How experience and close observation can save you money

By Hemdeep Patel

Every day, we use our five senses to observe and interact with the world around us. In most cases, the interaction is passive. Take the simple act of driving down the street—we use our eyes to see the traffic around us and our hands and feet to manoeuvre the car safely.

If you were to place a professional race car driver behind the wheel, they would likely perceive their surroundings in a completely different way. For instance, they would feel any slight change in the tire pressure through the steering wheel; their eyes would inform them about traffic conditions four or five cars ahead; and their ears would be able to tell them how well the engine is running.

While the scenario might be the same, it is the way in which the senses have been trained to manage and observe the environment that differs. This was a lesson I learned early in my professional life, and am reminded of every day.

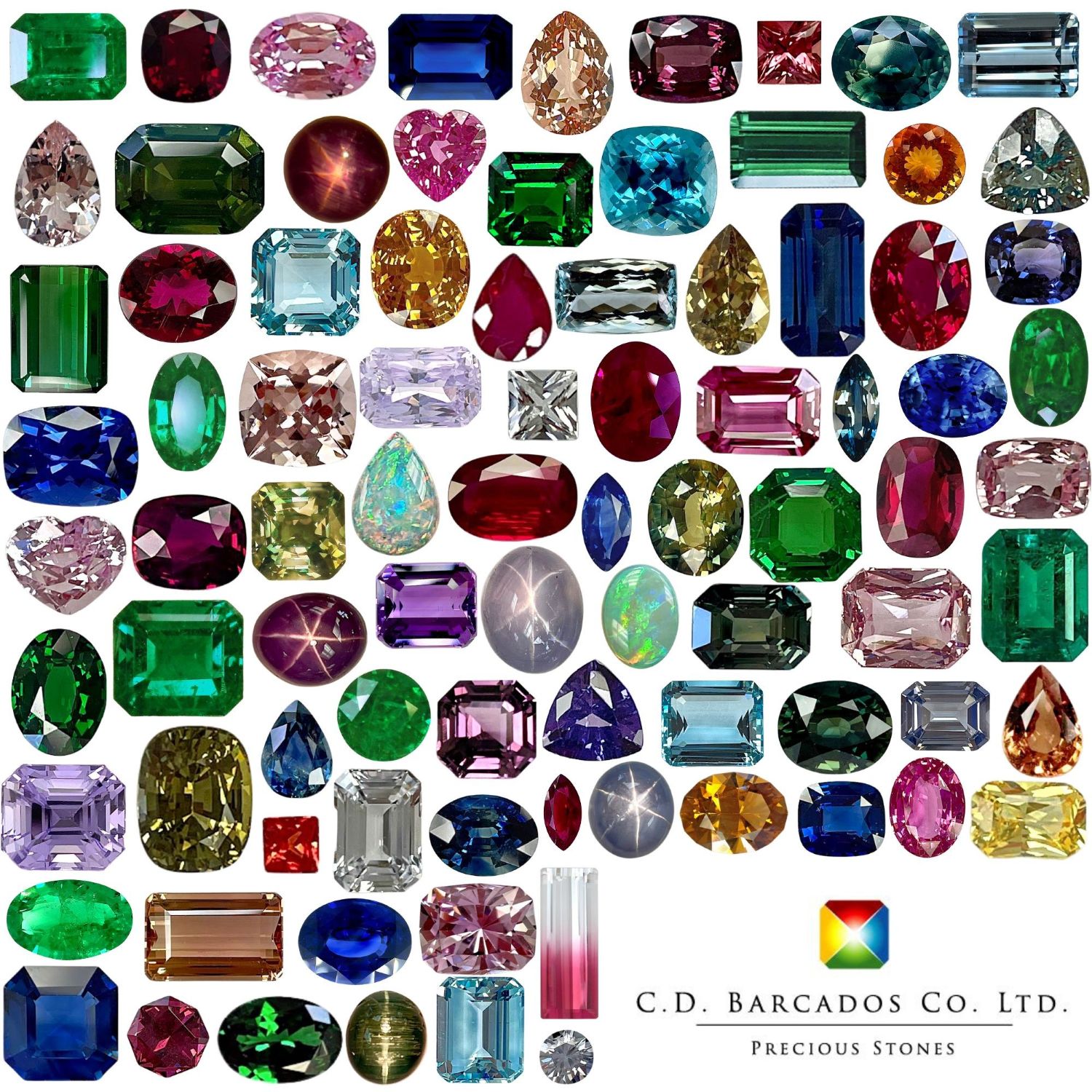

Experience and keen perception are a must in the jewellery industry. Since the scale of the object is most often very small, this is a good place to start training the eyes to see things that can truly make a difference in value and price. These differences range from the obvious, such as a diamond’s grade as described by its clarity and colour, to factors impacting price that are not overtly explicit but which are learned through experience.