By Dorothée Rosen

The topic of sustainability is a minefield, and almost as tough to manoeuvre. Yet, it is crucial to stay informed so you can provide discerning customers with accurate answers. For example, due to free trade agreements between the European Union (EU) and Canada, you might be asked relevant industry-related questions on socioeconomic events occurring on the other side of the pond. Would you know what to say if a customer asks you about the EU’s new ban on greenwashing and the use of misleading environmental claims?1 You could reply with, “Only sustainability labels based on official certification schemes or established by public authorities will be allowed in the EU.” You could also tell them about how carbon footprint claims are treated similarly: “The directive will ban claims that a product has a neutral, reduced or positive impact on the environment because of emissions offsetting schemes.”

With an increasingly better educated public, remaining informed about industry-specific definitions in this realm has become a vital selling point to positioning yourself as a trusted authority. One prominent area of discussion that we in the industry must make ourselves aware of is ‘recycled gold.’ Let’s dive into the term.

Supply

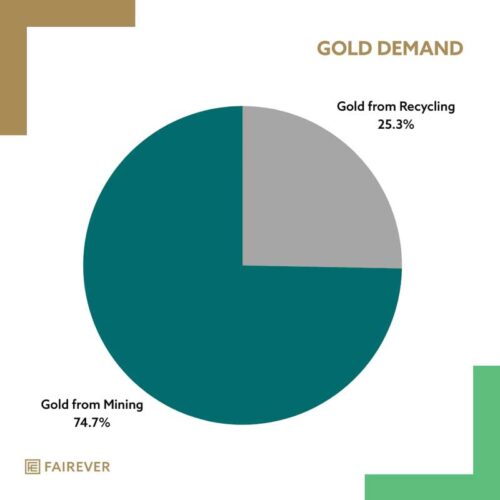

Even though so much gold has already been mined, most of it is sitting in banks. The annual demand for this precious metal cannot be met by recycling alone. In the first quarter of 2024, central banks worldwide bought more gold than they had in any previous quarter. Consequently, more gold must be mined to meet demand.

In 2023, 3644.4 tonnes of gold were retrieved from mines. According to the World Gold Council, (WGC)2 only 1237.3 tonnes, or roughly 25 per cent of the worldwide demand for gold, were covered by recycled gold.

So, what exactly is recycled gold?

The Oxford Reference Dictionary defines recycling as “The reprocessing of discarded waste materials for reuse.” People often associate recycling with the words ‘environmentally friendly,” What comes to mind might be aluminum cans or glass bottles, emptied of their content, and reprocessed into brand new bottles. This saves raw materials and avoids additional waste going into landfills.

Gold, of course, would never end up in landfills (except in minute amounts from electronics that have not been disposed of properly). Especially not now, with gold prices at an all-time high!

Therefore, the use of the word ‘recycled’ in connection with gold is extremely misleading.

Changing the definition of ‘recycled gold’

There is no question that customers are becoming increasingly more discerning about where the precious metals used in creating their jewellery comes from. With this, the demand for recycled gold is increasing.

This trend has even encouraged the Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) to consider adding investment gold (bullion or gold bars) under the term ‘recycled gold.’ As the journey from mine to bar is brief, this would further water down the definition of ‘recycled gold.’

There is strong opposition to the RJC’s change in definition. Organizations such as The Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM), The Precious Metals Impact Forum, Ethical Metalsmiths, and others are protesting this proposal.

These voices oppose the RJC’s proposed definition of “recycled,” stating it deviates from established legal and normative definitions of recycling. Instead, they recommend adopting a definition consistent with international standards, limiting the term “recycled” to products with very little recoverable gold (e.g. e-waste—less than two per cent gold in the alloy). Whereas products that contain more than two per cent gold (e.g. old jewellery, dental scrap, bullion) and for which the gold was recovered, refined, or just melted and reused could be designated as “reprocessed precious metals.”

Additionally, ARM has submitted an open letter to RJC with detailed arguments regarding the risks of greenwashing associated with definitions not aligned with legal standards and public expectations of the word “recycled.”

Conflict gold, money laundering, and child labour

The definition of “recycled” is only one problem. The other is the origin of this gold. As exposed in the documentary “The Shadow of Gold,”3 this precious metal is one of the easiest ways to launder money.

For example, a study conducted by the Swiss non-profit organization SWISSAID in 2020 shows that a large proportion of the gold sold to Germany via Switzerland as recycled gold originates from the United Arab Emirates.4 The controls in Dubai regarding the origin of purchased gold are demonstrably inadequate. Further, when gold is imported from the Congo and transferred to France, France is considered the country of origin.

The study concluded illegal gold from conflict areas ends up in the international gold trade without any problems. It then enters the market as ‘recycled gold.’ Therefore, naming such gold as ‘ethical’ would be problematic.

Not even e-waste gold, which truly is recycled, is ethical. Several reports show more than 18 million children between the ages of five and 17 are employed in the industry, working on tasks including the processing of e-waste.5,6

Child labour can only be ruled out with 100 per cent traceability, and traceability is at the front of organizations such as Fairtrade and Fairmined.

Useful resources:

• Canadian supplier of traced ethical Diamonds: Vantyghem Diamonds |

Alternatives and solutions

What if a goldsmithing studio refines and re-melts precious metals in their shop in-house, is that more ethical? Better? Yes. But the term “recycling” should be used with caution. It could instead be called “sustainably repurposing precious metals.” Since the original source of the clients’ gold is unknown, calling re-purposed gold ‘ethical’ is still problematic.

You can ask your suppliers what due diligence they take to be certain of the origin of their precious metals. Do they have published, detailed, and certified chain of custody practices in place? Are their recycled precious metals third-party verified?

You also have the option to make and/or sell products made with verified gold from smallscale artisanal mining. As my colleagues Marc Choyt and Kyle Abraham Bi pointed out in the May 2023 issue of Jewellery Business, buying Fairmined or FairTrade gold is by far the best alternative.

This is the best option for your store if sustainability and ethical practices are a main selling point, especially as no other gold can be guaranteed to be 100 per cent child-labour-free. Fairmined in particular has excellent marketing support to educate your customers and let them feel a personal connection to the people on the other end of the supply chain.

If you have the kind of customers who care, or soon will care, about such topics, be sure to do your homework and use sustainability terminology appropriately.

References

1 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/2024

0112IPR16772/meps-adopt-new-law-banning-greenwashing-and-misleading-product-information

2 https://www.gold.org/goldhub/data/gold-demand-by-country

3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BE35NEijhb0&theme

4 https://www.swissaid.ch/en/articles/the-dark-side-of-the-gold-trade/

5 https://www.who.int/news/item/15-06-2021-soaring-e-waste-affects-the-health-of-millions-of-children-who-warns

6 https://www.unicef.org/media/129446/file/Children_and_E-waste_Key_Messages_2022.pdf