Going custom: A bright spot in a tough economy

How the ring was made

The best method for creating the garnet ring in our example was to cast the base mounting in 18-karat yellow gold and then fabricate a centre crown. Previously, I would have hand-carved a wax model for the base mounting. I have always enjoyed the hands-on challenge of wax carving and must admit, I was initially reluctant to use technology as an alternative. For the garnet ring, I used the store’s CAD/CAM system to lay out its dimensions and determine the melee placement. Stone layout can be very time-consuming, and using CAD is a great way to save many hours of labour. In this case, it helped to decrease the cost of the ring by several hundred dollars. Since the ring’s diamond setting was to be traditional, I refrained from using CAD or the mill to build the prongs or create the milgraining. Personally speaking, I still believe there are some things a machine can’t do as well as a bench jeweller’s hand.

After milling, I prepared the wax model for casting. To reduce the ring’s overall weight, I hollowed out the inside of the wax. Given a width of 13 mm, the ring would have weighed approximately 11 dwt had it not been hollowed out. I felt I needed to keep this ring at a finished weight of 7 to 8 dwt, otherwise it would have been too heavy to wear. When creating custom jewellery, we have to keep in mind not only the piece’s total cost, but also how comfortable it is to wear. A ladies’ ring cannot weigh half an ounce.

The rules for setting

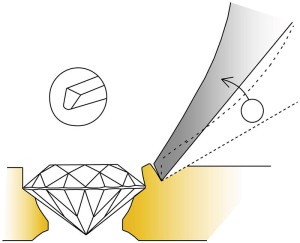

I tried to lay the groundwork for this series on creating custom-designed pieces in previous columns. I have already discussed in detail the process of preparing seats (see the June 2011 issue), but to refresh your memory, I drill pilot holes measuring half the stone’s diameter and then pre-cut the seats using an aggressive bur (i.e. round or bud) that is 90 per cent of its width.

Cutting the actual seats for the melee is a very exact procedure. The best advice I could ever give a new bench jeweller is to be precise when setting stones. I use a clean and sharp bur that is either exactly the stone’s size or slightly smaller. Never cut a seat that is larger than the stone’s diameter, as this will cause the gem to be loose and make the setting process much more difficult. If you do not have the correct-size bur, order one. Also, never use dull setting burs if you want perfect seats. Note how clean and sharp they are in the photo to the left. Seats should be cut to a depth that allows the stone’s table facet to be flush or slightly lower than the metal’s surface. Quality setting work has a 3-D look to it that cannot be duplicated by quick setting jobs.

Layout or planning work is critical for achieving a beautiful setting job. It is especially important in traditional four-prong, bead and bright setting. The stones in our example have been positioned so that a space of slightly more than half their diameter is between each of them. The only exception is end columns. Here, the stones are smaller so as to create a tapering effect. In order to keep the rows even, larger spaces were needed in the first and fifth lines.

In the photo above you’ll note the mounting has been coated with a thin layer of Chinese white paint. I’ve also drawn vertical lines down the ring. The space between the lines is where milgraining will eventually go. Milgraining needs to look proportional to the ring’s overall size. This is a big piece and thus, it will need heavy milgraining. With this design, I allowed half a millimetre of space between each row of diamonds.

The first cuts I make are always the frame or boarder lines, which define the seats. In our example, the frame lines also outline the eventual milgraining. For this work, I use a small onglette graver, which is typically wide enough so that it is sturdy and won’t chip easily. When doing fine or delicate work, I use a knife-edge graver instead. In either case, I don’t try to force the graver through the metal. The lines in the garnet ring were cut using several passes, each progressively deeper until I achieved the proper depth, which is equal to that of the stone’s seat. Be sure to hold the graver at an angle so that it creates a bevel facing toward the centre of the milgrain line. Note also the outside of the line cuts through the stone seat itself. The goal is to avoid leaving a thin ridge of metal on the sides of the seats.

Once all frame lines have been cut, including the bevel where the centre stone will go, it is time to begin isolating the prongs. For this process, I cleaned the ring and applied a new layer of Chinese white paint. Each stone will have four prongs, and I’ve drawn lines to mark where each cut will be made. I start at the centre of the space between two stones and cut at a diagonal toward the middle of the seat. This creates a four-sided diamond pattern between each stone seat.

Angling the graver toward the resulting centre of the diamond shape bevels its sides, creating a beautiful pyramid design.