September 19, 2023 3:21 pm

By Renée Newman

[1]

[1]Have you noticed how many gold engagement rings have platinum settings (Figure 1)? This is because platinum’s high density, strength, and resistance to metal erosion makes it the most ideal metal for securing valuable gems—provided, of course, the right platinum alloy is used. The way the metal is worked during jewellery manufacturing also plays an important role in the durability of the platinum.

[2]

[2]Photo courtesy Maple Leaf Diamonds

Platinum regulations and notation

According to Canada’s Guide to the Precious Metals Marking Act and Regulations, “platinum,” “plat.,” or “platine” are quality marks provided for any article which contains at least 95 per cent platinum or, for an alloy of platinum, at least 95 per cent of platinum and iridium or ruthenium.1

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) guidelines in the United States also require an industry product be composed throughout of at least 950 parts per thousand pure platinum; however, jewellery that has less than 95 per cent but at least 85 per cent platinum also qualifies as a platinum alloy, but must indicate the parts per thousand in the platinum mark (e.g. “900Pt,” “900Plat,” “850Pt,” or “850Plat”).2 American jewellery may also be identified as platinum if it contains at least 500 parts per thousand platinum and at least 950 parts per thousand platinum group metals. The percentage of platinum and other platinum group metal(s) must be indicated in the stamp (e.g. 600Pt_350Ir).

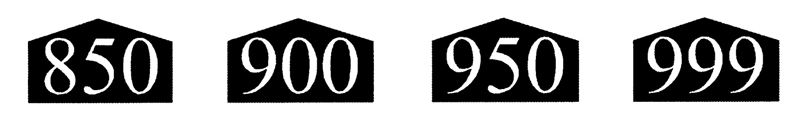

Platinum guidelines of other countries vary, but all of them allow products composed of at least 95 per cent platinum to be marked and identified as such. In the United Kingdom, a house-shaped figure surrounding the metal content is used in hallmarks to indicate a metal is platinum (Figure 2).

[3]

[3]Images courtesy Birmingham Assay Office

Platinum alloys

950PtIr

950 platinum with 50 parts per thousand of iridium (950PtIr) was once the most widely used platinum alloy. It increases the Vickers hardness of pure platinum from 56 HV to 80 HV, which is still too soft for sturdy jewellery and casting. However, 950PtIr has a high work hardenability, which can further increase platinum’s Vickers hardness up to 120 HV.

Many Edwardian and Art Deco pieces were made with 950PtIr, as the alloy’s malleability makes it ideal for the fabrication of intricate filigree and milgrain metal work (as seen in the Edwardian platinum brooch pictured in Figure 3). Given early platinum pieces were hand-worked instead of cast, their hardness was suitable for jewellery wear.

It was only in the mid-1950s that modern-day centrifugal vacuum casting was developed; however, this was not commercially implemented to a larger extend until the 1970s. According to Platinum Guild International (PGI), 950PtIr should not be used in casting because it is too soft and may likely result in bent prongs, misshapen shanks, and overall poor wear performance.

[4]

[4]Photo courtesy Heritage Auctions (HA.com)

950PtCo

950 platinum with 50 parts per thousand of cobalt (950PtCo) is a good flowing alloy recommended for casting. It has a hardness of 135 VH and can be hardened with cold hammering to 270 VH. Cobalt platinum alloys are slightly magnetic, which is regarded as undesirable for a precious metal. In fact, there have been some cases where jewellery professionals have misidentified 950PtCo as a non-precious metal because it was slightly attracted to a magnet.

900PtIr

900 platinum with 100 parts per thousand of iridium (900PtIr) is easy to cast and weld. It has a hardness of 110 HV, which is better than that of 950PtIr, but still not optimal. This alloy cannot be stamped as simply “Plat” or “Pt” because its fineness is below 95 per cent platinum. Nonetheless, 900PtIr continues to be a popular casting alloy in the United States. Kathrin Schoenke from PGI’s Platinum ABC Project says 900PtIr can be strong enough for rings if the cross sections are not too thin and if the ring gets burnished and work-hardened to at least some extent. As a drawback, however, 900PtIr it has a greyish-yellowish hue that is reflected into high-colour diamonds, which can make the stones look less valuable than they are.

950PtRu

950 platinum with 50 parts per thousand ruthenium (950PtRu) is a hard (130 HV), ductile general purpose alloy which is ideal for everyday rings. When it is cold-hammered or die-struck, its hardness increases to 210 HV. According to Schoenke, luxury companies (including Harry Winston, Tiffany & Co., Cartier, Bulgari, and so forth) use 950PtRu to ensure a metal that is “the whitest white,” which brings out the best in high-quality diamonds.

[5]

[5]Photo by Kathrin Schoenke

Dangers of choosing the wrong alloy

If an unsuitable alloy is used for jewellery, a piece’s prongs and mountings may bend and result in the loss of stones. Steve Satow, master jeweller at Generations Jewelers in Galveston, Texas, remembers having a customer show him a brand-new ring she had purchased elsewhere, which already had a loose, four-carat diamond centre stone. The customer wanted him to make the diamond secure in the die-struck, six-prong platinum head, but the prongs were so soft, Satow was able to push them to the side with his thumbnail and take the stone out right in front of her. He told the customer the only solution was to get a harder, stronger platinum head, which she did. Two years later, the diamond was still secure in the replaced setting.

The rings pictured in Figure 4 were meant as a set, but were made from two different alloys. As such, while one has stood the test of time, the other is far too weak. These are actual rings that were worn by the owner for a few months, but only one was able to withstand real-life wear.

It is especially important for eternity bands to be made with an alloy of sufficient hardness. Schoenke recommends an alloy with a minimum hardness of 130 HV, such as 950PtRu. If the wrong alloy is used, the stones could fall out when the ring is deformed, which could occur by simply grabbing a suitcase by its handle.

[6]

[6]Photo courtesy Krainz Creations

Benefits of platinum

In jewellery, platinum offers several advantages. Namely, the metal’s natural white hue enhances the lack of colour in D- to F-colour diamonds. By comparison, since white gold is created with yellow gold, the metal may be yellowish, so it is often plated with rhodium to resemble platinum. Over time, this plating can wear off, requiring the jewellery to be re-plated. The rhodium plating also complicates repair work and resizing, as this layer will burn in the heat of a soldering torch, flaking off the jewellery piece and making it impossible for the solder to flow. Meanwhile, platinum does not need to be plated.

In addition to its colouring, the metal offers several other benefits:

- Platinum does not tarnish and is not attacked by chemicals. While the same can be said about pure gold, the metals used to make gold alloys can sometimes cause it to discolour and be corroded by, for example, chlorine in swimming pools and household cleaning solutions.

- Platinum is hypoallergenic (unlike nickel white gold, which can cause a reaction in some wearers).

- Because of its higher density, platinum is stronger than white gold and retains its shape if the right alloy and manufacturing process is used. As such, it is more suitable for delicate mountings and thin prongs. Platinum prongs stay in place when formed and do not spring back like white gold prongs. Figure 5 is an example of a quahog pearl set securely in a ring using only very thin platinum prongs. According to the ring’s manufacturer, Krainz Creations, no other precious metal could secure this pearl without a post or glue.

- Platinum’s high malleability makes it a much better shock absorber than white gold, which can dampen the impact of a hard knock and potentially save a gemstone from chipping. This makes platinum ideal for the setting of coloured gemstones (Figure 6).

- Platinum pieces can come at an affordable price, while also offering the look of expensive high-end diamond jewellery. Faceted platinum beads were added to the double teardrop earrings by Platinum Born pictured in Figure 7 to make them sparkle like diamonds. The brand offers a variety of innovative platinum jewellery at price points starting at $500 retail.

- Platinum jewellery lasts longer and resists abrasion better than gold. When gold is scratched or polished, part of the metal is worn away, whereas platinum is displaced or compressed. Considering platinum does not wear thin, it is, therefore, the precious metal of choice to create heirloom pieces that can get handed down from generation to generation.

[7]

[7]Photo courtesy Fenton & Co.

Strength in design

Today, there are more platinum alloy options available than 20 years ago, and many of these are specifically engineered to fulfil certain manufacturing and lifecycle requirements. When selecting an alloy, it is important to choose one able to withstand the wear and tear a piece will be subjected to. The structural design, durability, and strength of any jewellery design is ultimately the responsibility of the creator, and only well-designed pieces with the appropriate metals will stand the test of time.

[8]

[8]Photo courtesy Platinum Born

[9]Renée Newman, GG, is a gemmologist and the author of Gold, Platinum, Palladium, Silver & Other Jewelry Metals[10] and 13 other books on jewellery and gems. She became interested in jewellery metals while overseeing jewellery quality control at the Josam Diamond Corporation in downtown Los Angeles. Her metals book is used as a textbook at the Texas Institute of Jewelry Technology. For more information about Newman and her books, visit ReneeNewman.com[11].

[9]Renée Newman, GG, is a gemmologist and the author of Gold, Platinum, Palladium, Silver & Other Jewelry Metals[10] and 13 other books on jewellery and gems. She became interested in jewellery metals while overseeing jewellery quality control at the Josam Diamond Corporation in downtown Los Angeles. Her metals book is used as a textbook at the Texas Institute of Jewelry Technology. For more information about Newman and her books, visit ReneeNewman.com[11].

References

1 To view the Guide to the Precious Metals Marking Act and Regulations, visit https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/competition-bureau-canada/en/how-we-foster-competition/education-and-outreach/publications/guide-precious-metals-marking-act-and-regulations[12]

2 See: https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/advertising-platinum-jewelry[13]

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/crop_1b-Platinum-Jewellelry.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-2.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-3.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-4.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-5.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-6.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/figure-7.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/9-Cover-photo-of-metals-book.jpg

- Gold, Platinum, Palladium, Silver & Other Jewelry Metals: https://reneenewman.com/metals.htm

- ReneeNewman.com: https://reneenewman.com/

- https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/competition-bureau-canada/en/how-we-foster-competition/education-and-outreach/publications/guide-precious-metals-marking-act-and-regulations: https://ised-isde.canada.ca/site/competition-bureau-canada/en/how-we-foster-competition/education-and-outreach/publications/guide-precious-metals-marking-act-and-regulations

- https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/advertising-platinum-jewelry: https://www.ftc.gov/business-guidance/resources/advertising-platinum-jewelry

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/choosing-platinum-alloy/