Going custom: Sign on the dotted line

by charlene_voisin | July 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Tom Weishaar

[1]

[1]

Editor’s Note: This is the third instalment in a six-part series on creating custom jewellery. Over the course of the year, we’ll share the processes the author’s store went through to develop custom sales. We’ll also show you the methods used to create six custom pieces.

[2]

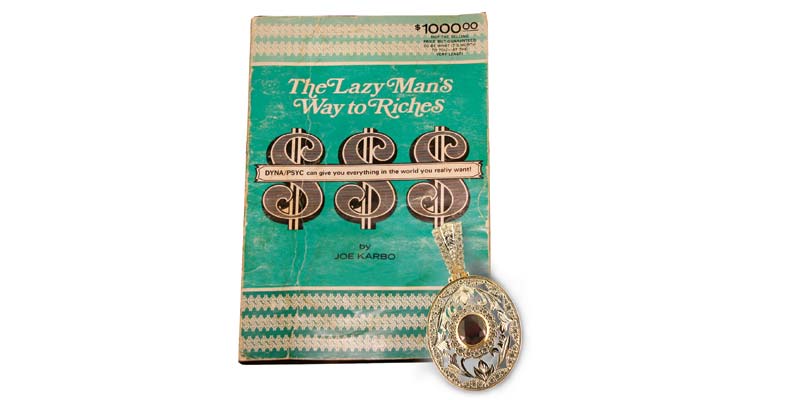

[2]Joe Karbo’s 1973 book, The Lazy Man’s Way to Riches, is about an ordinary man’s struggle to become a great salesman. In it, he dedicates his success to always trying to meet his customers’ needs. To this end, Karbo identifies the motivating factors for why people make significant purchases. Deemed the ‘4 Rs,’ they are: romance, recognition, reward, and reincarnation.

In my years as a custom bench jeweller, I have found the strongest of Karbo’s motivators to be reincarnation. Often, a reincarnation sale means I am rebuilding an older item that is being passed down through a family to be worn anew. These types of jobs are laden with emotion on the part of the client. How often has a customer come into your store with a piece of broken jewellery given to them by a relative who has passed on? I’ve heard customers say things like, “This is a very sentimental piece to me. I want it repaired no matter what the cost.”

This is just one type of reincarnation sale, what I call an ‘after-the-event’ order. The other type is the ‘before-the-event’ order. My favourite item to make is a ‘signature’ piece. The client who commissions a signature piece is looking to create a special item that will always be identified with them. Their intent is also to pass it on to a loved one down the road. When I make one of these special signature items, I always feel like I am creating a piece not only for my customer, but also for the next generation.

I mentioned in a previous column that 2012 was a very busy year for my shop; we had double the usual amount of custom jobs. In the months leading up to Christmas, I received orders for six large and expensive signature pieces. This many jobs at once is uncommon, and I’ve thought quite a bit about what may have caused this.

The power of an effective display

[3]

[3]Last June, a client commissioned the large Victorian-style pendant lying next to Karbo’s book on the first page. I was given a lot of latitude in its design, which meant incorporating a personal favourite of mine, filigree. The 14-karat white and yellow gold piece was to have a large oval ruby as its central focus and accented with many small white diamonds.

I finished the piece in early August, but the customer could not get into town to pick it up until October. In the meantime, my employer put the pendant on prominent display in one of our store’s wall showcases, suspending it from a spinning clock movement and using a large magnifying glass to show off the detail work. A saw frame and blade brought the display together, along with cards describing the piece and the tools used in its creation. At first, I was a bit embarrassed by this gaudy display, that is, until I saw the results. Every customer who came into the store stopped at the case to watch the pendant spin. It received so much attention that we got a second order for the same design from a customer who wanted one made as a Christmas gift for his wife. From that point on, our sales staff developed talking points about the display. It wasn’t long before we got a third order from yet another client.

The moral of this story is, enthusiasm drives sales. If you are a custom jeweller, it is important to show off your work and to educate your sales staff about how items are made. Excitement is contagious—our customers will want to purchase the items we are most motivated to sell. So don’t miss an opportunity to highlight a piece and sell it with passion.

Where possible, make it personal

Signature pieces are all about the customer. They are meant to be a celebration of the client’s life: their likes, successes, favourite colours, etc. Start by interviewing the customer to find out as much as you can about them. For instance, we used a ruby for the first pendant because the client was born in July. She also likes antique lace and is proud of her family name, hence the ‘S’ design we came up with for the back.”¨ In addition, the client wanted to wear the pendant on many different chains, including a strand of pearls.

Making a signature pendant

[4]

[4]By the beginning of December, I was starting to feel like I had conquered the majority of my custom work battles. I had one more large and complicated piece to make for Christmas and several smaller orders. That’s when my employer told me a fourth customer had placed an order for a signature pendant that had to be ready by Christmas. I was told the client lived in England and had seen the other three pendants on our Facebook page. Wow! That’s cool.

Over the years, I have hand-fabricated about a dozen pendants similar in design to these four; each of those previous jobs required approximately 60 hours of labour to complete. For our current projects, I used our store’s CAD/CAM system to help create them, saving nearly 30 hours of labour per pendant. I have a personal interest in highly detailed work, and the time savings generated by designing with CAD allowed me to spend a few extra hours fine-tuning the smaller details. The first of these four pendants—the ruby and diamond piece—was slightly criticized as looking rather flat. For the next three, I domed the front more to give them additional depth.

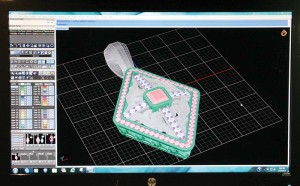

The pendant in the CAD image to the left was made using 18-karat rose gold set with pink diamonds and platinum set with white ones. This project also has the distinction of being the first job to be created using the store’s new 3-D printer, also called a wax growing machine.

There are many similarities between wax milling and wax growing technologies. For one, they are dramatically faster and can achieve a level of detail nearly impossible with hand carving. Additionally, both technologies leave a small amount of texture on the surface of finished models requiring a bit of hand finishing before casting.

It is the differences between milling and growing machines that might be more noteworthy. Growing machines make models about three times slower than milling machines, although they are able to create undercuts and hollowed out areas where mills can’t reach. Mills are slightly less expensive to purchase and can have a lower overall cost to operate and maintain. Mills use the regular carving waxes most bench jewellers are familiar with, while growers use specially formulated waxes that melt at tightly controlled temperatures. In a perfect shop, I would want to have both a mill for speed and a grower for detail.

[5]

[5]When we first investigated purchasing a 3-D printer, we heard stories about grown wax being difficult to cast. Specifically, the wax left a residue inside the flasks after burnout that could cause problems. I’m happy to report the problem has been addressed by manufacturers and grown waxes no longer leave any residue. In fact, they are as easy to cast as either carving or injection-type waxes. Note the beautifully cast pendant components in the photo to the right.

To solder the top two components, I lightly tacked the separate pieces together using a laser welder. The tacking was done from the inside, so that connection points are invisible from the front. It was also at this time that I tacked small pieces of white gold hard solder into the seam between the platinum and rose gold. The beauty of growers is the components fit so tightly together that only a speck of solder was needed to fill each seam. I always use white solder when joining white metals to other colours, as it tends to be less noticeable.

I used a different technique to solder the rear initial plate onto the back of the pendant. This time, I melted small chips of solder and flowed them onto the rim of the rose gold gallery. I used enough chips so that when the solder flowed into small pools, their edges touched each other. After quenching in pickle and cleaning in ultrasonic, I sanded the solder flat to remove any excess. This created the uniform rim of solder around the gallery’s top edge.

The process of coating a surface with solder is traditionally called tinning. The word comes from the old days when soldering was done with heavy iron rods that were heated and covered with molten tin. The tin could be kept liquid by the iron rod’s heat and then transferred to whatever needed to be soldered. Jewellers don’t use tin or iron rods for soldering, but I think the origin of our terminology is interesting.

[6]

[6]I placed the platinum initial plate over the solder and reheated everything using a large soft flame. The solder flowed a second time and was drawn up toward the hotter back plate. This process has traditionally been called ‘sweat soldering’ and was coined because jewellers gauge the heat of a piece by watching for flux to melt, pool, and then flow. Solder and flux both flow in similar temperature ranges; flux that looks like sweat is a good indicator the solder has also flowed. Be careful not to use too much flux or it will look like its crying, rather than sweating, bringing a tear to your eye when you see the messy results.

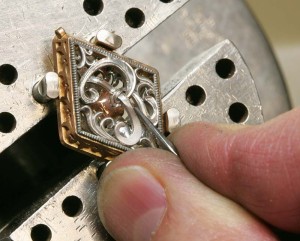

Assembling the enhancer-style bail seen in the photo to the left with its hinged rear opening, hinged pendant connection, and fold-over safety was one of the truly remarkable aspects of using the grower for this job. A platinum bail like this previously required a full day’s labour to create, along with up to a dozen soldering operations. Now with a grower, an item like this can be designed, grown, cast, and assembled in about two hours’ time.

For creating items like bails, growing machines can be a better alternative to milling operations. The bail in our pendant has many undercuts that are difficult for mills to produce. Mills also create bevelled cuts, which sometimes prevent pieces from fitting together without some additional hand finishing. For this grown bail, the pieces were lightly sanded and then snapped together. Even the hinge’s rivet pins fit snuggly in place without extra drilling. It was remarkable!

Icing the cake

[7]

[7]All the individual pieces in our pendant were pre-polished prior to being soldered. I think it’s very important to get as much of the heavy finishing work done before doing any surface embellishments or stone setting. I surely don’t want the hours of hand engraving to be worn down by coarse finishing work. Also, the finishing process is often the time when a pitted solder seam reveals itself. It’s best to illuminate any imperfections at this stage of the game. I want to ensure the piece is perfect before moving on to phase three of the project: hand engraving.

Hand engraving is one of my favourite things to do. I mentioned in the last issue that hand engraving became very popular about a dozen years ago. In order to keep up with my customer’s demands, I taught myself how to engrave. There are many books and several videos on the subject that helped me develop my skills. I now use air-pressure engraving tools to assist me. The photo to the right shows how I carved out the letter ‘R’ on the back of one of the pendants. I think every view of a piece of jewellery—front, side, and back—should be beautiful. I love to create items my customers will spend hours holding and discovering the small details I built into them. That’s when I feel I’ve done my job well.

[8]

[8]Even the front side of the enhancer bail was decorated with hand engraving. The pattern I placed on this bail is traditionally called ‘running leaf.’ My customers appreciate religious-themed jewellery, so I slightly altered the running leaf pattern to look more like two hands clasped in prayer. We also started referring to this engraving pattern as ‘praying hands.’ This one change sparked intense enthusiasm and ever since, I have created hundreds of pieces with the praying hands pattern. My best advice is to never pass up an opportunity to create imagery that speaks to your customers.

When I first began transitioning to CAD/CAM three years ago, it was tempting to quickly slam stones into seats and then move on to the next piece. At times I began to feel like I was on a jewellery assembly line and new pieces would arrive via a conveyor belt. I found it was possible to set as many as 20 stones per hour. It took some time for me to adopt a new attitude; this new technology is really only doing a portion of the rough work for me and I still need to perfect the piece by bright cutting and isolating the prongs. I now aim to set approximately eight stones per hour when using CAD/CAM.

As seen in the photo above, the pendant is mounted in plastic shellac and I’m using my onglette graver to trim excess metal from around each prong. I have previously discussed my bead- and bright-setting techniques, so I will not go into detail again. (See the February 2013 and June 2011 issues of Jewellery Business for complete discussions.) To enhance the pendant’s colour, I set the pink melee and the pink centre diamond in 18-karat rose gold. The same would be true for setting canary diamonds in yellow gold.

[9]

[9]The pink diamond seen in the photo to the right is from Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine in Australia. Unfortunately, this source is nearly depleted and the stones are no longer reliably available. We can occasionally order them from suppliers; sometimes, we even find recycled stones. The one-carat radiant-cut diamond we used for this job had been in our stock for a few years. A quantity of matched melee as shown in these photos is also difficult to find and very expensive. Pink diamonds tend to be heavily included, so I treated these with all the care I would show when setting expensive emeralds. The seat for the centre stone was hand-cut using flat gravers and the bezel carefully tapped down over the stone. Had I chipped this stone during setting, I could not have ordered a replacement and the pendant would have been ruined. The centre stone took nearly three hours to set. For the melee—which were not even close to being ideally cut—I slowed down from my normal pace of eight stones an hour and set only five stones in that time frame.

[10]

[10]Each of the four signature pendants weighed approximately 10 dwt. Three were made in platinum and 18-karat gold, while one was designed in 14-karat. Each required 35 hours of labour to complete, with an average retail value of $22,000 a piece, including the stones.

I hope you enjoyed this article on making signature pieces. As I was completing it, I found out a fifth pendant has been ordered. The next one will comprise sapphire and diamonds set in platinum and gold. Here we go again!

I don’t want anyone to think that making custom jewellery is simple and always turns out this well. In the next issue, I’ll tell you a story of a nightmare piece I was making at the same time as one of these pendants.

[11]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[12].

[11]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tweishaar@cox.net[12].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-01C.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-04.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Custom-Pend-03AB.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-05.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-07.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-11.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-12.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-14.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-15B.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Custom-Pend-16.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tom-Weishaar.jpg

- tweishaar@cox.net: mailto:tweishaar@cox.net

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/going-custom-sign-on-the-dotted-line/