Esperanza: A diamond unlike any other

by jacquie_dealmeida | December 1, 2015 9:00 am

By Evert P. Botha

[1]

[1]“When I first saw and held Esperanza, it was smooth as silk and glowed like the moon. I don’t see a lot of rough diamonds, but I never knew they could look like she did!” ~ Laura Stanley, Stanley Jewelers Gemologist

A diamond like this only comes around once in a lifetime. Don’t get me wrong—my father, Mike Botha—has cut much larger diamonds in his career than this 8.52-carat stone, but Esperanza was exceptional. For starters, it is one of the biggest ever to come out of the ground at Arkansas’ Crater of Diamonds State Park, the world’s only public diamond mine and where visitors are allowed to keep anything they find.

I’ll never forget my first introduction to her at the Retail Jewelers Organization (RJO) Conference in St. Louis, Mo., in August. Jim Summa of Summa Jewelers in nearby Kirkwood handed Esperanza to me and I was speechless. Several certified gemmologist appraisers (CGAs) from American Gem Society (AGS) had already determined the stone to be a D-colour, and in all likelihood, IF-clarity, but let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Designing Esperanza

[2]

[2]When news broke in June a woman named Brooke Oskarson had found Esperanza, I contacted Laura Stanley, vice-president of Stanley Jewelers in North Little Rock, Ark., to try to track her down, hoping we could collaborate in some way. Meanwhile, Oskarson had reached out to Neil Beaty, a gemmologist based in Denver where she lives. We decided a collaboration could help ensure Esperanza’s provenance and provide a feel-good story at a time when the diamond industry desperately needed one.

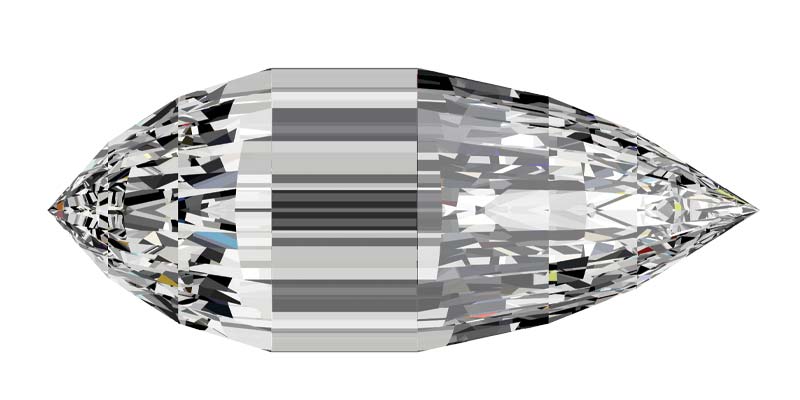

Once we’d committed to cut Esperanza, we immediately embarked on the design process. We knew right away we would not be satisfied to turn it into another emerald or pear-shape diamond. Its unusual origin made it special, so it had to be different. Our first thoughts were to cut a briolette; however, this shape doesn’t really return light, but rather reflects it. A diamond needs windows, which consist of crown facets to let light enter a stone. It also needs pavilion facets to allow light to be reflected back out through the table. A briolette fails in both these respects, as it only reflects light off the facets with very little light return.

Some years back, we prototyped a triolette, which is like a briolette, but in triangular form when viewed from the ends, much like a composite of emeralds and trapezoids tapering to a point on either tip. The advantage of this design is it returns light and maximizes the material. We initially designed Esperanza’s 147 facets using CAD software to test the various parameters of the cut and to do some ray tracing, which follows light from the point of entry to the point of exit.

[3]

[3]To maintain an American provenance, we committed to cut Esperanza in the United States, but before that could happen, Mike flew to AGS Laboratories to make the final decisions on the shape. By this time, the lab had already run spectroscopy analysis on Esperanza to determine its nitrogen content. The diamond proved to be a Type IIa with zero parts per million nitrogen content, an extremely rare find. A subsequent Raman spectroscopy test on the diamond showed zero parts per billion nitrogen content, which is off the scales! Under magnified polarized light, Esperanza was free of any inclusions that would possibly cause stress in the diamond. There was only a slight striatial observance of violet light absorption. This could have been due to some lamellar distortion, but only time would tell.

“When I learned about the low nitrogen content, I knew this diamond was going to be hard to cut—it was surely not going to be a marshmallow,” Mike said. Nitrogen in a diamond makes it easier to cut and polish, which is not the case in Type IIa diamonds, as they are pure crystallized carbon.

Planning Esperanza

[4]

[4]The crystal could best be described as an elongated dodecahedron—it had only one slight protrusion that defined one cube face (100) and one dodecahedral face (110).* There were no trigons, but there were three misshapen triangular protrusions with poor definition that indicated an approximate octahedral face (111). There were no visible inclusions in the diamond except for a very small cavity toward one of the points that only extended slightly into the stone. “When I saw the morphology of the crystal in person, it confirmed my initial perception that this should be a triolette design,” Mike said. “The diamond was more pointed at one end than the other, and the end view suited a triangular configuration way better than round.”

Using CAD software, Mike recreated Esperanza’s triolette design to establish precise angles and indices for the facets, an extremely tedious process in itself. By now, he had planned a blueprint of what the finished stone would look like. However, there was still one critical component to the puzzle that needed to be defined: the faceting sequence. He ran through many possibilities in his mind, reflecting on the approach he took with the previous triolette. After going through all the various iterations, he created the faceting sequence, which also allowed him to select the right equipment for the cutting process. Given the shape of the rough crystal, Mike decided to cut Esperanza as a whole, without any pieces sawn off.

Cutting and polishing Esperanza

Since it came out of the ground in Arkansas, there was no question Esperanza had to be cut there, specifically at Stanley Jewelers Gemologist in North Little Rock. It was also decided we would create an in-store event around the cutting process. From Sept. 9 to 12, Mike would cut the diamond at his bench, which we shipped from our home base in Prince Albert, Sask.

Sept. 8

Mike’s first task upon arriving at Stanley Jewelers was to study Esperanza to determine the exact location of its various crystal planes. After examining it, he decided to cut the initial facet close to the transition point between 100, 110, and 111. This meant one of the larger facets would be very close to 111, which is the hardest plane on a diamond, and on Esperanza, one that would come to haunt him later.

“Fortunately, I had about 1.5 degrees in my favour off this plane,” Mike notes. “First, I wanted to remove a protrusion to improve the possibility of clamping the diamond properly for cutting and to confirm the cutting direction. It also allowed me to create a window to look into the diamond.”

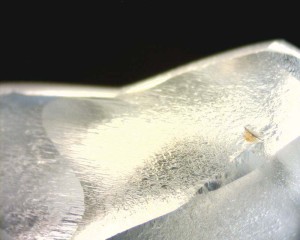

[5]

[5]Excluding the team at AGS Laboratories, no less than seven AGS-certified gemmologists and gemmologist appraisers had viewed Esperanza and could not find any inclusions. Note the tiny orange surface blemish on the right side of this photo. This was the only visible imperfection on Esperanza. In addition to shipping the polishing bench to Arkansas and all the tools Mike would need, we were fortunate to have a diamond scanner on hand to confirm the position of the first facet. Cutting a diamond’s first facet is a crucial part of the process, as it serves as the foundation or reference facet to which all the others will be inclined and indexed.

While cutting the subsequent facets, Mike juggled media interviews and photo sessions featuring Brooke Oskarson, the woman who had discovered Esperanza, as well as our hosts, the Stanley family. Not much work got done that day, but the atmosphere in the store was filled with awe and expectation. It seemed the whole of Arkansas was following what we were doing.

Sept. 9

Cutting started in earnest at 7 a.m. and Mike began by profiling Esperanza to establish the diamond’s precise outline. This is a complex procedure, as it involves checking and rechecking every detail. Imagine cutting three emeralds and six trapezoids in combination. If anyone thinks achieving an emerald cut is easy because it comprises straight lines, think again! Getting those lines absolutely parallel is the ultimate test of excellence in diamond polishing. Throughout the day, Mike answered questions and posed Esperanza for photos, as well as ensured the YouTube live stream we had set up kept about 2000 viewers from 95 countries engaged. Work continued throughout the day and finished at 6 p.m. for a total of 11 hours at the bench.

Sept. 10

[6]

[6]Employees from the Crater of Diamonds dropped by the store, bringing with them the legendary Strawn-Wagner, a diamond found at the mine in 1990 and considered one of the world’s most perfect cut diamonds. State officials and senior personnel also came to see Mike cut Esperanza, which starred in its own professional photo shoot and a mini-documentary filmed by the state of Arkansas. Throughout all this, Mike continued to work, albeit at a slower pace. By the end of the day, he had nearly completed the basic blocking.

Sept. 11

Mike was back at the bench at 7 a.m. This day saw fewer visitors and the work progressed at a much faster rate. Although we were aiming for a five-carat diamond, it soon became clear maintaining that threshold was going to be out of the question. The diamond weighed 5.01 carats by the end of the day and Mike had only just started polishing it. This is painstaking work, as every facet has to be polished to absolute perfection.

Sept. 12

This day was devoted to one of the larger primary facets, which took the better part of three hours to polish, as it was very close to plane 111. Work continued until 6 p.m. and by that time, Esperanza weighed 4.87 carats.

Sept. 13

Although we had anticipated being done by now, that would not be the case. Work progressed at a good pace, however, as there were no interruptions. Mike spent most of this day polishing the smaller facets, which resulted in losing .06 carats, now bringing the diamond to 4.81 carats.

Sept. 14

Work started at 7 a.m. and it was nose to the grinding wheel for the entire day, as Mike polished more facets. “This is by far the most beautiful diamond, yet also the hardest diamond I have cut in my entire career of 47 years,” Mike said. “What I expected to take around 40 hours was soon to be eclipsed by more than double that time.”

The afternoon saw a photographer from the local newspaper return to update readers on Mike’s progress. By this time, he’d already completed 105 of the 147 facets and the diamond was really starting to take on a life of its own. Work continued until 9 p.m. with a short supper break. By the end of the day, the diamond weighed 4.71 carats, with no less than 42 facets yet to be polished at its points.

Sept. 15

[7]

[7]This was to be a short day, as Mike was scheduled to return to Canada that afternoon. Although there was still some minor faceting to be done, Mike had cut enough of Esperanza to maintain its ‘Made in America’ provenance. He could finish the rest in Canada. The diamond now weighed 4.67 carats, and at that stage, we were confident it would finish in excess of 4.50 carats, which is pretty good considering the rough crystal’s shape.

After arriving in Prince Albert, Mike took a well-deserved break and work resumed again a day later. In between running the factory, he managed to complete the remaining 42 facets, bringing Esperanza to 4.625 carats. After some quality control and minor repair work, we decided she was ready to go to AGS Laboratories for grading.

A few days later, the lab confirmed Esperanza was internally flawless and colourless (D). There were, however, slight burn marks and minute facet misalignment on two junctions. The call was made to bring Esperanza back to our factory and aim for a flawless grading. Although some would question why we would attempt to attain this grade, Mike was adamant about wanting to give the best possible grade to one of the most unique diamonds ever discovered.

After two more days of intricate and painstaking work, we sent Esperanza back to AGS, a remarkable .002 carats lighter! However, some polish marks remained, which meant Esperanza returned to Prince Albert once again. Mike took his time on the last minor polish repairs, and we called in some GIA graduate gemmologists from Saskatchewan to assist with the final polish analysis.

At this article’s writing, Esperanza is once again at AGS for grading. We are hoping for the coveted flawless designation. If we don’t get it, we will be content with what is likely the most internally flawless, D-coloured triolette, which by most diamantaires’ standards, is sufficient in itself.

Esperanza will be presented to the public at a number of AGS retailers prior to going on the auction block in April. It will be set in a platinum pendant created by U.S. designer, Erica Courtney. As is, Esperanza is estimated to be worth at least $500,000 U.S., and that’s not taking into consideration its historical significance and all-American provenance. Whatever its final sale price, Brooke will receive 25 per cent as part of a consortium made up of ourselves, Stanley Jewelers Gemologist, and a silent investor. Not a bad return on the $8 U.S. cost of admission to the crater.

* Miller Indices is a notation system for describing a crystal face. See www.embeediatech.ca/miller-indices.

Evert P. Botha is chief operating officer (COO) of Embee Diamonds in Prince Albert, Sask., a family-owned atelier specializing in cutting and polishing high-performance diamonds. Botha can be reached via e-mail at ideal@embeediatech.ca[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Triolette-photoreal-image1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/copyrightcredit-Peter-Yantzer-AGS-Laboratories-Esperanza-with-convex-trigons1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_87291.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Esperanza.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/L001-20150729_1351261.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/L001-20150729_115222.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Early-in-cutting-process1.jpg

- ideal@embeediatech.ca: mailto:ideal@embeediatech.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/esperanza-a-diamond-unlike-any-other/