Going custom: How trend spotting can drum up custom work

by charlene_voisin | May 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Tom Weishaar

[1]

[1]

Editor’s Note: This is the second instalment in a six-part series on creating custom jewellery. Over the course of the year, we’ll share the processes the author’s store went through to develop custom sales. We’ll also show you the methods used to create six custom pieces.

Halos and micro-pavé have both been on the fashion charts for several years now and remain hot sellers for most jewellers. For the past two years, though, I’ve noticed raw diamond designs skyrocket in popularity. For me, these little opaque twinklers have been selling as fast as I can set them. As a custom jeweller, I try hard to keep pace with the current fashion trends. If I want to sell my work, I have to show a good selection of custom pieces in our display cases reflecting today’s hot fashions. Keeping up with fashion trends can be a quirky fast-paced proposition and nothing has been stranger than the current fascination with raw diamonds. Let’s take a look at this phenomenon.

In the diamond industry, a cutter trains by practicing his or her skills on opaque industrial diamonds. Once they’ve achieved the necessary level of expertise, they move on to better-quality diamonds. These practice stones, however, are typically recycled and made into abrasives. This tended to be their fate until someone came up with the idea of setting them into fashion jewellery. And voila—people started paying big bucks for these one-time cast-offs. Who would have thought this would be the case? In the past two years, my shop has created and sold more than 75 custom-made raw diamond pieces with a retail value of approximately $350,000.

Here’s another example of why it pays to keep up with fashion trends. Twelve years ago, designer jewellery with heavy engraving became very popular. At our store, we carried three different lines featuring various engraved patterns. We sold many of these pieces right out of the case, but not every customer wanted exactly what we had on display—many wanted the engraved look, but with their own design variations. Submitting special requests to a manufacturer is often problematic and sometimes impossible. However, we were getting so many requests for custom-engraved designs that I learned to hand engrave. Over the next five years, we produced more than 200 pieces. That’s over $1 million in hand-engraved custom jewellery. What’s the bottom line? It pays to keep up with trends and being able to incorporate them into custom pieces.

Creating a raw diamond bracelet

[2]

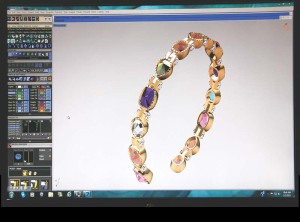

[2]The design in the photo to the right is the fourth bracelet I have made featuring raw diamonds. I created the first three by hand, as these orders happened during the time we were transitioning to CAD/CAM. Each of the links required two to three hours of labour just to carve the wax models. This fourth bracelet was made using CAD/CAM technology, which saved about 30 hours of labour.

Adding new technology raises a philosophical question: Do we charge our customers for the time saved using CAD/CAM technology or do we pass on the savings? The answer is not as simple as you might think. Look at it this way. The customers who bought the first three bracelets each paid for 30 hours of labour, therefore, why shouldn’t the fourth? Our store spent $30,000 on CAD/CAM technology. Don’t we have the right to recoup this investment? Is it fair to charge for the labour of a machine when I can do other profitable tasks at the same time?

I believe we need to answer these questions on an individual basis. I can tell you we have chosen to pass this labour savings on to our customers. In exchange, we are hoping for a larger volume of sales in return to help pay for the technology. I don’t know if the two are linked, but here is an interesting statistic. Prior to 2012 when much of our custom work was still being done by hand, my shop produced an average of four custom pieces per month. During all of that year, we used CAD/CAM almost exclusively and produced nine custom jobs per month. We are now so busy we have decided to hire another bench jeweller and have just invested in a wax growing machine. I will discuss that technology in the next issue.

I used a wax milling machine to carve the 15 links required for our bracelet project. The six links seen in the top left photo took three hours to mill. The great part about this technology is I can focus on other tasks while the mill is doing its job. My employer loves to see the mill carving wax models while we jewellers are at our benches working. For him, it’s akin to getting two projects done for the price of one. Personally, I do miss the intimacy associated with hand-carving wax models, but when it comes to carving 15 of the same thing, the mill is very practical.

Getting richer

[3]

[3]After casting the links in 18-karat yellow gold, I decided I wanted to brighten the metal so it looked more like pure gold. To do so, I strung the links on a platinum wire and heated them without using flux or deoxidizer. You can see in the photo to the left the links on the right side are now dark with oxidation. The heat has caused the copper within the alloy to congregate near the metal’s surface.

Soaking oxidized links in a 40 per cent nitric acid solution for about 20 minutes dissolves the surface layer of copper. I repeated this process a dozen times for our bracelet project. With each successive soaking, the links’ surface becomes a high-karat outer shell of near pure gold. This process is called ‘depletion gilding’ and has been used for centuries to give low-karat gold a richer appearance. On a side note: If I am ever having difficulty soldering an item, I often use an abbreviated version of this process to clean the metal. Well-cleaned metal solders much more easily than oxidized metal.

[4]

[4]Be careful, though. Always add pure acid to water. If you make the mistake of adding water to pure acid, you are likely to get a strong chemical reaction.

As you can see from the top left photo, the links’ surface is a bright, rich golden yellow; the metal almost glows with intensity. The only problem with depletion-gilded items is the metal cannot be polished, as doing so removes the outer shell of pure gold. You can, however, burnish the item if you want a shinier appearance. Polishing is not a problem for this bracelet, since the piece will have a hammered appearance in keeping with the look of the raw diamonds.

For a full description of how I made a tongue clasp for this bracelet, see the October 2012 issue of Jewellery Business.

Adding precision to rough appearance

[5]

[5]I am very fortunate my shop is well-equipped with a variety of unusual tools. One of my favourites is a circa-1940 Derbyshire watchmaker’s lathe. This piece of equipment is neither particularly rare nor is it expensive. After the Second World War, lathes like the one in the photo to the right were produced in the thousands and used by watchmakers to repair mechanical timepieces in the then-growing mechanical watch industry. Since the explosion of digital watches in the 1980s, however, lathes were no longer in demand and can now be purchased via Internet auction sites for a few hundred dollars. What makes them unusual is they are almost always regarded strictly as a watchmaker’s tool, and most bench jewellers have never been shown how to use one. With a little know-how and some practice, though, a bench jeweller can save many hours of labour and increase the quality of their work.

For our project, I used the lathe to create the threaded rivet dumbbells seen in the photo below. They will be used to connect each of the bracelet’s 15 yellow gold, raw diamond links. The rivets were designed in CAD, milled out of wax, and then cast in 18-karat white gold. The heavy main portion of the rivet is 2 mm in diameter and the threaded post is 1.2 mm. The outside end caps are each 4 mm in diameter and will be set with 1.6-mm round diamonds. All the finishing and stone-setting work was done using the watchmaker’s lathe. I’ll warn you ahead of time—stone-setting with a lathe is a lot of fun and very addictive. If you decide to invest in a lathe, you will look for ways to use it.

[6]

[6]Drilling a 6-mm long hole using a standard flex shaft is very difficult work. Pressure applied to the drill bit by your hand is uneven—even a slight twist of the wrist will break the drill bit. Drilling the same hole using a lathe is a simple task. I used one bit to drill out each of the 15 rivet bodies, making them into tubes.

Once all the rivet bodies were drilled, I used a 1.2-mm tap to cut threads on the inside of the tubes. Cutting threads is a laborious task requiring great patience. Taps this small are very easy to break. In this case, I used the lathe just to align the tube and tap. Rather than turning the lathe on, I gently hand-spun the tube one turn at a time, backing the tap out and cleaning it to cut the threads. Even though I was careful, I still managed to break two taps.

Threading the rivet’s posts was a much simpler task, requiring only a 1.2-mm adjustable die and a little patience. An adjustable die has an opening on one side and three screws on the outside of the holding tool, which are used to either spread or reduce the opening of the die’s centre. With the adjustments, I was able to make threaded posts that fit snuggly into the corresponding tubes. As I assembled the bracelet, I used a small amount of Loctite on the threads to hold them in place.

[7]

[7]I really enjoy bezel-setting stones with a lathe. As you can see in the photo to the right, I reversed the dumbbell’s orientation so the 4-mm outer end cap is now exposed in the headstock. The lathe’s tailstock has been fitted with a 1.6-mm setting bur. Cutting a stone seat into the end cap is quick work. It’s also simple to stop and check each seat to ensure the depth on all 15 is the same.

After cutting the seats, I placed .02-carat diamonds in the end caps and burnished them in place. There is a specific tool watchmakers used to burnish jewels into watch movements, but I don’t care for it. Instead, I use a large barrette file, one side of which has been highly polished. This allows me to get a firm grip and apply strong pressure to the spinning cap. I can roll the file’s edge over the seat’s outer lip and thus roll the metal right down over the stone’s girdle. This method helps me get a very clean and uniform bezel over the stone.

After setting the stone, I use a small pointed burnisher—the same one used to flush-set stones—to push the bezel’s inside rim down onto the diamond, sealing it in place. Once the stone has been set, the entire end cap can be polished while it spins in the lathe. Setting stones with a lathe is actually a fast procedure. I can generally set between five and six stones per hour. What I like best is the uniformity of the setting work. I also use this same method to set semi-precious stones, including opals.”¨It’s great for making tube-set earrings or pendants.

[8]

[8]Next, I turned to setting the 15 raw diamonds into their individual links. I’ve worked with CAD for a few years now and resolved many of the initial difficulties of sizing models to fit snuggly to gemstones. In the case of these raw diamonds, I projected an image of each stone onto a computer screen, using the diamond’s exact outline to create a model. I added a scant 0.05-mm to each stone to account for any shrinkage in the cast links. The result was that each stone fit very tightly into its individual custom link. Setting the raw diamonds became a simple matter of tapping the bezel’s inside lip down onto the stone and then applying a light brush finish to the metal to help blend in any tool marks. The only thing left now is to assemble the bracelet.

If you are curious, the small indentations going around the bezel are meant to resemble a crude form of milgraining. I think it helps to break up the design and adds a bit of a focal point.

The finished bracelet came out very nicely and was well received by its new owner. This 18-karat yellow and white gold piece turned out to be quite heavy at 24 dwts. It also took nearly a full week to create, coming in just shy of 40 hours. I was really glad I was able to use CAD/CAM technology and grateful for the 30 hours it saved me.

One last idea

[9]

[9]Custom jewellery can be both expensive and very personal. Your customers will understandably be proud of their new jewellery and want to show it off to friends who may also be able to afford nice jewellery. In the last year, we have been photographing our custom pieces in progress and then giving our customers a small photo album showing how their special piece was made. Each album has about a dozen pictures, and the description for each photo is usually just a few sentences long. So far, our customers have been very enthusiastic about their photo albums. We hope they will show them to their friends and each one will become a mini commercial for our store. Custom work is all about building your reputation one customer at a time.

Thank you for reading this article and all the others. I do enjoy your e-mailed comments or questions, so please keep them coming. In the next issue, I will discuss creating signature pieces and show you how I made a Victorian-style pendant using rose gold and pink diamonds.

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[11].

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[11].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Background-Opener-01.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-02.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-04.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-05.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-07.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-08.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-12.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-15.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-16.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tom-Weishaar.jpg

- tweishaar@cox.net: mailto:tweishaar@cox.net

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/going-custom-how-trend-spotting-can-drum-up-custom-work/