Does a gemstone’s country of origin matter?

by charlene_voisin | December 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Mark T. Cartwright

[1]

[1]How often have you had a client carefully explain the ring they just bought has a Burmese ruby, or a Colombian emerald, Paraiba tourmaline, or Russian alexandrite? How often have the gems in question struck you as being of fair quality at best? For me, these situations raise at least a couple of questions: Is it possible for me to positively determine the stone’s country of origin? Does the country of origin always/sometimes/rarely/never contribute to the value of the property? The answer to the first question is more tangible; the answer to the second can be more subjective.

Within some segments of the jewellery trade, it seems claims of country of origin are used as a selling tool that may also be intended to obfuscate a gemstone’s low quality. As valuers and gemmologists, it becomes a matter of reporting the facts as best we can determine them, without denigrating either the seller or the property. Sometimes it can be difficult to resist the temptation to at least smirk a little bit as one listens to the client repeat the extravagant tale that led them to purchase the item.

More than once I’m afraid I have failed miserably to conceal my dismay at the remarkable intersection of consumer ignorance and seller audacity. But tact aside, before dismissing the possibility, we need to be certain whether or not the seller’s claims of increased value were justified; in order to do that, we must first ascertain whether the gemstone’s country of origin can be verified. It should be noted from the outset that positive, conclusive determination of the country of origin is often impossible without the advanced instruments and an extensive reference database that only a few of the major laboratories can access. As always, we need to recognize and admit our limitations, while still doing all we can to solve the appraisal problem for the client.

Levels of competence

[2]

[2]This brings us to the realization that the science of gemmology is practiced at several levels of competency and sophistication. The training and background of the person performing the tests can significantly impact the credibility of the results. For example, even a skilled gemmologist with many years of trade experience may not recognize some subtle clues that would be evident to another skilled gemmologist with an advanced degree and years of experience working in a major laboratory. Similarly, a retail jeweller without gemmological education may miss evidence that a skilled gemmologist would readily recognize.

Unfortunately, the typical customer may not understand or be aware of the differences between various appraisers’ capabilities (leaving motivations aside). They will rely upon the appraisal results with equal confidence until a second, evidence-based opinion shakes their faith in the first report. I suspect most of us would rather be the author of the evidence-based opinion!

Obviously, the tests available to the gemmologist can also have a significant impact on a report’s credibility. Compared to the major gemmological laboratories, the vast majority of us are operating at a huge disadvantage in this regard. In many cases, even though the major labs’ tests are readily available, time and/or money restraints imposed by the client may prevent us from utilizing them. The Uniform Standards of Appraisal Practice (USPAP) offers us the following guidance from Standard Rule 7-2, Section (e):

Clearly, the issue of country of origin is an identifying characteristic that may be relevant and could have a material effect on value. If the limitations imposed by the client would prevent us from being able to provide an appraisal that is ‘worthy of belief,’ then according to USPAP and the codes of ethics for most appraisal organizations, we’re obliged to decline the assignment. Might the client simply go to another appraiser who would gladly issue a report? Possibly so, but the appraisal wouldn’t have our name on it and our reputations standing behind it.

Tools of the trade

[3]

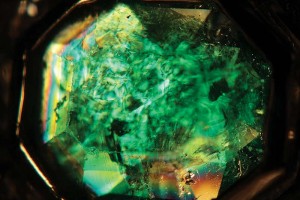

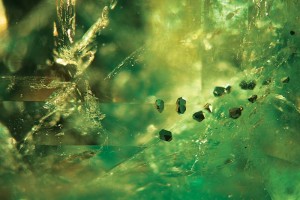

[3]It is hoped that anyone (i.e. everyone) performing jewellery appraisals has access to a precision binocular microscope capable of multiple modes of lighting and magnification up to at least 35X. If you are reading this and you don’t have access to this minimal testing ability, please invest in your professional future and your credibility. A quality gemmological microscope equipped to provide direct, dark-field, overhead, and fibre optic lighting is the most powerful tool most of us have when attempting to identify a gemstone’s country of origin. Equally important is the hands-on training and the reference library necessary to competently perform and interpret the tests. There are some determinations requiring additional equipment and testing, for instance, spectroscopic evidence of copper in Paraiba-type tourmaline, however, microscopic evidence is often our first line of exploration.

[4]

[4]Numerous organizations provide advanced training that can help us learn how and what to look for when examining gems with a microscope, as well as the proper use of other kinds of equipment. Sometimes, short courses are offered at trade shows, as well as conferences put on by many professional organizations. I often stress the importance of continuing education, and when it comes to confidently and competently recognizing the clues for country of origin determination, it is vital. I feel it is important to repeat that more often than not, given our limited equipment, we won’t be able to positively determine the country of origin for most gemstones. There are many wonderful books and computer programs that can offer us guidance, but for sheer beauty and comprehensiveness, I highly recommend the three-volume series, Photoatlas of Inclusions in Gemstones, as an essential set of references.

While the initial investment in texts, equipment, and training may seem daunting, it is critical to the successful identification of gemstones and their country of origin. In my experience, there have been numerous times when I was unable to determine exactly where a gemstone originated, but I was at least able to determine where it most likely did not come from. However, at the heart of the issue lies the question: when does a gemstone’s country of origin actually matter?

Value proposition

[5]

[5]The primary importance of a gemstone’s origin is the potential value difference between certain ‘historical’ sources and newer, less known sources. These historical sources for gems have become associated with an expectation of superior quality and greater rarity. The typical jewellery consumer is unlikely to be able to tell simply by looking whether a fine emerald is from Colombia or Zambia. Yet, they may be willing to pay a higher price for the stone with the ‘Colombian’ label, and only the Colombian label. The classification for emeralds, at least in the minds of consumers, seems to be ‘Colombian’ and ‘not Colombian.’ Similarly, the categories for ruby appear to be ‘Burmese’ and ‘not Burmese.’ The perceived value, especially for these two country of origin labels, has been accepted by some consumers to such a degree that even low-quality, heavily processed material finds a ready market if it comes with the right label. As appraisers, we need to recognize this market reality and conduct our value research accordingly. However, if the stone doesn’t meet the expectations of greater quality and rarity, then country of origin may not be an issue.

The unfortunate truth is that in lower qualities and with heavily processed stones, it may be impossible to determine the country of origin. Luckily, in general, when appraising lower-quality gemstones, the country of origin is primarily a marketing tool that doesn’t translate into a significant difference in value. On the other hand, if the gemstone in question is of fine quality and the potential value difference is significant, we need to do our best to convince our client that a report from a major laboratory is necessary to achieve an accurate valuation.

[6]

[6]This is especially true if the gem is a ruby or sapphire we believe to be untreated and of Burmese origin, since both factors are important value elements that should be documented. Third-party reports for emerald may not be quite as vital in every instance. The inclusions and growth characteristics of fine emeralds from Colombia are relatively diagnostic. When typical inclusions and growth features are present, the relative amount of ‘oil’ becomes the next important value element. If growth features and inclusions are absent from a fine-quality natural emerald, the expense of a lab report could be justified. The intended users of our reports rely on us to know when it is necessary or desirable to spend the time and money for a report from a major laboratory.

One of our biggest challenges is educating our clients, especially if our first impression is they’ve made a purchase based on naiveté and marginally ethical selling practices. The reality, however, is we may be hasty to judgment and they may be reluctant to accept our conclusions. A gemstone’s country of origin can be a powerful sales tool and it can also be a significant value element. Having the equipment and expertise to determine where a gem originated might be beyond the scope of our abilities, but we can learn to distinguish when it matters.

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/20-ct-aquarmarine-ring.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/9-ct-emerald-pendant.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Colombian-emerald-crossed-polarizers.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/emerald-oil-fluorescence.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/sapphire-and-diamond-bracelet.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Colombian-emerald-pyrite-inclusions.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Mark-Cartwright.jpg

- gemlab@cox-internet.com: mailto:gemlab@cox-internet.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/does-a-gemstones-country-of-origin-matter/