A simple twist on a classic design

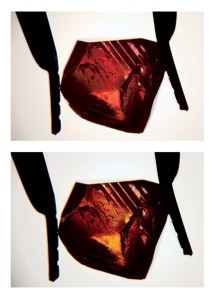

When I created my polarislides, I purchased the highest-quality polarizing film I could find and some two-part plastic frames. I then added a thin sheet of white Mylar to one side of the frame that would become the ‘polarizer’ plate. Mylar acts as a translucent diffuser. When the slide is placed on the microscope’s light well with the Mylar closest to the light source, it creates an evenly distributed light field for the polarizer, making the entire width of the slide more functional. If placed on the light well with the Mylar closest to the microscope lens, it acts as an excellent white diffuser. Regardless of how or where you acquire your set of polarizing filters, I highly recommend finding a way to modify one of the pair the way I did. Okay, we now know how, but why would we want such a tool sitting on our desk?

Let’s first consider the set of filters when used together. Obviously, the one with the Mylar rests on the microscope stage. If necessary, I use a couple of small dots of StickyTac or another putty-like temporary adhesive to affix the filter in place so I can tip the microscope for more comfortable viewing. Normally I adjust the analyzer plate to the ‘crossed’ position before beginning the examination. Since I don’t usually plan to linger (time is money, after all!), I simply raise the microscope head, and while holding the analyzer in one hand, I move the stone under it with either the other hand or stone holder. Keep in mind we’re dealing with stones mounted in jewellery, so it’s important to be able to easily and rapidly manipulate the piece to peer through the tiny ‘windows’ the setting gives us.

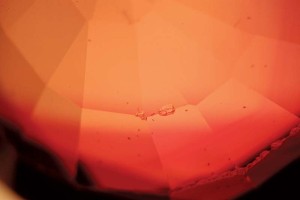

Of course, using your microscope’s zoom feature can make those tiny windows appear much larger. With crossed polars, we can find growth features, such as the chevrons in hydrothermal synthetics, twinning planes, Brazil-law twinning, and the optic axis. We can also discern whether an inclusion is a crystal or a void, fillers within fractures, and many other potentially diagnostic internal features that are invisible in ordinary light. As one rotates the stone under the crossed polarizers, any pleochroism may become apparent as well. Locating and recognizing the various forms of anomalous double refraction (ADR) in diamonds is an important test to master utilizing crossed polarizers with microscopy. While the ADR test won’t positively identify every synthetic diamond, it can help us determine which stones should be subjected to advanced testing. Sometimes I use polarizers to differentiate between reflective graining and feathers in a diamond.

No matter what tests we’re performing, I believe knowing what a stone isn’t can be as useful as knowing what it is; adding the capability of polarization to your microscope can be a powerful tool for making separations quickly and easily.