Flexibilité: Clean gold from the ‘Heart of Darkness’?

by Samantha Ashenhurst | June 3, 2022 12:04 pm

[1]

[1]Photos by Kyle Abraham Bi

“The question is this: what benefit have you brought to the lives of miners?”

~Alan Frampton

By Kyle Abraham Bi

Editor’s note: In October 2021, Kyle Abraham Bi flew to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) as part of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) project, a model for the future of ethical gold sourcing from small-scale mines. Abram served as a representative for North American jewellers to the project, speaking extensively to many individuals involved with the various layers of the global endeavour.

I awoke under a mosquito net at 6 a.m. on a nearly bare mattress with several lizards and the largest spider I hope to ever lay eyes on staring at me from the walls of the inn. In this moment, I had but one wish: une petite sip of coffee from my beloved moka pot.

[2]

[2]Alas, there would be no coffee today—just another challenge added to an ever-growing list.

Just three days before, I had been a complete travel virgin, never having left the continental United States. Now, here I was, preparing for the final leg of my journey to a small-scale gold mine known as Mirundu.

“The theme of this trip will be ‘flexibility,’” a colleague had said to me as we soared over the Atlantic Ocean to Africa. While I didn’t fully appreciate this notion at the time, at the end of my two-week trip, I swore to her I would get the word tattooed on my flesh (in French, of course: flexibilité).

It was October 2021, and I was in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to serve as a representative for North American jewellers to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project[3]. Zahabu Safi, which means ‘clean gold’ in Swahili, represents a new model for folding responsible and traceable artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) into the jewellery supply chain. It is a significant departure from the existing models of Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold. (In the interest of full disclosure: the company I work for, Reflective Jewelry, has a Memorandum of Understanding [MoU] with Zahabu Safi.)

Within 15 minutes of setting off to Mirundu, it was clear my Zahabu Safi colleague and I were at an impasse (even though we had spent five hours travelling over dirt roads in our 4×4 SUV just one day prior). The rainy season had begun, and despite this being the main north/south route in the region, we clearly weren’t going to get any further on four wheels—it was time to pare down to two!

Within the hour, we had hired several young men to transport us on their motorbikes. The day had just begun.

The reality on the ground

[4]

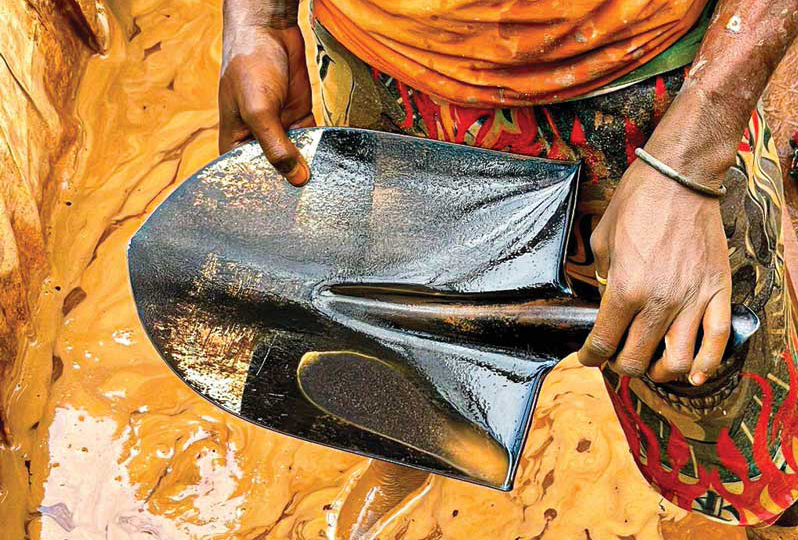

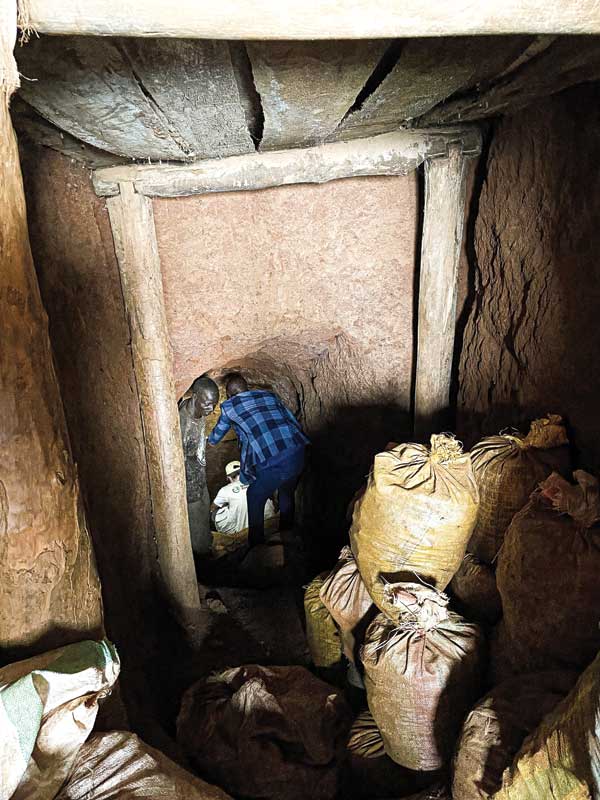

[4]Three hours and 70 kilometres later, we reach Mirundu. We were coated in mud that had flung from the tires of our motorbikes and clung to our clothing when we were forced to dismount and wade across bogs on foot. I looked around the site, struck by the bustling energy of the place—miners trekking up and down the mountain and the sound of shovels striking dirt.

Dressed in full safari attire (complete with cowboy hat and a broad smile), the landowner, Aimé (not his real name), enthusiastically shook my hand. My caffeine-withdrawal headache began to subside.

The tour Aimé provides is a window into the harsh realities of ASGM in remote areas of the DRC. Mirundu shows tremendous potential to reap the benefits of Zahabu Safi in the future. To have a willing landowner and local co-op structure in place are huge steps toward formalization/legalization that should not be taken lightly. As it stood on that day, however, the site provided a clear illustration of the challenges existing in the sector.

Take child labour, for instance. Dozens of the workers I observed appeared to be under the age of 18—many, perhaps, as young as seven- or eight-years-old.

“You have to understand the situation on the ground,” Aimé says. “Here, you’ll meet a 15-year-old boy who has two wives, or a 15-year-old girl who has two children… They have families to provide for, and, if their income is taken away, they will rebel.”

A blanket ban on child labour looks great on a sustainability report, but what is the real issue: that children are working, or that there is no alternative (i.e. no school within a 100-km radius)?

Of course, I also witnessed the expected specter of mercury use. ASGM is the world’s greatest single source of mercury pollution[5]. These miners—who handle mercury with their bare hands and breathe in supremely dangerous neurotoxins when burning it off—would need to be taught safer methods of gold extraction.

People living in a hand-to-mouth economy, however, aren’t typically willing to risk going hungry over alternative methods and, instead, stick to proven processes. What reason do miners have to trust outside entities warning of potential dangers (especially ones that aren’t immediately obvious)? Even if they are willing to give mercury-free alternatives a chance, there remains another barrier in the cost to switch methods.

The real tragedy, however, is the miners at Mirundu produce around 10 kilograms of gold per month, which is valued around US$600,000 (nearly Cdn$748,000). At the time of my visit, the site had been in operation for almost 18 months. This adds up to $11 million that could be—and should be—in this community. Where is it, though? Hidden in the mud brick walls of their homes? Doubtful, given they lacked even access to clean drinking water.

[6]

[6]Though this sort of mine is often demonized by the outside world, one can draw parallels between this and common misinterpretations of Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novel, Heart of Darkness. In this book, when Kurtz cries out, “The horror! The horror!” he is not referencing the jungle, nor its inhabitants; rather, his sudden revulsion stems from a realization of the animalistic greed of colonialists like himself and the abhorrent conditions unfolding under King Leopold II of Belgium[7].

Such horrors have echoed in the past century and a half, and are perpetuated today through what’s known as the ‘resource curse[8].’ The miners of Mirundu should not be demonized for the conditions in which they live and work. These conditions are a direct result of neocolonialist practices for which all those involved in the supply chain bear responsibility.

As a small example, consider that, despite the price of gold spiking during this 18-month period, the lives of these miners have not changed one bit.

Since 2011, however, there has existed at least one path to break to this chain in the form of Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold.

The irony of Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold

Fairmined currently supports 308 miners[9] across four mines: two in Peru and two in Colombia. According to the Fairtrade Foundation, there are an additional 1500 miners working at a total of 15 Fairtrade Gold-certified mines, all located in Peru.

Yet (although precise statistics are exceedingly difficult to ascertain), a 2017 report from the United Nations estimates there are roughly 10 to 15 million small-scale gold miners worldwide, including 4.5 million women and one million children[10]. This report also estimates as many as 100 million people worldwide depend, directly or indirectly, on small-scale gold mining for their livelihood.

Why, after 11 years, are there so few certified Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold mines—particularly when interest in ethical jewellery sourcing has seen such a dramatic uptick of late?

In search of an explanation, I reached out to Alan Frampton, the former owner of CRED Jewellery. Over many years, Frampton made dozens of trips to mines across South America and Africa, developing close relationships with communities and sorting out the challenging logistics of export and distribution. He essentially served as the keystone of the Fairtrade Gold movement for a time, supplying not only jewellers but major supply houses. As such, Frampton is held by many to be largely responsible for the success of Fairtrade Gold’s expansion beyond its initial formation.

[11]

[11]Photo courtesy Kyle Abram

“The question is this: what benefit have you brought to the lives of miners?” he asks. For Frampton, it’s not about labels, certifications, or how one can spin this to promote their own business; it’s about people and planet.

A few years back, Fairtrade Africa seemed poised to make breakthrough on gold, but this never materialized. Frampton told me that, after years of effort and investment, only one mine was ever certified. It was online for just six weeks before being de-certified—and he never received a “sensible answer” as to why this decision was made.

Additionally, he says, a Tanzanian site had once shown real promise. The mining organization made huge strides in implementing labour and safety standards and otherwise working to improve the lives of the miners. In the end, however, it didn’t fit into the Fairtrade structure, which meant it was never considered for certification.

Failures of Fairtrade Africa aside, Frampton was successful in organizing sizable imports of Fairtrade Gold from Peruvian sources. He regularly supplied his clients—including Reflective Jewelry, the only Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States[12]—at eight per cent over spot. This wasn’t a charity; it was a successful business model when run at scale.

Frampton was forced out of business in 2019 when his primary source was bought out by Valcambi and Fairtrade refused to send an auditor to a second sizable source (which had previously been certified). At the time, he personally offered to finance the expenses of the audit and a number of jewellers sent Fairtrade a petition on the matter.

“The deck is stacked against you,” Frampton says. “You’ve got consultants who run with the foxes and hunt with the hounds, you’ve got the Swiss refiners who are very clever corporate beasts… I genuinely thought I could take on the big boys.”

Unfortunately, the biggest losers in this story are the miners. When Valcambi began offering Fairtrade Gold for sale, Frampton says it was around 20 per cent over spot, which essentially killed the market.

“They’re getting more ‘social benefit’ than the miners!” he says.

Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold have, unquestionably, done a lot of good for a few thousand miners, but they have failed to provide a scalable, market-viable model that can significantly impact the mainstream market. As Frampton puts it, “How can you say it’s a success when nothing has changed in the past seven or eight years? It’s not a success if the movement isn’t growing.”

Into the blazing sunlight

[13]

[13]Photos by Kyle Abram

Several days after my journey to Mirundu, I visited another mine site supported by Zahabu Safi, this time in South Kivu province. Maybe it was the instant coffee I enjoyed that morning, but stepping onto the site, Luhihi, felt a bit like stepping out of the ‘Heart of Darkness’ and into the blazing sunlight—a representation of how mining conditions could improve if responsible sourcing were implemented to combat the exploitative status quo of the industry.

For one thing, I did not witness any child labour at the mine. Second, I personally observed miners extracting gold without the use of mercury (or any other toxic chemicals, for that matter).

I was shown how traceability measures are implemented and spoke with the woman in charge of monitoring site operations. In stark contrast to Mirundu, I was given every confidence this could represent a responsible supply chain. Luhihi demonstrated to me what a mine could look like after just a short period of engagement with Zahabu Safi, and the difference is measurable.

Still, immense challenges remain, including the substantial ongoing cost of monitoring for traceability. There are also considerations related to complications tied to consolidation and export, which all but require large-scale shipments. Perhaps most challenging, however, is there is little incentive for miners and traders to pay taxes on what had previously been tax-free.

None of this is insurmountable, but it does require breaking with Fairmined and Fairtrade in ways which are both philosophical and practical.

Zahabu Safi’s goal is to facilitate responsible sourcing for ASGM supply chain actors by providing financial and technical support to align sourcing practices with Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance[14]. The program uses risk identification and mitigation frameworks such as the CRAFT Code[15] (among others), which is based on OECD guidance, and was developed by the Alliance for Responsible Mining—the same organization responsible for Fairmined. CRAFT provides immediate benefits to miners, but also entails a focus on ‘continuous improvement’—accepting processes won’t be perfect while also committing to operate responsibly and put plans and systems in place to work toward such a goal.

Central to this is the principle of ‘radical transparency’—meaning, the project is committed to acknowledging the realities in which small-scale miners live and work, as well as the setbacks and drawbacks that inherently arise within these environments[16].

A big part of why Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold has remained unscalable is the high cost and amount of labour involved in the capacity-building required to bring mines up to their standard.

“The irony of Fairtrade and Fairmined is they’re not fair,” Frampton says. “They prevent people from getting in because they set the bar too high.”

[17]

[17]This high bar makes Fairmined and Fairtrade bulletproof against criticism of the labour and safety standards they uphold, as well as the community-building they facilitate. Further, it shuts out most small-scale mines and is particularly prohibitive to the smallest players, which produce less than a kilo a month.

In contrast, Zahabu Safi prioritizes access to responsible markets for miners through facilitated engagements with responsible buyers over imposing one specific due diligence framework or certification mechanism.

“Every buyer has their own due diligence processes, and these can serve either as a facilitator or a shackle, depending on how they are defined and implemented,” says Nikki Duncan, chief of party for Zahabu Safi. She tells me downstream actors have sometimes been so confused by the multitude of frameworks available, they forget due diligence is a means to an end—not an end unto itself.

“Due diligence is about demonstrating supply chain transparency with a view toward continuous improvement,” she says. “What we don’t want is for ‘perfect’ to be the enemy of the good—I can’t say it any better.” Flexibilité.

Indeed, Zahabu Safi aims to break the cycle of poverty and exploitation by facilitating market-viable and scalable solutions using a “market systems development approach.” Meaning, rather than directly subsidizing mining co-ops, it fosters enduring connections between different actors up and down the entire supply chain.

“We would do more harm than good if we just passed out cash and then stepped away,” Duncan says. “Success, for us, is measured by whether what we’ve set up sustains when we step away.”

For example, Zahabu Safi successfully partnered with two Congolese banks to offer (badly needed) pre-financing to mines under the project.

“Once our project ends, co-operatives will always be able to go the bank and, hopefully, get a loan—and not depend on a development program for something so critical to their business,” Duncan says.

Above all, Zahabu Safi aims to empower the Congolese to have a hand in their own fate. Duncan says the project is “…trying to minimize disruption to the market or undercutting of market actors.”

“We’re working with and through them, rather than replacing them… because, given this is Congolese project, Congolese people need to be at the forefront when it comes to determining what to do with these minerals,” she says.

Seeing this laid out clearly and hearing how sensible it sounds, it can be easy to mistake just how revolutionary a concept this really is.

Responsible gold revolutionaries

[18]

[18]Of course, any revolutionary concept can sound great in theory; what remains to be seen is if someone can step up and see it through.

In 2020, Jason Clarke and Evariste Kikombe Emmanuel co-founded Society Artisanal[19] with the aim of importing responsibly sourced gold from the DRC. Emmanuel, a Congolese native, originally brought the idea to Clarke. Both had previously developed multiple businesses, and, additionally, Clarke has more than a decade of experience working with refugees.

Society Artisanal’s goal is to implement a market-viable approach with transparent pricing structures able to serve as a positive development model (in other words: incorporate some of the basic ideas from Fairmined and Fairtrade but make it scalable).

Society Artisanal has agreed to export gold mined with the support of Zahabu Safi when it becomes available, but is working in the meantime to develop additional sources. Whether exporting from Zahabu Safi-supported mines or other sites they have partnered with directly, Society Artisanal will adhere to the CRAFT Code, be entirely mercury-free, and not allow child labour.

Clarke also tells me that, like Zahabu Safi, he and Emmanuel have a plan in place to set aside a percentage of sales for use on community development projects. Again, this is not unlike the models of Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold.

The problem of taxation, however, is a tricky one.

“If miners are making what they are today and then they go legal, they’ll be making less” Clarke says. “Why would they do that? They have zero incentive.”

The solution he offers is simple: partner with mining co-ops to bring in tools and equipment, and, in turn, increase production and profits. This win-win business model brings increased monetary value to miners while simultaneously funding Society Artisanal’s own continued operations.

The approach also provides the DRC’s government with a tax base where, previously, there was none—something Clarke tells me officials are, unsurprisingly, enthusiastic about. On a deeper philosophical level, of course, this is also literally empowering the people of the land to benefit from the resources of their land.

Society Artisanal has leveraged its team’s intimate knowledge of the DRC to make headway and is, according to Clarke, “very, very close” to making an export.

“We have chosen to do things in the most-strict fashion, which, in the DRC, is almost company suicide,” he says. “But, for this business and what this business will represent, it’s got to be done perfectly. We want to help change the market around gold.”

[20]

[20]The model represents a dramatic departure from the thinking of Fairmined and Fairtrade: it’s aligned with Zahabu Safi, handles some very sticky problems, and is radically simple—maybe, just maybe, it will be able to break into the mainstream market.

Whether this can be achieved depends, unquestionably, on price. While Zahabu Safi’s goal is market viability, the program does not set prices, leaving this up to the supply chain actors themselves. While Clarke recognizes the importance of getting gold to jewellers at close to spot, Society Artisanal has yet to export.

The future of the market

Back in my second-storey New York apartment, with my moka pot heating on the stove and my cat on my lap, I think back to those miners at Mirundu and try to visualize all the others left unseen. Right now, millions of people across the Global South are toiling in economic slavery, living in desperate hand-to-mouth conditions, and poisoning themselves, their children, and the planet we all share, with mercury.

While Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold are inspirational and path-breaking initiatives, they have stalled and remain niche. Today, they impact just 0.01 per cent of small-scale gold miners—we owe it to the 99.99 per cent to try something new.

To reach the mainstream market, what is required are scalable, market-viable solutions. In creating a win-win business model (which is, by its nature self-sustaining and self-propagating, forgoing any reliance on benevolent of donors or guilty customers), Society Artisanal may have just cracked the code—with tremendous support from Zahabu Safi, I must add.

As we look to the future of the market, I urge anyone reading this to consider this fundamental question: what benefit might this bring to the miners, their communities, and their country?

The objectives of Zahabu Safi and Society Artisanal have been undertaken in the exact same revolutionary spirit as Fairmined and Fairtrade Gold—the difference is, today, they enjoy the benefits of 11 years of experience.

It’s just a matter of flexibilité.

[21]Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry[22] brand catalyst since 2017, is a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry[23]. Abram, who served as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project[24], has appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference. He is also involved with Ethical Metalsmiths in multiple capacities, serving an editor/author for its blog, The Source, and on its Action Coalition. Abram is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition x GIA Distance Education Scholarship and holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com[25], or on LinkedIn.

[21]Kyle Abraham Bi (formerly: Kyle Abram), Reflective Jewelry[22] brand catalyst since 2017, is a signatory of 2020’s BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry[23]. Abram, who served as a representative for North American jewellers to the USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project[24], has appeared as a featured speaker at the Chicago Responsible Jewelry Conference. He is also involved with Ethical Metalsmiths in multiple capacities, serving an editor/author for its blog, The Source, and on its Action Coalition. Abram is an inaugural recipient of the Black in Jewelry Coalition x GIA Distance Education Scholarship and holds a BA from Brown University in Contemplative Studies. He can be reached at kyle@reflectivejewelry.com[25], or on LinkedIn.

Columnists’ opinions do not necessarily reflect those of Jewellery Business

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/opener-the-question-is-this.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/crop_before-heading-to-mirundu.jpg

- United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project: https://www.land-links.org/project/zahabu-safi-commercially-viable-conflict-free-gold-project-cvcfg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-Mirundu-mine_.jpg

- single source of mercury pollution: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/chemicals-waste/what-we-do/mercury/global-mercury-assessment

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/On-the-way-to-Mirundu_.jpg

- abhorrent conditions unfolding under King Leopold II of Belgium: https://bit.ly/36SxNao

- resource curse: https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/nrgi_Resource-Curse.pdf

- Fairmined currently supports 308 miners: https://fairmined.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Fairmined-premium-report-ENG.pdf

- including 4.5 million women and one million children: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/21725/global_mercury.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/The-author-center.jpg

- the only Fairtrade Gold jeweller in the United States: https://reflectivejewelry.com/ethical-sources/fairtrade-gold

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/A-boy-sorts_.jpg

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Due Diligence Guidance: https://www.oecd.org/corporate/mne/mining.htm

- CRAFT Code: https://www.craftmines.org/en

- the setbacks and drawbacks that inherently arise within these environments: https://www.wired.com/2007/04/wired40-ceo

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/inside-a-mine-shaft.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/A-simple-rug-system_.jpg

- Society Artisanal: https://societyartisanal.com

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/A-worker-at-Luhihi.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Abram_headshot.jpg

- Reflective Jewelry: https://reflectivejewelry.com/

- BIPOC Open Letter to the jewellery industry: https://bipocopenletter.com/

- USAID Zahabu Safi (Clean Gold) Project: https://www.levinsources.com/what-we-do/zahabu-safi-gold-drc

- kyle@reflectivejewelry.com: mailto:kyle@reflectivejewelry.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/gold-may-2022/