Are your designs a little sketchy?

by carly_midgley | December 6, 2017 10:46 am

By Kate Hubley

[1]

[1]Inspired by everything around us, most jewellery designers keep a sketchbook on hand at all times. Ideas keep popping into our imaginations. Some are fleeting, while others stay with us and even inhabit our dreams. How many of us wake up in the wee hours and reach for a pencil and paper just so we don’t forget that flash of inspiration?

An idea is one thing. However, bringing it to life through disciplined design is when the real creative process begins.

My wax is waning

I really dove into jewellery design with wax carving. I would have an idea in my mind’s eye and start carving organically, changing details as I went along. I could do that because I could feel my way around wax with that mind-hand connection. Plus, wax is quite forgiving—you can always go back with a warm tip and fill in anything that didn’t quite work. However, not every project was a success story, and many would end up shoved to the back of a drawer in my studio.

I could also just start over a few times until I got it right. As a matter of fact, I have even heard some very established bench jewellers say they include failure in their work plan in the event they have to start over—sometimes more than once.

In the past, I was fine with my namby-pamby mindset because jewellery design and fabrication was my “expensive hobby,” not my career. Today, as I rifle through my drawer of a decade’s worth of half-finished ideas, I realize I often skipped a crucial step: drawing and draughting. I call it the “thinking phase,” for design is not simply a creative idea—it is also architecture, engineering, problem-solving, and innovation.

As the world-renowned, award-winning Canadian designer Reena Ahluwalia puts it: “Alongside creativity, originality, and skills, I believe a successful designer is a mix between an artist, thinker, inventor, engineer, visionary, and strategist.”

Blurred lines

In a time-is-money world, no one can really afford to squander hours—and that includes me. I have also come to accept although I am pretty good at wax carving, my concepts are more sophisticated than my hand.

Therefore, like many of us, I turn to my CAD designer to help bring my concept to life. It is often faster, the work more precise, and the outcome more predictable. (I still wax carve quite a bit by hand, but it’s more for exploration and mediation than production.)

[2]

[2]Photo courtesy Kate Hubley

I have a very good working relationship with my favourite CAD designer. He understands my esthetic and often suggests details that improve the mechanics of the design. That said, I have come to rely on him to do some of my thinking for me.

Recently, I handed him a rudimentary sketch of a new design. I thought he was able to read my thoughts and interpret my grandiose arm gestures as I mimed the finer details of my concept to him.

When he showed me the 3D model of my design, I woefully admit I uttered the words: “That is not what I had in mind.”

To that, he replied: “Well, your design is not logical.”

That, according to Joseph Yabriydi of Montréal-based CAD design company Empire de Bijoux, is all too common.

Back to the drawing board

[3]

[3]Image courtesy Shelly Purdy

After my CAD designer clearly drew his red line,

I went back to my draughting table and reworked my plans, calculating and measuring to scale in order to get back into his good graces—and develop a more outstanding design.

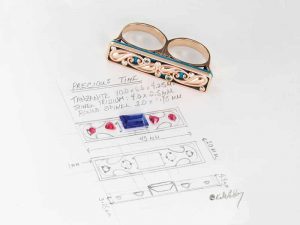

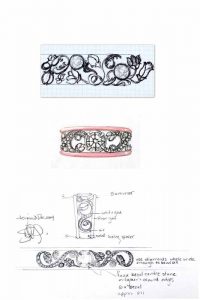

What I had given my CAD designer was what world-class Canadian designer and goldsmith Shelly Purdy calls an inspirational drawing,” also known as a counter sketch. This is a crucial part of design, and one that comes naturally to jewellery designers. Purdy describes the process as thinking with her pencil, as her sketches flow automatically from her head to her hand.

Rémy Rotenier, a celebrated French jewellery designer now residing in New Mexico, is internationally acclaimed for his stunning lifelike illustrations and gouache renderings. He describes the drawing process as a personal organic relationship with design, where nothing separates you from your pencil and where the designs want to come to life because they want to exist.

As Rotenier describes it, “Like a little voice in the dark, they call out: ‘draw me.’”

Technically, you need a blueprint

The free-flowing exploratory drawings Purdy discusses are very helpful to your CAD designer, but they are not enough. They are probably not enough for you either if you are doing your own fabrication. You need to develop a technical drawing—a blueprint, as it were.

“The inspirational sketch needs defining,” explains Purdy. “That is when I tap into my architectural-draughting background to create my working drawings with technical details. Yes, it takes time, but also saves time in the end.”

Being a goldsmith, Purdy also leverages her extensive knowledge of jewellery fabrication at the technical drawing stage to make key decisions based on tolerances such as wall thicknesses, prong height, and so on.

[4]

[4]Image courtesy Rémy Rotenier

Ahluwalia, who is also a professor teaching in universities and design schools around the globe, underscores the need for detailed drawings.

She says, “After concept exploration, technical drawing is a great way to precisely detail out your design from all angles. To my jewellery students, I always say that each millimetre should be well considered. After all, you are dealing with diamonds, gemstones, and precious metals.”

Robert Ackermann, a California-based, award-winning Swiss goldsmith, lecturer, and founder of Les Ateliers online jewellery design learning centre, also emphasizes the importance of understanding mechanical tolerances, using pavé as an example.

“You can’t just draw tiny circles and say, ‘There, that’s pavé.’ You have to understand how the hard stones and malleable metal work together,” he says. “You have to lay out your work proportionately so you know if it can, indeed, be fabricated as you envision.”

Looks good on paper…

[5]

[5]Images courtesy Claudio Pino

What about wearability? Elizabeth Brehmer, director of jewellery manufacturing arts (JMA) operations at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), points out the institute’s on-campus jewellery design curriculum includes a focus on mechanics and functionality.

“Students do not merely sketch out the elements of jewellery. They gain a clear understanding of how they work together and how a design will fit, feel, and lay on the human body,” she says.

How comfortable is that ring? How will those earrings fall? How will that stone look from different angles? These are also vital considerations at the pre-CAD and pre-fabrication stages.

Owning your designs

After I sat down and spent the time needed to do my due diligence and produce more technical drawings, I also felt a greater sense of ownership over my designs. Ahluwalia eloquently affirms this sentiment of discipline and concept ownership.

“Each design I have ever created is a Reena Ahluwalia original and the design concepts are entirely developed by me. I personally create my blueprints (i.e. technical drawings) by hand,” she explains. “By nature, I am super precise and pay high attention to details. I find this connection while creating intimate—each line letting me decide, fine-tune, and think deeply of the minute details and functionality of each piece. Of course, after my technical drawing and illustrations are done, it can go to the CAD stage, but not to start off with.”

[6]

[6]She also says, “Being a professor of technical drawing, this is an area that is very close to my heart. The field of jewellery is technical, so I feel that is a must-have skill for goldsmiths, designers, and jewellery artists.”

Down to a fine art

The third form of design drawing is freehand illustrations in perspective and to scale. This is the art form that has earned Rotenier such widespread notoriety and love in the jewellery industry—and with his private clients.

Above and beyond the sheer beauty of freehand rendering, Rotenier says it gives you a better estimation of the materials needed to create the piece. It also lets you plan your work without all the surprises you may otherwise encounter, because—for all intents and purposes—the piece already exists.

Freehand rendering: Your lines of communication

[7]

[7]Photo courtesy Reena Ahluwalia

When you can pick up a piece of paper and pencil and sketch freehand in perspective, you instill trust, especially with a private client.

Rotenier explains, “They are vulnerable. They open up to you. You listen and bring their emotion to life before their very eyes.”

In this case, you are more likely to close the deal. Ackermann adds you also have an easier dialogue with your CAD designer or any other outside resource you turn to, because you have been able to work out any design issues beforehand.

Not all designers outsource—or even use CAD at all

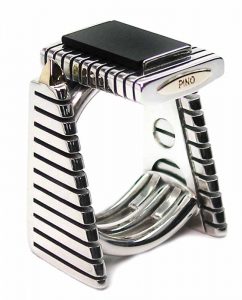

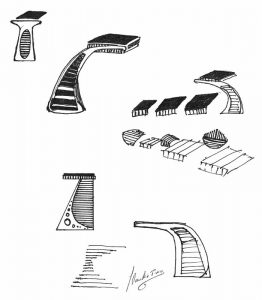

Claudio Pino is a Montréal-based fine art jewellery designer and goldsmith whose unique creations have starred in The Hunger Games and Stephen King’s The Dark Tower. He creates one-of-a-kind sculptural rings, completing each step of the design, sketching, piece-by-piece hand construction, stone cutting, faceting, and setting processes in his studio. Upon seeing his crisp sketches and clean renderings, I asked him about the role of sketching in his work.

“Sketching is a very important step in my creative process. It is in fact essential! It is a way for me to explore different possibilities and ideas and do some research,” he answered. “From concept to completion, each ring evokes new challenges while combining my desire for innovation and elegance. However, I don’t need high-precision technical drawings, as I create only one-of-a-kind pieces, with hand fabrication techniques (no casting) and without subcontracting.”

The learning curve

“You need to learn about curves, beauty lines, proportions, and colours,” says Rémy Rotenier. “Otherwise, you’ll get stuck in a cookie-cutter world.”

I know the more disciplined time I dedicate to the sketching and technical draughting stage, the more elevated my designs will be. Whether it be Rotenier, Ackermann, or Brehmer, all those who teach jewellery illustration insist everyone can become very skilled. All you need is your imagination, your hand, paper, and a pencil—and regular practice.

| TIPS AND RESOURCES |

|

A wide variety of resources are available to help you in the design process, such as:

Additionally, it is a good idea to keep a sketchpad with you at all times, and to take art classes that teach proportions, values, shadow, shading, and negative and positive space. |

Kate Hubley is owner of Montréal design house K8 Jewelry Concepts Bijoux. She is also a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA) and a 2015 Saul Bell Award recipient. Hubley can be reached at kate@k8jewelry.com.

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Soul-Carousel-spinning-diamonds-gemstones-Ring_Coronet-By-Reena.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/sketch.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Shelly-Purdy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/RRB214.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/01_Claudio_Pino.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/03_Claudio_Pino.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Designer-Reena-Ahluwalia.jpg

- www.learnjewelrydesign.org: https://www.learnjewelrydesign.org/

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/designs-little-sketchy/