Into the blazing sunlight

Photos by Kyle Abram

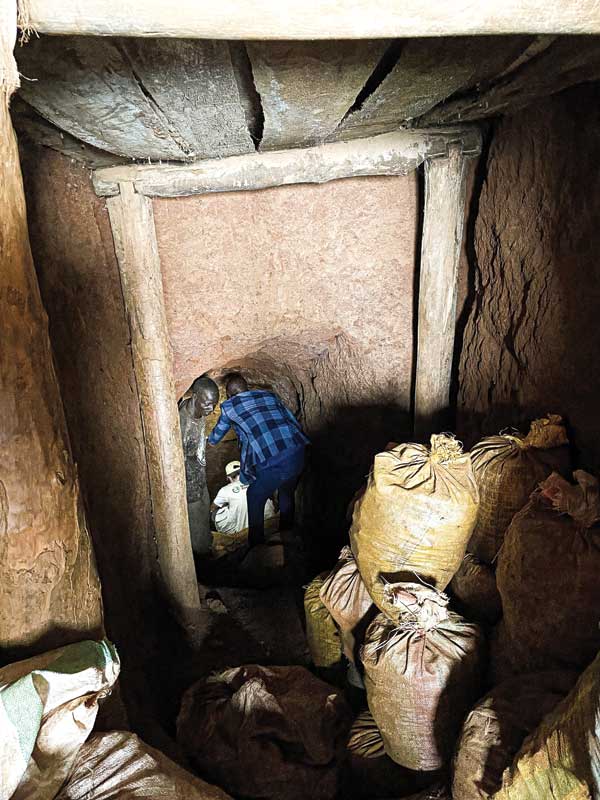

Several days after my journey to Mirundu, I visited another mine site supported by Zahabu Safi, this time in South Kivu province. Maybe it was the instant coffee I enjoyed that morning, but stepping onto the site, Luhihi, felt a bit like stepping out of the ‘Heart of Darkness’ and into the blazing sunlight—a representation of how mining conditions could improve if responsible sourcing were implemented to combat the exploitative status quo of the industry.

For one thing, I did not witness any child labour at the mine. Second, I personally observed miners extracting gold without the use of mercury (or any other toxic chemicals, for that matter).

I was shown how traceability measures are implemented and spoke with the woman in charge of monitoring site operations. In stark contrast to Mirundu, I was given every confidence this could represent a responsible supply chain. Luhihi demonstrated to me what a mine could look like after just a short period of engagement with Zahabu Safi, and the difference is measurable.

Still, immense challenges remain, including the substantial ongoing cost of monitoring for traceability. There are also considerations related to complications tied to consolidation and export, which all but require large-scale shipments. Perhaps most challenging, however, is there is little incentive for miners and traders to pay taxes on what had previously been tax-free.

None of this is insurmountable, but it does require breaking with Fairmined and Fairtrade in ways which are both philosophical and practical.

Zahabu Safi’s goal is to facilitate responsible sourcing for ASGM supply chain actors by providing financial and technical support to align sourcing practices with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance. The program uses risk identification and mitigation frameworks such as the CRAFT Code (among others), which is based on OECD guidance, and was developed by the Alliance for Responsible Mining—the same organization responsible for Fairmined. CRAFT provides immediate benefits to miners, but also entails a focus on ‘continuous improvement’—accepting processes won’t be perfect while also committing to operate responsibly and put plans and systems in place to work toward such a goal.

Central to this is the principle of ‘radical transparency’—meaning, the project is committed to acknowledging the realities in which small-scale miners live and work, as well as the setbacks and drawbacks that inherently arise within these environments.

A big part of why Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold has remained unscalable is the high cost and amount of labour involved in the capacity-building required to bring mines up to their standard.

“The irony of Fairtrade and Fairmined is they’re not fair,” Frampton says. “They prevent people from getting in because they set the bar too high.”

This high bar makes Fairmined and Fairtrade bulletproof against criticism of the labour and safety standards they uphold, as well as the community-building they facilitate. Further, it shuts out most small-scale mines and is particularly prohibitive to the smallest players, which produce less than a kilo a month.

In contrast, Zahabu Safi prioritizes access to responsible markets for miners through facilitated engagements with responsible buyers over imposing one specific due diligence framework or certification mechanism.

“Every buyer has their own due diligence processes, and these can serve either as a facilitator or a shackle, depending on how they are defined and implemented,” says Nikki Duncan, chief of party for Zahabu Safi. She tells me downstream actors have sometimes been so confused by the multitude of frameworks available, they forget due diligence is a means to an end—not an end unto itself.

“Due diligence is about demonstrating supply chain transparency with a view toward continuous improvement,” she says. “What we don’t want is for ‘perfect’ to be the enemy of the good—I can’t say it any better.” Flexibilité.

Indeed, Zahabu Safi aims to break the cycle of poverty and exploitation by facilitating market-viable and scalable solutions using a “market systems development approach.” Meaning, rather than directly subsidizing mining co-ops, it fosters enduring connections between different actors up and down the entire supply chain.

“We would do more harm than good if we just passed out cash and then stepped away,” Duncan says. “Success, for us, is measured by whether what we’ve set up sustains when we step away.”

For example, Zahabu Safi successfully partnered with two Congolese banks to offer (badly needed) pre-financing to mines under the project.

“Once our project ends, co-operatives will always be able to go the bank and, hopefully, get a loan—and not depend on a development program for something so critical to their business,” Duncan says.

Above all, Zahabu Safi aims to empower the Congolese to have a hand in their own fate. Duncan says the project is “…trying to minimize disruption to the market or undercutting of market actors.”

“We’re working with and through them, rather than replacing them… because, given this is Congolese project, Congolese people need to be at the forefront when it comes to determining what to do with these minerals,” she says.

Seeing this laid out clearly and hearing how sensible it sounds, it can be easy to mistake just how revolutionary a concept this really is.

Responsible gold revolutionaries

Of course, any revolutionary concept can sound great in theory; what remains to be seen is if someone can step up and see it through.

In 2020, Jason Clarke and Evariste Kikombe Emmanuel co-founded Society Artisanal with the aim of importing responsibly sourced gold from the DRC. Emmanuel, a Congolese native, originally brought the idea to Clarke. Both had previously developed multiple businesses, and, additionally, Clarke has more than a decade of experience working with refugees.

Society Artisanal’s goal is to implement a market-viable approach with transparent pricing structures able to serve as a positive development model (in other words: incorporate some of the basic ideas from Fairmined and Fairtrade but make it scalable).

Society Artisanal has agreed to export gold mined with the support of Zahabu Safi when it becomes available, but is working in the meantime to develop additional sources. Whether exporting from Zahabu Safi-supported mines or other sites they have partnered with directly, Society Artisanal will adhere to the CRAFT Code, be entirely mercury-free, and not allow child labour.

Clarke also tells me that, like Zahabu Safi, he and Emmanuel have a plan in place to set aside a percentage of sales for use on community development projects. Again, this is not unlike the models of Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold.

The problem of taxation, however, is a tricky one.

“If miners are making what they are today and then they go legal, they’ll be making less” Clarke says. “Why would they do that? They have zero incentive.”

The solution he offers is simple: partner with mining co-ops to bring in tools and equipment, and, in turn, increase production and profits. This win-win business model brings increased monetary value to miners while simultaneously funding Society Artisanal’s own continued operations.

The approach also provides the DRC’s government with a tax base where, previously, there was none—something Clarke tells me officials are, unsurprisingly, enthusiastic about. On a deeper philosophical level, of course, this is also literally empowering the people of the land to benefit from the resources of their land.

Society Artisanal has leveraged its team’s intimate knowledge of the DRC to make headway and is, according to Clarke, “very, very close” to making an export.

“We have chosen to do things in the most-strict fashion, which, in the DRC, is almost company suicide,” he says. “But, for this business and what this business will represent, it’s got to be done perfectly. We want to help change the market around gold.”

The model represents a dramatic departure from the thinking of Fairmined and Fairtrade: it’s aligned with Zahabu Safi, handles some very sticky problems, and is radically simple—maybe, just maybe, it will be able to break into the mainstream market.

Whether this can be achieved depends, unquestionably, on price. While Zahabu Safi’s goal is market viability, the program does not set prices, leaving this up to the supply chain actors themselves. While Clarke recognizes the importance of getting gold to jewellers at close to spot, Society Artisanal has yet to export.

The future of the market

Back in my second-storey New York apartment, with my moka pot heating on the stove and my cat on my lap, I think back to those miners at Mirundu and try to visualize all the others left unseen. Right now, millions of people across the Global South are toiling in economic slavery, living in desperate hand-to-mouth conditions, and poisoning themselves, their children, and the planet we all share, with mercury.

While Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold are inspirational and path-breaking initiatives, they have stalled and remain niche. Today, they impact just 0.01 per cent of small-scale gold miners—we owe it to the 99.99 per cent to try something new.

To reach the mainstream market, what is required are scalable, market-viable solutions. In creating a win-win business model (which is, by its nature self-sustaining and self-propagating, forgoing any reliance on benevolent of donors or guilty customers), Society Artisanal may have just cracked the code—with tremendous support from Zahabu Safi, I must add.

As we look to the future of the market, I urge anyone reading this to consider this fundamental question: what benefit might this bring to the miners, their communities, and their country?

The objectives of Zahabu Safi and Society Artisanal have been undertaken in the exact same revolutionary spirit as Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold—the difference is, today, they enjoy the benefits of 11 years of experience.

It’s just a matter of flexibilité.

Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry brand catalyst since 2017, is a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry. Abram, who served as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project, has appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference. He is also involved with Ethical Metalsmiths in multiple capacities, serving an editor/author for its blog, The Source, and on its Action Coalition. Abram is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition x GIA Distance Education Scholarship and holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com, or on LinkedIn.

Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry brand catalyst since 2017, is a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry. Abram, who served as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project, has appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference. He is also involved with Ethical Metalsmiths in multiple capacities, serving an editor/author for its blog, The Source, and on its Action Coalition. Abram is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition x GIA Distance Education Scholarship and holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com, or on LinkedIn.

Columnists’ opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Jewellery Business