Crossed polarizers: The value of simple instruments

by charlene_voisin | August 1, 2014 9:00 am

By Mark T. Cartwright

[1]

[1]

In a previous issue of Jewellery Business, I introduced readers to a few of my favourite tools and briefly described some of their uses. Perhaps it’s a good time to provide a bit more detail and delve into specific techniques and how the information they provide can help us do our jobs more efficiently.

Several years ago, I had the idea of creating various small ‘pocket’ instruments for gemmologists and gemstone enthusiasts. While that enterprise didn’t quite change the world or my bank account, it did allow me the opportunity to think about how to maximize the utility of small gemmological tools. It also left me with a variety of fun gadgets to play with; after all, who among us doesn’t enjoy that? The one I use most often is a slightly modified set of polarizing plates that I dubbed ‘polarislides.’

Dust off your polariscope

[2]

[2]As gemmology students, we were all exposed to the polariscope, and many of us still own one. We might even use it every once in a while, although I’ll confess it’s been well over a month since my last encounter with a standalone polariscope. On the other hand, I use my modified polarizers on a daily basis. The difference is I can also use my polarislides in conjunction with my microscope and the modifications allow me to use them for a variety of tests.

Classically, a polariscope is used to determine whether a stone is singly refractive (i.e. isotropic), doubly refractive (i.e. anisotropic), or an aggregate. It is also used to locate the optic axis. With the addition of a conoscope, wave retardation plate, and/or a quartz wedge, one may also determine a stone’s optic character, optic sign, and in the case of quartz, identify the ‘handedness.’ All this can be very useful information when identifying a loose gemstone; every gemmologist should know how to perform and interpret the tests. One of the ‘problems’ we as jewellery appraisers encounter when trying to make use of a polariscope is that we’re usually dealing with mounted gemstones and often with relatively small ones. The limited viewing area we’re typically afforded can make it difficult or impossible to correctly interpret the stone’s reaction to crossed polarizers. The solution is magnification.

Polarizing microscopes are specialized instruments most commonly found in a mineralogist’s laboratory; however, adapting a standard gemmological microscope to perform similarly isn’t difficult or expensive. Some people use polarizing filters designed for photography, others purchase polarizing film online or from other sources to create their own. If you choose to purchase photographic polarizers, be sure to use the linear variety, rather than circular polarizing filters. Circular polarizers are most commonly used for digital cameras and aren’t really suitable for our purposes.

A simple twist on a classic design

[3]

[3]When I created my polarislides, I purchased the highest-quality polarizing film I could find and some two-part plastic frames. I then added a thin sheet of white Mylar to one side of the frame that would become the ‘polarizer’ plate. Mylar acts as a translucent diffuser. When the slide is placed on the microscope’s light well with the Mylar closest to the light source, it creates an evenly distributed light field for the polarizer, making the entire width of the slide more functional. If placed on the light well with the Mylar closest to the microscope lens, it acts as an excellent white diffuser. Regardless of how or where you acquire your set of polarizing filters, I highly recommend finding a way to modify one of the pair the way I did. Okay, we now know how, but why would we want such a tool sitting on our desk?

Let’s first consider the set of filters when used together. Obviously, the one with the Mylar rests on the microscope stage. If necessary, I use a couple of small dots of StickyTac or another putty-like temporary adhesive to affix the filter in place so I can tip the microscope for more comfortable viewing. Normally I adjust the analyzer plate to the ‘crossed’ position before beginning the examination. Since I don’t usually plan to linger (time is money, after all!), I simply raise the microscope head, and while holding the analyzer in one hand, I move the stone under it with either the other hand or stone holder. Keep in mind we’re dealing with stones mounted in jewellery, so it’s important to be able to easily and rapidly manipulate the piece to peer through the tiny ‘windows’ the setting gives us.

[4]

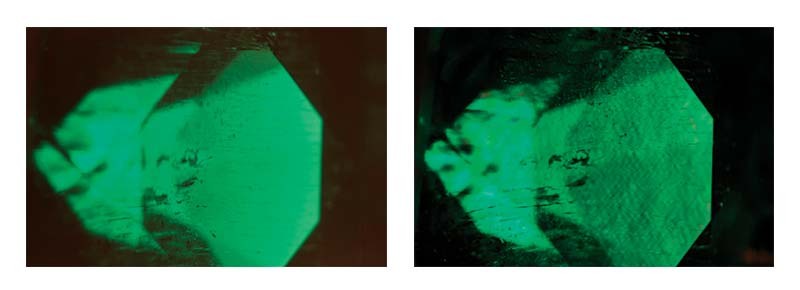

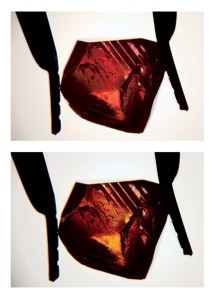

[4]Of course, using your microscope’s zoom feature can make those tiny windows appear much larger. With crossed polars, we can find growth features, such as the chevrons in hydrothermal synthetics, twinning planes, Brazil-law twinning, and the optic axis. We can also discern whether an inclusion is a crystal or a void, fillers within fractures, and many other potentially diagnostic internal features that are invisible in ordinary light. As one rotates the stone under the crossed polarizers, any pleochroism may become apparent as well. Locating and recognizing the various forms of anomalous double refraction (ADR) in diamonds is an important test to master utilizing crossed polarizers with microscopy. While the ADR test won’t positively identify every synthetic diamond, it can help us determine which stones should be subjected to advanced testing. Sometimes I use polarizers to differentiate between reflective graining and feathers in a diamond.

No matter what tests we’re performing, I believe knowing what a stone isn’t can be as useful as knowing what it is; adding the capability of polarization to your microscope can be a powerful tool for making separations quickly and easily.

One can work as well

[5]

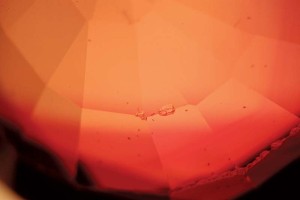

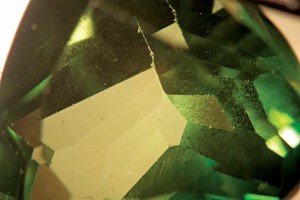

[5]As much as I enjoy polarizing microscopy, I probably use just the single polarizing plate with Mylar (the polarizer) far more often. With the Mylar down, I can use it as a dichroscope by simply rotating the stone (or jewellery) in multiple directions. Using the microscope’s zoom, one can even use this technique for melee gemstones, as long as the polarized light can pass through the stone. If it can’t, switch to the analyzer plate, and while illuminating the melee with fibre optic or a penlight, rotate the stones below the filter or the filter itself if that’s more convenient. As I mentioned previously, flipping the polarizer so the Mylar is on top creates a superb translucent white filter. This position allows me to easily detect colour zoning and is a great background for viewing inclusions. With stones held at oblique angles, the white background provides a good reflective surface for detecting coatings and surface features on gemstones and diamonds. If it’s advantageous, the filter can be positioned above or to one side of the stone to provide the surface reflection needed to detect some surface anomalies.

Polarized light can also be useful in spectroscopy and, of course, with a refractometer. For use with a spectroscope, positioning the polarizer plate with Mylar toward the light source can be very useful for examination of anisotropic gemstones, since the individual rays can be studied separately by rotating the slide. When used with a spectroscope simply as a light diffuser, it can enhance one’s ability to see the absorption spectrum of some gemstones. Rotating an analyzer in the viewing path of a refractometer is a commonly known technique for determining a gemstone’s birefringence.

The fun never stops (unless you let it)

I hope this discussion inspires you to acquire a set of polarizing filters for your microscope and if you’re adventurous, modify one of them with white Mylar. We all look for ways to make our jobs easier and faster; I’ve found this simple gemmological instrument, when properly utilized, can do just that. My hope is readers of this magazine will never stop learning and seeking new ways to solve problems; the savings in time and energy can pay significant dividends and also be a great way to add even more fun to the best job in the jewellery industry.

[6]Mark T. Cartwright is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist appraiser (American Society of Appraisers), independent certified gemmologist appraiser (American Gem Society), and GIA graduate gemmologist, who has provided gemmological and jewellery appraisal services since 1983. He can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[7].

[6]Mark T. Cartwright is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist appraiser (American Society of Appraisers), independent certified gemmologist appraiser (American Gem Society), and GIA graduate gemmologist, who has provided gemmological and jewellery appraisal services since 1983. He can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[7].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/hydrothermal-growth-crossed-polars.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Emerald-liquid-inclusions.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/polarizer-as-dichroscop.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/diffusion-treated-sapphire-white-diffuser.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/simulated-tsavorite-vapor-coating-w-white-diffuser.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Mark-Cartwright.jpg

- gemlab@cox-internet.com: mailto:gemlab@cox-internet.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/crossed-polarizers-the-value-of-simple-instruments/