Going custom: A bright spot in a tough economy

by charlene_voisin | February 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Tom Weishaar

[1]

[1]

Editor’s Note: This is the first instalment in a six-part series on creating custom jewellery. Over the course of the year, we’ll share the processes the author’s store went through to develop custom sales. We’ll also show you the methods used to create six custom pieces.

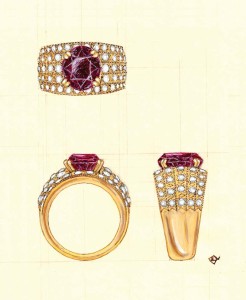

After trying on rings for half an hour, the customer pointed at one more. Placing the ring on her finger, she was convinced of the style and said, “This is the look for me! Only I want it bigger—big enough to be seen from across the room. I want at least five rows of diamonds. And since I was born in January, I want a garnet in the centre.”

How would you describe a custom client? Can we boil him or her down to just a few words and if so, what would they be? Would you say picky, unique, fun, worldly, crazy even? Over the years, I’ve dealt with customers who fit nicely into one or even two of these categories. There have even been a few who exhibited all these traits at the same time! The one common characteristic they all share, however, is they are not random in where they do business.

Custom clients are methodical about choosing the stores they shop at; likewise in picking the bench jewellers who create their jewellery. And most of their research is done through word of mouth. It can take years of hard work to develop a custom jewellery shop and a following of loyal customers. So guard your reputations and always deliver flawless service.

Show and tell

[2]

[2]In the store where I work, every display case contains several custom pieces. Each has a special blue tag, allowing the salesperson to instantly recognize it was made in-house. I think it is extremely important to be able to show clients the style and quality of work you can do. Simply put, you can’t sell custom if you can’t show custom.

We have a designer on staff with a background in art and, more importantly, a patient disposition. She meets with potential custom jewellery clients, gives them a tour of the store, and gets an idea of the type of piece they would like made. In the case of the female client who wanted a fancy garnet ring, she was first shown many styles of bands, including one I had made that she liked. It had three rows of diamonds set in a traditional four-prong, bead and bright-cut pattern.

Our designer is careful about writing down all the elements the customer says they want. Those notes, along with a few pencil sketches, are then refined into more deliberate drawings. We never want to offer the customer only a single solution. I think it’s best to present at least three different looks—one modest, one spot-on, and the final ‘stretch’ design. This last option is beyond the customer’s stated desires and budget. It’s a ‘wow’ design, and quite often, it’s the one the client can’t get out of his or her head and ends up selecting as the finished piece.

Bench jewellers should only get involved in the process after sketches are drawn up. Keep in mind that designers often do not have a jeweller’s depth of knowledge about how jewellery is made or what is even possible. After reviewing the sketches, I am able to discard designs that won’t work technically and keep the designer on track toward a piece that will look good and fit the customer’s needs. Use great caution here and choose your words carefully—this is usually the point where feelings get hurt.

Some customers are not nearly as easy to work with as our garnet ring client. Many take weeks to make their selection, which can make the designer’s job very time-consuming and even frustrating. This is why I do not recommend the bench jeweller be the person to meet with customers. Jewellers are typically very busy and aren’t usually allowed the time to develop the personal rapport with clients needed to coax their design vision for the piece.

[3]

[3]Once the three sketches are complete, it is my job to determine the final retail cost to create each piece. While I am busy with my estimates, the store’s gemmologist is tasked with locating and pricing out the perfect gemstones for the design. In the end, we all work together to create a package the designer can present to the client for approval.

Some of our customers live quite a distance from our store or have very busy lives. If it is inconvenient for them to return to meet with us, we often scan pictures and discuss any changes or issues over the telephone. I know some stores shy away from sending digital images to clients since they can then be taken to competitors to create the same item. However, we trust our clients, and we use every means possible to make their experience convenient and satisfying. Through a series of phone conversations and e-mails, our client settled on the ‘spot-on’ design seen in the photo to the left.

We all know the state of the economy over the past three years. The store I work for has also seen its share of slow days with few customers. For us, however, custom work has been one of the bright spots. While repair work has slowed in my shop, custom designing has soared. In years past, we averaged four or five custom-made items each month. During 2012, we averaged nine a month.

I have to warn you—getting into the custom design business is a slow process. It is built on your clients’ confidence in your work and their referrals, and it can just as easily be destroyed. There is an old saying of which I’m reminded: If you do one bad job, you kill 10 future sales.

How the ring was made

[4]

[4]The best method for creating the garnet ring in our example was to cast the base mounting in 18-karat yellow gold and then fabricate a centre crown. Previously, I would have hand-carved a wax model for the base mounting. I have always enjoyed the hands-on challenge of wax carving and must admit, I was initially reluctant to use technology as an alternative. For the garnet ring, I used the store’s CAD/CAM system to lay out its dimensions and determine the melee placement. Stone layout can be very time-consuming, and using CAD is a great way to save many hours of labour. In this case, it helped to decrease the cost of the ring by several hundred dollars. Since the ring’s diamond setting was to be traditional, I refrained from using CAD or the mill to build the prongs or create the milgraining. Personally speaking, I still believe there are some things a machine can’t do as well as a bench jeweller’s hand.

After milling, I prepared the wax model for casting. To reduce the ring’s overall weight, I hollowed out the inside of the wax. Given a width of 13 mm, the ring would have weighed approximately 11 dwt had it not been hollowed out. I felt I needed to keep this ring at a finished weight of 7 to 8 dwt, otherwise it would have been too heavy to wear. When creating custom jewellery, we have to keep in mind not only the piece’s total cost, but also how comfortable it is to wear. A ladies’ ring cannot weigh half an ounce.

The rules for setting

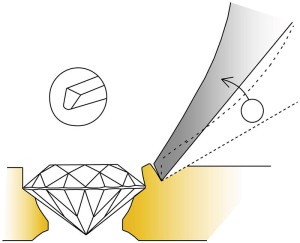

I tried to lay the groundwork for this series on creating custom-designed pieces in previous columns. I have already discussed in detail the process of preparing seats (see the June 2011 issue), but to refresh your memory, I drill pilot holes measuring half the stone’s diameter and then pre-cut the seats using an aggressive bur (i.e. round or bud) that is 90 per cent of its width.

[5]

[5]Cutting the actual seats for the melee is a very exact procedure. The best advice I could ever give a new bench jeweller is to be precise when setting stones. I use a clean and sharp bur that is either exactly the stone’s size or slightly smaller. Never cut a seat that is larger than the stone’s diameter, as this will cause the gem to be loose and make the setting process much more difficult. If you do not have the correct-size bur, order one. Also, never use dull setting burs if you want perfect seats. Note how clean and sharp they are in the photo to the left. Seats should be cut to a depth that allows the stone’s table facet to be flush or slightly lower than the metal’s surface. Quality setting work has a 3-D look to it that cannot be duplicated by quick setting jobs.

Layout or planning work is critical for achieving a beautiful setting job. It is especially important in traditional four-prong, bead and bright setting. The stones in our example have been positioned so that a space of slightly more than half their diameter is between each of them. The only exception is end columns. Here, the stones are smaller so as to create a tapering effect. In order to keep the rows even, larger spaces were needed in the first and fifth lines.

In the photo above you’ll note the mounting has been coated with a thin layer of Chinese white paint. I’ve also drawn vertical lines down the ring. The space between the lines is where milgraining will eventually go. Milgraining needs to look proportional to the ring’s overall size. This is a big piece and thus, it will need heavy milgraining. With this design, I allowed half a millimetre of space between each row of diamonds.

[6]

[6]The first cuts I make are always the frame or boarder lines, which define the seats. In our example, the frame lines also outline the eventual milgraining. For this work, I use a small onglette graver, which is typically wide enough so that it is sturdy and won’t chip easily. When doing fine or delicate work, I use a knife-edge graver instead. In either case, I don’t try to force the graver through the metal. The lines in the garnet ring were cut using several passes, each progressively deeper until I achieved the proper depth, which is equal to that of the stone’s seat. Be sure to hold the graver at an angle so that it creates a bevel facing toward the centre of the milgrain line. Note also the outside of the line cuts through the stone seat itself. The goal is to avoid leaving a thin ridge of metal on the sides of the seats.

Once all frame lines have been cut, including the bevel where the centre stone will go, it is time to begin isolating the prongs. For this process, I cleaned the ring and applied a new layer of Chinese white paint. Each stone will have four prongs, and I’ve drawn lines to mark where each cut will be made. I start at the centre of the space between two stones and cut at a diagonal toward the middle of the seat. This creates a four-sided diamond pattern between each stone seat.

Angling the graver toward the resulting centre of the diamond shape bevels its sides, creating a beautiful pyramid design.

The straight and narrow

[7]

[7]My advice is to make yourself very comfortable when cutting lines. Your arm, wrist, hand, and graver should all be in a natural straight line. I prefer cutting all the lines going in the same direction, one after the other. I then rotate the ring, get comfortable again, and cut in a new direction. Never force a cut from an unnatural position, since the graver is likely to slip and end up cutting a line across the piece. Also, remember to keep the graver razor sharp and polished, since a dull tool is likely to slip.

Sometimes the frame line does not intersect with the seat. When this happens, I use a small flat graver to remove the resulting sliver of metal. If I don’t, ugly fins of metal are created around prong beads. It is also easiest to remove them before the stones are in place.

I use a tool I call a ‘stone pusher’ to lock the diamond into its seat. Made of soft brass, it has a concave tip, much like a large beading tool. The pusher fits over the diamond’s table facet and forces the stone down into its seat. On round diamonds, I can push hard enough to actually embed the pavilion facets into the soft gold. This helps create an imprint of the stone in the metal, which in turn, keeps it tight after setting. A stone pusher is an easy tool to make. Brass can be purchased in most hobby shops or is available in jewellery tool catalogues as sprue formers. A handle from an old graver works nicely, but I prefer using one with a collet mounted on the end, which is also easily available.

Bringing it all together

[8]

[8]Once all 46 of the melee have been set, it is time to create the prongs for the centre stone. I have intentionally left a little bit more space above melee lines ‘two’ and ‘four’ to make room for the garnet’s prongs. This ring will not have an added crown; I want a look of unity, as though both the crown and the mounting were carved out of the same block of metal. I could have cast the prongs in place, but cast metal is not as dense or strong as pulled wire. By adding the fabricated wire for the centre crown, I am assured the prongs will be high quality.

All that is left to do is solder the prongs, set the centre stone, and do the milgraining. When possible, always solder from the inside of the ring where it is easy to clean excess flow. On the front, there should only be a neat ring of solder around the base of each prong that can be easily polished. For this project’s prongs, I used a good quality 18-karat yellow gold hard solder.

This ring was designed to have an old-fashioned look. Given its very traditional setting style, milgrain is a perfect addition to bring the whole piece together. I personally believe milgrain was originally invented to cover over mistakes, but I don’t know this for sure. I do know it has come in handy during times when my stone setting has been less than perfect. I’ve seen many bench jewellers make the error of not leaving enough space between diamonds for the milgrain tool to fit. For our example, I used a #10 milgrain tip, which needs approximately half a millimetre of space. When the seats are too close, you run the risk of the tool’s tip going over the stone and being damaged by the much harder diamonds.

Setting the centre garnet is turning out to be a simple job—this stone’s pavilion angles are close to that of a diamond. Therefore, it’s only a matter of using a regular setting bur to cut seats in the prongs. I will still take the time to check each prong and ensure there are no gaps or high points that could place uneven pressure on the stone and cause a chip. I am also careful to make sure the stone’s pavilion does not rest on the lower ring of milgrain defining the cut out. Resting a stone on a support is called ‘trapping.’ Often, the support ring will be visible through a poorly cut or windowed stone. This is one of the indicators of low-quality workmanship on the part of the stone setter.

[9]

[9]With fragile gemstones like garnet, I do as much finishing of the prongs as possible before I set. The last thing I want to do is accidentally scratch the stone with a steel file. The other benefit is that by tapering the prongs, I reduce the strength in their tips. This allows me to control the bend of the prong as it is pulled down onto the gemstone. I have accumulated many different Barrette needle files over the years. Each has been ground to a different thickness, some as thin as a business card, allowing me to work between prongs or get into other hard-to-reach places.

I was told the finished ring was a big hit. I wasn’t able to be there when it was presented to the customer, but that’s fine. As I said earlier, producing custom pieces needs to be a team effort. The important thing to keep in mind is we have to work together and not allow our individual egos get in the way of creating the perfect piece for the client.

Setting melee in this traditional four-bead style is a slow process. I can set between four and five stones per hour while maintaining a high level of quality. I estimate that by using CAD/CAM to help create the base mounting and lay out the gemstones, I saved five hours of labour. Overall, 18 hours went into creating this ring. The finished weight was 7.3 dwt. Since the ring is 13-mm wide at the top, we tapered the shank and rounded the inside edges. It was actually very comfortable to wear.

In the next issue, I’ll discuss the importance of staying current on the latest design trends and show how I made a fashionable bracelet using raw diamonds.

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[11].

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[11].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-01.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-021.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-03.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-051.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-09.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/B-B-illustration.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-11.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-13.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-18.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tom-Weishaar.jpg

- tweishaar@cox.net: mailto:tweishaar@cox.net

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/going-custom-a-bright-spot-in-a-tough-economy/