Colour blind: The challenges of grading and valuing coloured gemstones in today’s market

by charlene_voisin | February 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Mark T. Cartwright

[1]

[1]

I love coloured gemstones, and yet, I cringe each time one crosses my desk for appraisal. I suspect I’m not alone in that reaction.

The ‘advances’ in the business of altering gemstones are moving far more rapidly than our ability to detect and/or understand them. By the time knowledge of any specific treatment is widespread, there is often an ‘improved’ version of that technique or something totally different in the market. And that’s just half the battle. Putting a value on something the markets are ignoring or haven’t had time to react to becomes nearly as problematic as detecting the alteration itself.

[2]

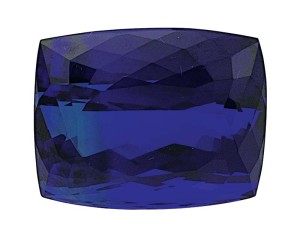

[2]The concept of market value is predicated on a series of conditions; among them is that buyer and seller are equally well-informed or well-advised. In today’s coloured gemstone market, that’s often not the case. For a fairly recent example of how the disparity in knowledge can impact value we need look no farther than the beryllium diffusion treatment of sapphires.

When beryllium treatment was initially utilized, and before it had been discovered or disclosed, extraordinary quantities of corundum began appearing in the market in a dazzling array of colours, including hues that had previously been extremely rare such as Padparadsha, vivid pinks, and oranges. The gemstone markets eagerly absorbed the stones at then-current prices; the sellers at the source, however, knew something about the product the buyers didn’t.

Even as suspicions arose, many buyers were perhaps too willing to believe the lies they were being told and prices for the stones remained fairly firm. However, once it became known the colours were artificially induced and the starting materials were actually low-value stones, prices plummeted dramatically. Appraisers and consumers were caught in the middle of a fiasco, as the market destabilized and stones that had been selling for $400 per carat were priced at $30 per carat within the month. As soon as most of us learned to look for and recognize the signs of beryllium diffusion, the ‘burners’ in Thailand were discovering new ways to conceal those indicators from all but the most sophisticated laboratories. At present, the small-laboratory gemmologist will find many of the beryllium-diffused stones impossible to detect.

Playing along?

[3]

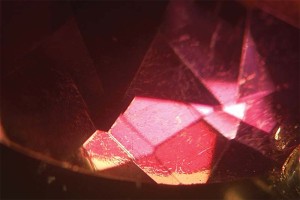

[3]Each time I examine a client’s coloured gemstone, I try not to imagine what tomorrow’s ‘beryllium diffusion’ disaster might be. I have little doubt that such a disaster will happen—the gemstone treaters are far too inclined to play hide and seek with the truth, and our industry is far too willing to let them. One example of our willingness is the issue of flux-filling rubies. It’s well understood the only reason rubies are packed in borax when heat-treated is because it causes the ‘healing’ of fractures and/or the filling of those fractures with borax glass. Yet, as an industry, we’ve decided to believe the story we’ve been told that such infilling is “just an unavoidable byproduct” of the heating process. How convenient that by playing along with the charade we reap the benefit of a steady supply of fairly inexpensive rubies, while being able to tell most of the truth to consumers.

In my appraisal document, I have a fairly typical boilerplate disclosure that reads something like, “It was assumed that all coloured gemstones were altered in some way to improve their appearance. Such alteration is commonly accepted practice in the gemstone industry when properly disclosed and not intended to deceive. Prevailing prices in the markets are based on this assumption of treatment”¦”

[4]

[4]I know that statement is a partial truth intended to soften the reality of what’s going on in the gemstone industry. Every treatment is intended to deceive; there’s no other reason to alter a gemstone’s appearance. Some alterations are simply more ‘acceptable’ than others, and there seems to be no logic in deciding which those are. For instance, the use of beryllium diffusion in the heat treatment of corundum is somehow a bad thing, but the same process using oxygen in place of beryllium is okay and doesn’t require explicit disclosure. Similarly, filling an emerald’s fractures with a blend of natural and synthetic oils or resins is okay, but the use of synthetic epoxy resin alone is only okay if the hardener isn’t added?!

So many things could have been done to so many different gemstones that simply detecting them could take hours, assuming we have the equipment and the ability to do so. Once detected, we can only imagine our client’s reaction if we told them their ruby had started out as a semi-translucent, heavily fractured purple pebble until it had been heated to its melting point for 20 to 30 days in a soup of chemicals that radically altered its colour, clarity, and composition. No wonder so many jewellers gloss over the disclosure of extreme gemstone alteration with the euphemism ‘enhancement,’ while appraisers resort to short, generic statements.

What’s out there?

[5]

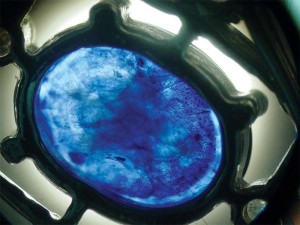

[5]Leaving aside the huge can of worms that is the current reality of alterations to members of the corundum family, what else should we be looking for and how should we be looking? The infusion at fairly low temperatures of high-refractive index glass seems to have become nearly ubiquitous. There are reported examples of glass infilling of tourmaline, opal, beryl, topaz, spinel, tanzanite, and many other stones. Along with trapped gas bubbles, the ‘flash effect’ seems to be a common feature of that type of treatment, and we should be looking for those indicators in every gemstone we examine. Coatings—primarily applied to the pavilion or girdle—appear to be almost as widespread as glass infilling. Tanzanite seems to be one of the most commonly encountered coated stones, but as gemmologists/appraisers we should be alert to the possibility that any stone may have been coated. Since most coatings are superficial, fragile, and thin, they are very prone to scratches and wear along exposed edges. Careful microscopic examination using a white diffuser plate helps detect surface treatments applied to transparent gems. Although often mentioned as a viable alternative, tissue paper or any other type of paper produces a mottled background that makes it significantly less effective than a diffuser plate made of glass or Mylar. ‘B’ jade is a different story, but the ultraviolet fluorescence of the polymer used as a filler can make its detection less difficult. You will need all the ‘weapons’ in your arsenal: immersion, polarized lighting, reflected light, UV microscopy, shadowing, and, of course, extreme magnification.

So far, I’ve only mentioned gemstone treatments and merely a few of the ones that are possible. Time and space limitations, as well as my inability to speak rationally on the subject, preclude me from delving into the morass of synthetic gemstones. Suffice to say that even in my fairly isolated part of the world, I’ve seen several examples of synthetic stones that were intentionally altered and then treated in an effort to disguise their laboratory origins. Most of the stones I’ve examined were corundum, however, one was an emerald. I no longer assume a stone is natural simply because it has undergone significant treatment.

[6]

[6]In the rapidly changing world of gemstone treatments, it is probably safe to believe that even markets are making assumptions about the products being bought and sold. As we research values within the various markets, one of the concerns we should have is of how well-informed buyers and sellers might be. As an example, it’s highly probable an individual selling a piece of jewellery on eBay has no idea what may or may not have been done to the gemstones. The same assumption could probably be made of most levels of trade within the used (i.e. secondary) retail market. Even in the primary retail markets, compliance with disclosure requirements seems to be somewhat inconsistent; does that indicate some retailers don’t know which treatments have been done to which gemstones in their showcases, or simply that they’d rather not say?

As appraisers, our primary concern is whether inconsistency has an impact on value. Are stores that fully disclose their rubies have been subjected to high heat with flux healing/filling forced to sell them for less than their competitors who simply acknowledge (only if asked) that “most gems are enhanced”? If the answer is yes, does that indicate it is the fact of treatment or the level of disclosure influencing the ruby’s value? If it is the latter, are we justified in assuming such stones have a lower value in most levels of trade? The answers to questions like these are difficult to know, but they can help shape how one approaches the valuation of coloured gemstones within their local markets.

Does that come in a size 9?

Consumers rely on our skills as gemmologists to protect them from the unscrupulous and misinformed. We’re quickly finding ourselves in a world requiring skills and technology that we may not possess. Should we simply throw up our hands and go get a job selling shoes? Maybe eventually, but in the meantime, we need to be honest with ourselves, our clients, and users of our reports. Everyone deserves to clearly understand what assumptions were made, how they may impact the value if proven wrong, and why we were forced to make those assumptions. I mentioned earlier the concept of market value presumed equally well-informed buyers and sellers. We need to recognize the foundation of an accurate appraisal is a well-informed appraiser. It’s not simply about knowing what we’re looking at—that’s just the first step.

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ammolite-pendant.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/90ct-tanzanite.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/diffusion-filter-in-action.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/scratched-pavilion-coating.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fake-rubellite-ring.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/fake-rubellite-coating.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Mark-Cartwright.jpg

- gemlab@cox-internet.com: mailto:gemlab@cox-internet.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/colour-blind-the-challenges-of-grading-and-valuing-coloured-gemstones-in-todays-market/