Changing with the times

The road to Dallas, and subsequently India, began 28 years ago after a chance encounter between Barbuzzi and GSL co-founder, Andrew Tatarsky, at a north Toronto shopping mall. Tatarsky was working an antiques appraisal event when Barbuzzi stopped by. They quickly struck up a conversation and soon realized they had both attended St. Michael’s College School. An opening for a gemmologist at Tatarsky’s office led to the two working together, and it wasn’t long before they ventured off on their own to start what would later become GS Labs.

When the opportunity to take on a major U.S. chain as a client presented itself in 2003, Barbuzzi re-located to Texas. Three years later, the first of GSL’s offices in India opened its doors. All the company’s locations are certified against the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 9001:2000, Quality Management Systems.

The grading business has evolved greatly since 1985, when Barbuzzi and Tatarsky started out. In the last few years, however, it’s the development of gem-quality synthetic diamonds that has garnered a great deal of attention. Although there was some concern when coloured synthetics first came on the scene, the fact they were so vibrant in colour made them easy to pick out without too much trouble.

Colourless lab-grown diamonds, however, are a different story, with concerns over disclosure and maintaining consumer confidence being voiced even before they could be produced in any real quantity. It wasn’t long, however, before undisclosed stones were being discovered. First came IGI’s discovery in May of 600 colourless synthetics in a single parcel. A month later, the Gemological Institute of America’s (GIA’s) office in Hong Kong uncovered 10 more. In both cases, the stones were grown using chemical vapour deposition (CVD).

While Barbuzzi says vigilance is necessary, he quickly points out the chances of coming across a single undisclosed synthetic are pretty slim. All lab-created diamonds are Type IIa stones, which constitute less than three per cent of the total gem-quality diamonds in the world.

“The number of synthetic diamonds out there is minute compared to the millions of natural stones,” Barbuzzi explains. “Because of what’s happened in the last few months, however, I think everyone is more aware of what is going on, as well as more aware of whom they’re dealing with and the assurances they receive.”

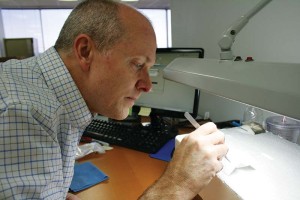

Although using advanced gemmological equipment is the only way to positively identify Type IIa diamonds, Barbuzzi points out there are a few things retailers can do. One, they can look at the stone under long-wave fluorescent light. He says synthetics tend to fluoresce green for the most part, as opposed to blue, as is the case of natural stones. Also, lab-grown diamonds created via high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) can sometimes include metallic flux inclusions that can be detected with the use of a simple magnet. Both methods do not conclusively determine a stone is lab-grown, but they may raise red flags. As Tatarsky puts it, “Your Spidey sense goes off and you look for other signs”¦ [But] I’m not sure all this is as scary as everyone makes it out to be. Synthetic coloured gemstones have been around for years. Eventually, science catches up”

Barbuzzi agrees, adding he predicts someone will develop a simple and inexpensive piece of equipment to positively identify synthetic diamonds in the next five years or so. His advice? Don’t panic and refrain from buying on the open market.