Going custom: The road to success

by charlene_voisin | December 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Tom Weishaar

[1]

[1]

Editor’s Note: This is the fifth instalment in a six-part series on creating custom jewellery. Throughout the year, the author has shared the process his store went through to create custom pieces. This time, he turns his attention to a pavé diamond ring.

What I like best about Europe are the small towns with their narrow winding streets. Take this photo of a small village in France, for example. The homes all appear to have been built back in the 1800s. In a similar town, I met an old man who told me its cobblestone streets were 400 years old. Wow! The asphalt pavement where I live is a wreck after just 10 years. It’s no wonder the French have time to create such beautiful works of art and jewellery—they don’t spend it fixing their streets.

Please take a moment and really look at this beautiful street. The French use the word pavé to describe the cobblestone. In our industry, we have attempted to mimic their beauty by creating jewellery ‘paved’ with small diamonds. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could somehow get our pavé diamond jewellery to last 400 years? That would be a stretch, but if done well, a pavé ring should at least last a lifetime.

A star-studded ring

[2]

[2]Pavé is not a favourite setting style of mine. I actually find it to be quite stressful, as there is no room for error. The stones are supposed to be set very close together and the prongs are always shared between two and sometimes three gems. If you add to this mix randomly sized or poorly cut stones, then pavé setting jobs can easily turn into nightmares.

Recently, a husband and wife came into our store looking to have a ring to mark their 10th wedding anniversary. When asked if they would care to see our selection, the woman declined, saying they had a picture of the ring they wanted made. Turns out they had been watching a red carpet event prior to the Academy Awards, and the husband happened to take that moment to ask his wife what she would like for their anniversary. On the television screen flashed an image of a reality star showing off her new 10-carat engagement ring. Pointing to the screen, the wife answered her husband by saying, “I wouldn’t mind one of those.”

The very next day, the couple came into our store and brought with them the image you see to the right. The husband had snapped a photo of the television screen using his phone’s camera. The couple asked our sales associate if I could make a ring which would be similar in style, but with a smaller centre diamond and additional side stones. “Perhaps a four-carat diamond would do,” they said. Not a problem, we said, and I got straight to work.

Estimating costs and profits

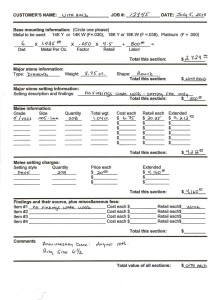

[3]

[3]The most frequent questions I receive are always about estimating costs and making a profit. There is not space in this article to fully address this topic, but I would like to share a few things I’ve learned over the years. It’s been my experience that a great many jewellers are unprofitable because they try to compensate for their lack of business skills by doing more volume. In my opinion, the absolute best practice is to do the opposite. In other words, reduce the amount of jewellery you make, stop discounting, increase quality, and maximize the profit from each job. In short, get organized.

Let’s look at the estimate sheet to the left for our pavé diamond ring. Forms like this are a fantastic way to help you get organized. (For a copy of this sheet, check out this article in the issue’s online edition.) At our store, we attach a copy of this form with every job file we do. It is also very helpful when updating appraisals. The more complicated the job, the more important the form.

I always begin an estimate by costing out the base mounting. Based on years of experience, I know the ring will weigh approximately 6 dwt of platinum. I record this on the form and then add the current cost-per-ounce for platinum, along with the ‘factor,’ which is indicated in parentheses on the sheet. Multiplying the ‘factor’ by the per-ounce cost gives you the metal’s spot price per dwt. In the case of gold, factor accounts for the metal’s karat. You can increase the factor you use if you want to consider what the metal supplier charges as its profit. Next, I add our store’s retail markup. (This number has to be individually suited to your store.) Finally, I input labour costs to create the mounting. This number includes considerations such as time spent designing, casting the metal, finishing the piece, and assembly. At my shop, we charge $100 per hour for labour. I know that may seem high, but it is the same hourly rate my car mechanic charges. You should also know the lion’s share of the labour charge goes to the store—I only wish I got it all.

Filling out the rest of the form is pretty straightforward when it comes to accounting for the retail value of the diamonds, findings, and setting fees. You should know that every item listed on the form has its own retail markup. We make a profit on everything. (I always recommend repair shops use their own findings and stones, as well as charge a reasonable markup on every item.)

In terms of stone-setting prices, it is very important for jewellers to know how long it takes to set stones. For this ring, I estimated setting five melee per hour, or $20 per stone (retail). I know it is possible to pavé-set faster than that, but speeding up the process only decreases quality, making it more likely a stone will fall out. On this, I refuse to compromise. I get these big jobs because my customers want quality. Using a form like this for every custom job and even complicated repairs can make it easy to account for your time and materials, helping your business be more profitable.

CAD/CAM to the rescue

[4]

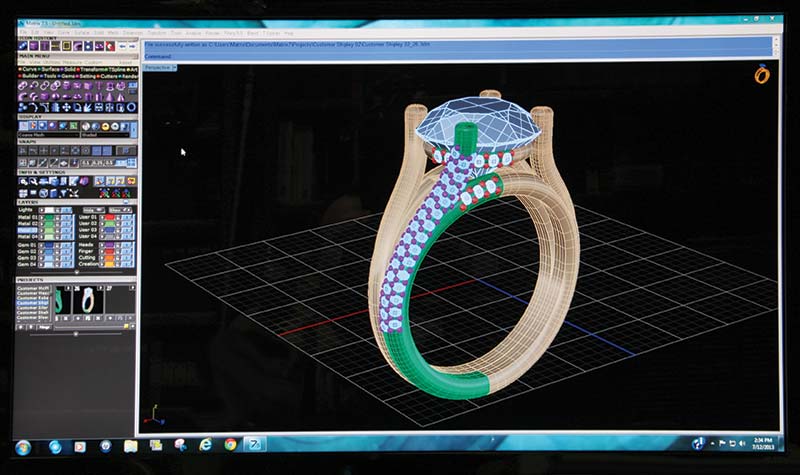

[4] [5]

[5]

Without the assistance of CAD technology to help lay out 208 melee and place the prongs, this ring could become a design nightmare. One of the great features of CAD is dealing with symmetry. Since the ring is perfectly symmetrical, I only had to design and place stones on one quarter of it. Using the software’s mirroring and copy tools, it became a simple matter of taking the finished section shown in green in the above photo and mirroring it into the other three quadrants. The ring took a total of just four hours to design. It would have taken much longer than that just to lay out the stones in one quadrant if I had done it by hand. Also, the results would not have been as good.

The before-and-after photos above show how beautifully a 3-D wax printer can produce a wax model and how well the platinum casting duplicated the details. Setting 208 diamonds into this ring would have been a tremendous task had it not been for both CAD and a grower.

Technology is wonderful, but it does not solve all our problems. The close-up photo below of the unfinished casting shows just how much hand work still remains. All the metal is in the correct places, but each seat still needs to be perfected. This mounting requires many hours of hand-finishing before a single diamond can be set.

[6]All the melee that went into this ring was ideally cut and of exceptional quality. It is routine for a jeweller to call a supplier and order the correct number of half-pointers needed for a job, but this practice doesn’t work well with pavé. When ordering melee by category (i.e. half-pointers), it’s not unusual to receive a mixed lot ranging in size. In this case, the stones would have measured from 0.90 mm to 1.10 mm. This is too large of a discrepancy for fine pavé work. Instead, I special ordered stones that were all exactly 1 mm in diameter. It took more than two weeks for the supplier to assemble the collection; we paid a premium, but it was worth it. I am not usually this fussy, but these stones were to be fitted girdle to girdle, and I did not want any of them to overlap and chip each other during the setting process.

[6]All the melee that went into this ring was ideally cut and of exceptional quality. It is routine for a jeweller to call a supplier and order the correct number of half-pointers needed for a job, but this practice doesn’t work well with pavé. When ordering melee by category (i.e. half-pointers), it’s not unusual to receive a mixed lot ranging in size. In this case, the stones would have measured from 0.90 mm to 1.10 mm. This is too large of a discrepancy for fine pavé work. Instead, I special ordered stones that were all exactly 1 mm in diameter. It took more than two weeks for the supplier to assemble the collection; we paid a premium, but it was worth it. I am not usually this fussy, but these stones were to be fitted girdle to girdle, and I did not want any of them to overlap and chip each other during the setting process.

My very first task was to bright-cut the metal between the stones’ seats. I used a 0.50-mm round bottom graver for this task. The graver had just been sharpened with my graver hone and then polished with a ceramic disc coated with diamond polishing liquid. The goal was not only to remove metal, but also to add a bright shine to the platinum.

[7]

[7]Using the graver to trim away the rough casting skin also left the prongs or beads uniform in size. This helped greatly when beading the tips, as it meant I did not have to switch out beading tools to accommodate different-size prongs.

As you can see in the photo to the right, every one of the ring’s four main legs was to be wrapped in pavé diamonds. Measuring 2 mm in diameter, each had four rows of stones. I first drilled the seats with a 0.50-mm drill bit. Since the melee is so tightly packed, I refrained from drilling all the way through the legs. This would have created azures and weakened the ring’s structure. Instead, I drilled small holes extending only a short distance into the legs.

Over the past few years, it has become very popular to place decorative cuts around prongs when setting single rows of melee. I personally like this look and have made it my practice, as well. I prefer using a very tiny onglet graver to create these scalloped cuts. Placing the graver at the centre base of the prong, I cut up and out toward the middle of each seat. I am careful not to remove any metal from the prong, as I will need it all to serve as two separate prongs.

After I’ve made all the scallop cuts and seats, I use a tiny self-made chisel to split the prong in two, right down the centre line, each half serving to set one stone. When doing this, be careful to lightly tap on the chisel with a hammer. Great care has to be taken or you might easily cut too deeply and weaken the prong.

[8]

[8]Setting work like this has to be done judiciously, as it does halve the overall size of the prongs. I personally will only do this style of setting in areas where the prongs are protected. In this case, that happened to be under the centre stone. Unfortunately, I often see this technique being used in areas where it is exposed to rough wear, resulting in stones falling out.

When pavé setting, I prefer to seat melee using a straight setting bur that is slightly smaller than the stone. The diamonds are set a bit deeper than normal, so more of the prong will be available above them to be used as tips. I then undercut with a 45-degree bearing bur. Since all the prongs on this ring are shared, I am extremely careful not to overcut them, as they will be weak and snap off.

Once a grouping of five or six stones is in place, I bead the prongs over them. A stone pusher may be necessary to ‘snap’ the melee into their seats. Properly beading prongs is extremely important and, unfortunately, many jewellers do not do a good job of it. There are more than 600 prongs tips on our ring and each one is rounded, polished, and free of snags. Your beading tool should be sized to fit snuggly and completely over the prong tip. If it is too small, it will squeeze excess metal out the sides and cause finning. On the other hand, if it is too big, it will not properly push the prong tip down onto the stones.

A beading tool can only burnish down 20 to 30 tips before it becomes rounded and worn out. I prefer using tiny carbide ball burs to reshape the beading tool’s concave tip every 20 prongs. Once the beading tip is sharp, the beader goes into the flex shaft and is spun on 1000-grit sandpaper to polish it inside and out. Notice in the photo above how clean and shiny each bead is—these tips have not been polished. (For a complete description of how to sharpen beading tools, please see Tom’s Tool Tip on page 50 of the June 2011 issue of Jewellery Business.)

[9]

[9]I was halfway through the process of setting the melee when our customers came by the store to check on their ring’s progress. My employer brought them into my shop and we sat for over an hour talking about how we were making the ring. I even tried to get the husband to set one of the melee, but he was too nervous. This couple was very excited about their ring and that enthusiasm is contagious. Customers who can buy an expensive ring have friends who can also afford nice jewellery. I’m sure that since this ring’s completion, the couple has been to several social events and told their friends what a great experience they had. To build your reputation and generate more custom sales, be sure to make your customers feel special by giving them excellent service and high-quality products.

Setting a four-carat high-quality diamond can be a nerve-wracking experience for any jeweller. The round diamond seen in the above photo costs much more than I can afford to replace. Even though diamonds are the hardest stone known, I treated this one as though it were a fragile emerald. As you can see in the photo, the mounting was designed so that the prongs overlapped the stone by one-third of their diameter. Those prongs are 1.8 mm wide at their tips, so I’ve got plenty of metal with which to work.

I used my favourite pair of calipers to mark where I wanted to cut seats in each prong tip. Note that marking the seats won’t ensure the cuts are perfectly level. I still prefer to place the centre stone and then hold the mounting up to the window above my bench. I’ve always felt the human eye can discern the smallest discrepancy—mine are my best level detectors.

There’s just got to be a better way

[10]

[10]In preparation for setting the centre diamond, I used a pair of chain nose pliers to spread each prong slightly out. I did this because I wanted a nice round ball of a prong tip over the stone and I knew I would have to undercut the seat in order to protect the tip. I began with a 45-degree bearing bur and cut individual seats in each prong. I have never been a fan of using a bur the same size as the stone and cutting all four prongs at once. Every time I’ve done so, the setting was crooked. After I initially cut the seats, I placed the stone in the mounting and checked to see if it was level. Once satisfied, it was a simple matter of using my graver to change the seat’s lower bearing angle so that it matched the diamond’s profile. I could have used a 70-degree or a 90-degree bearing bur and made quick work of the job, but I wanted to ensure I did not over cut the seats. I prefer doing expensive jobs by hand.

Placing the prong tips onto the stone turned out to be more difficult than I expected. These prongs are 1.8 mm in diameter at their tips; I could not get a good grip on them with my parrot pliers and the hammer tool was not strong enough to move the metal. Finally, I had to resort to using a hammer and chisel with a shallow cup cut into its tip. This is not a recommended practice, especially on a stone of this value, but I was desperate.

The finished ring turned out to be a big hit. Making fine jewellery like this is a pleasure. This is what we as bench jewellers dream of, and I feel very fortunate to be able to create these kinds of pieces.

My next article will complete this series on creating custom jewellery and I saved the best for last. In the December issue, I will tell you about my rare opportunity to hand-fabricate a fantastic three-stone platinum ring. Please join me then and, as always, thank you for your e-mails and comments.

[11]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tsweishaar@gmail.com[12]

[11]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tsweishaar@gmail.com[12]

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-Street-02.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-03.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-05.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-04.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-10.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-11.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-13.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-25.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-23.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Pave-26.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tom-Weishaar.jpg

- tsweishaar@gmail.com: mailto:tsweishaar@gmail.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/going-custom-the-road-to-success/