Cut & polished: When it comes to gemstones, sometimes less is more

by charlene_voisin | June 1, 2012 9:00 am

By Diana Jarrett

Gemstone and diamond cutters understand the subtle and not-so-subtle impact of expert cutting and polishing on a stone’s appearance and value. Educating the public on the difference in price for this precision work? Well, that’s another story.

Show and tell

With the right slice, expert cutters can transform an insipid pebble into a coveted treasure. Yet, surprisingly, retailers don’t always understand how to express to clients the vagaries of gemstone cut-to-value. Knowing what impacts value in gemstone cuts can help arm retailers to point out these differences, and is a great tool for reinforcing the value of their jewellery with clientele. This teaching opportunity might just convert a customer from being a mere consumer to a collector, making the retailer infinitely more valuable to their client.

Before another cut is made on an already finished stone, cutters assess what recutting will produce for them. If the stone belongs to a customer, they must reconcile his or her expectations with what is possible.

Seeing is believing, says jewellery designer Melissa Spivak of Toronto’s Samuel Kleinberg.

“When we educate our clients on cut, we explain that a poorly cut diamond will leak light out at the bottom or the sides, resulting in a dull, flat-looking stone without a lot of brilliance,” she explains. “We show an excellent cut stone and a poorly cut stone side by side so customers see the difference. Once the client has a better understanding of cut, they appreciate the value.” Even good stones can be nudged to perform better via excellent cutting. “I really believe the true beauty of a diamond is unleashed when it’s cut to an excellent grading,” she says.

Intended consequences

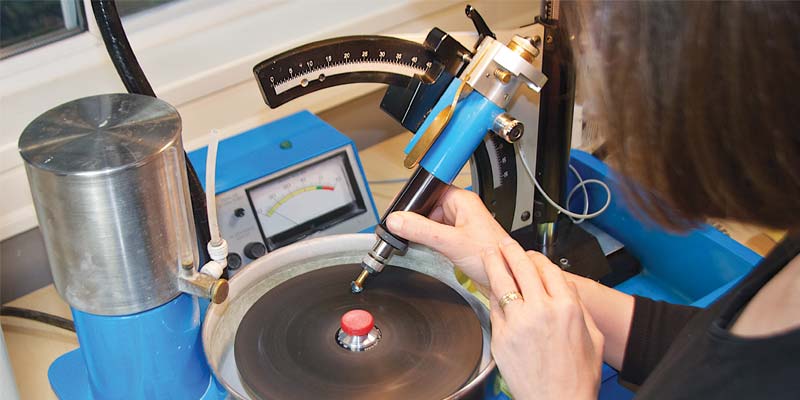

Vancouver-based veteran gem cutter Lisa Elser has decades of experience and Swiss training to support her expertise in assessing cut-to-value with gemstones. Not only is a well-cut gem more appealing, but it has a direct impact on salability. “I often buy poorly cut gems and recut them,” she says.

Tanzania’s ban on exporting its namesake rough means nearly all Elser’s tanzanite goods are cut there. Once home, she recuts the stones herself. Elser recalls a specific acquisition. “I lost about a carat in weight, but the recut gem is far nicer and sold quickly,” she says.

“I also find that for some stones like spinel and sapphire in particular, it can be easier to find poorly cut gems for recutting, than quality rough material.”

Gem cutter John Dyer of John Dyer & Co., in Minnesota buys rough from all over the world. While a fine gemstone cut to exquisite proportions reflects value in its price, he often finds well-cut stones are not that much pricier than their poorly fashioned counterparts when the cost of recutting them is factored in. Prices paid for poorly cut gems often fluctuate, he reports. “This varies a lot due to labour cost though, so the cheaper the gem material, the more of a price difference the cut will make.”

Well-cut gems are far more brilliant, Dyer adds. Poor cutting that results in windowing effectively eradicates brilliance in that portion of the gem. “Even to an untrained eye, a well-cut gem is just brighter.”In addition, setting a well-cut stone is more easily accomplished. “There are no knife-edge girdles, crooked pavilions, or girdles that wander up and down,” he explains.

Pricier coloured stones like sapphire, ruby, or emerald are always cut to maximize weight retention, since larger carat sizes in these gemstones are rarer and earn the highest prices. But weight retention should never be done at the expense of beauty. Often, a critical slice can up the clarity grade of a stone, as well as increase its brilliance and symmetry.

Vancouver-based cutter Anthony Lloyd-Rees of The Gem Doctor recalls an opal purchased by a customer for a few hundred dollars while visiting Australia. After returning to Canada, she decided to have it set it in a better-quality ring. When he examined the stone, Lloyd-Rees realized she had purchased a Lightning Ridge rub, which is an opal rough with a small area polished away to peek inside for a look at the actual stone. Recutting the stone was definitely to the client’s advantage. “She ended up with a brilliant opal worth many several thousand dollars, although quite a bit smaller than her original stone.” Revelations of misidentification are apparently one of the perks of getting a recut, Lloyd-Rees notes. A supposedly white sapphire stone brought to him for recutting turned out be a much more valuable scheelite.

Recutting in Canada is relatively expensive and generally reserved for higher-ticket items like sapphires, explains Alex Barcados, owner of C.D. Barcados in Toronto. There is also less risk involved in recutting an expensive stone over working with the rough. Â

“An existing gemstone will already be heated, and the inclusions and colour zoning clearly visible,” he says. “This allows an experienced cutter to evaluate the gemstones to select ones to recut that will undergo the best improvements.”

I’ll take the leftovers, please

Most consumers have little understanding of the recutting and polishing process. When it comes to diamonds especially, clients shiver at the idea of placing their stone on the polishing wheel, even to enhance its value, raise its clarity, and render it more valuable. Since pricey gems and diamonds are valued in part by their carat weight, few jewellery collectors embrace a recut. It’s not uncommon for consumers to request the ‘leftover pieces’ from a recut.

“Most owners balk at having their already finished diamonds cut,” says diamond cutter Maarten de Witte, executive director (USA) of Embee Diamond Technologies in Saskatchewan. “To remove weight is to remove value. Or, so they think. Actually, all diamonds are valued by what they would be worth if they were cut to state-of-the-art standards as modern round brilliants, which today means ideal performance.” Simply put, better performance improves value.

De Witte recalls a diamond so poorly cut, it languished in inventory for years. Its only function was as a comparison for clinching other diamond sales. In de Witte’s hand, the terribly cut stone found new life and a quick sale at full price. “The girdle was running about 20 degrees out of parallel with the tiny table,” he says. “So you can imagine the crown and pavilion facet angles were all over the map. To top it off, the diamond was noticeably off-colour and I/2 in clarity. Against the advice of all other cutters, I re-worked it to have ideal light performance and was even lucky enough to get excellent polish. It started off a 1.78-carat and came out a 1.33-carat, I colour, I/1 clarity.”

Sam Poddar, president and chief executive officer (CEO) of Byrex Gems in Toronto, recounts his own recut story. “We bought a large yellow diamond with VVS clarity. The colour was fancy intense, but more on the lower side of the colour spectrum. We approached an expert diamond cutter in New York to evaluate the possibility of improving its colour and clarity. With slight modification in the cutting, the colour of the stone improved and the clarity went up from VVS to flawless. This enhanced both its salability and value.”

Valuable coloured stones undergo the same scrutiny at Byrex. “Similarly, we had some poorly cut old stock of fine sapphires. Once we recut them, the salability and the value went up drastically,” Poddar adds. “In general, we always look for these kinds of stones where we can use our cutting resources to enhance the value.”

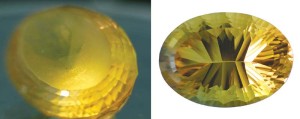

Maximizing beauty should always trump weight, says Dyer. A recut on a 142.59-carat lime citrine resulted in more than a 50 per cent weight reduction, bringing the stone to 69.69 carats. Losing so much of the stone was worth it, he notes. “Now the gem is symmetrical and far brighter, with a better polish and no window. It’s also easier to set.”

Elser finds that while most jewellers recognize well-cut stones, they may not seek them out or be willing to pay a premium. “My client base is smaller, but they love well-cut gems and unique designs,” she says. And their enthusiasm spreads to consumers.

“I’ve seen their businesses grow year after year, even through the down times” says Elser, adding collectors feed off retailers’ excitement and willingness to promote well-cut gems.

How the dealers deal

Gem cutter Rogerio Graca, owner of Pristine Gemstones in Victoria, supplies cut gemstones to jewellers throughout Canada. He notes the use of traditional machines in cutting centres in the third world offers a partial explanation for poorly cut stones.

“If consumers were better informed, the demand for finer cut gemstones would speed up the transition to precision-cut machines in the major cutting centres,” Graca says, noting the economic and cultural barriers many countries face. “Ultimately, it is up to those of us in this industry to continue educating the general public about gemstones.”

The preference to buy poorly cut diamonds and gemstones and recut them to enhance their quality and appearance is one way to add margin to the bottom line, as well as speed up the sale of goods.

Dino Giannetti, co-owner of Toronto’s 18Karat, says grasping the impact of cut-to-value is one facet of the business retailers should consider embracing. “While we live in our own little world, we need the right people behind us like expert cutters and appraisers to lend trustworthy advice, so we can make informed decisions when a recut is being considered,” he says. For instance, with an antique stone, one must consider the slight chance it could fracture from internal stresses unique to a well-worn stone that would be not be present in one newly cut.

Giannetti says he sees a lot of high-end family heirlooms come through his doors. Often, customers are reluctant to recut a poorly cut gemstone, even when the result can up the value and brilliance. “While one can make a case for recutting to release the stone’s potential, often sentiment trumps common sense,” he finds. “What we are dealing with is emotions, after all.”

Charles Carmona, author of The Complete Handbook for Gemstone Weight Estimation, underscores the challenges facing cutters when considering a recut. “Each gem species presents unique attributes and challenges to cut properly, taking into account the shape of the rough, the orientation of the optic axes, and clarity considerations,” he says. “It’s a pleasure to discover a well-cut stone and to appreciate the cutter’s knowledge and skill that went into making it so. We’re reminded of it every time we see a native cut stone coming out of an old mounting. It’s often an agonizing decision whether to ‘just fix it’ or to go further and make it beautiful, but smaller.”

Diana Jarrett is an award-winning trade journalist and graduate gemologist (GG). In addition to being a member of the National Association of Jewelry Appraisers (NAJA) and a registered master valuer, Jarrett is a popular conference and trade show lecturer. She writes a syndicated column called “The Story Behind the Stone” for the Southern Jewellery News and Mid-American Jewellery News and is also a writer for magazines such as Texas Jewelers, New York Mineralogical Club Bulletin, and the gem trade blog, Color-n-Ice.

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/cut-polished-when-it-comes-to-gemstones-sometimes-less-is-more/