How unethical practices in the global diamond industry affect you

by charlene_voisin | February 1, 2015 9:00 am

By Alan Martin

[1]

[1]

Why should the Canadian jewellery industry care about ethical challenges in the diamond supply that largely occur elsewhere in the world?

It’s a common question industry members ask me, many of whom feel insulated from the vulnerabilities of faraway and less stable or less governed jurisdictions.

With the rare exception of cases like last February’s arrest of a woman smuggling 10,000 diamonds through Pearson airport in Toronto, this is largely true.

Yet, while the Canadian industry—from miners through to manufacturers and retailers—may not directly contend with many of the reputational threats facing artisanal diamond producers in Africa or major trading centres like Antwerp or Dubai, they nonetheless share an industry. Reputational harm done elsewhere reverberates through the supply chain, sparking consumer concern and possible negative economic damage.

All that glitters

[2]

[2]This certainly was the case a few years ago when violence in the Marange diamond fields of eastern Zimbabwe led the Kimberley Process (KP), the international initiative that regulates the trade of rough diamonds, to impose an embargo on stones from the area.

Although not a classic case of conflict diamonds—”¨as the perpetrators of the violence were state actors not rebel groups—the Canadian government rightly took a tough line, as much for ethical reasons as to protect the economic bottom line of our own industry, ranked within the top five globally in terms of both value and production.

Since the KP’s formation more than a decade ago, the ethical landscape has shifted considerably. The most obvious example is the way in which new forms of violence by state actors are affecting the diamond sector, challenging the outdated and rebel-based definition the KP uses to determine what constitutes a conflict diamond.

A decade ago, issues like revenue transparency, environmental degradation, formalization of artisanal miners, terrorism financing, or transfer pricing in trading zones were hardly talked about in the diamond world. Yet, as these issues are widely debated in initiatives dedicated to improved and more responsible sourcing of other precious minerals, it was only a matter of time before the discussion caught up with the diamond world.

The last issue, transfer pricing, was a major focus of a Partnership Africa Canada (PAC) report, “All That Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals[3],” and one gathering growing attention from African governments that are failing to realize the full economic potential of their diamond resources. (Transfer pricing happens when two companies that are part of the same multinational group trade with each other.)

What are the reasons for this discrepancy and what are the consequences of this to Africa’s diamond-producing countries? In 2013 alone, price manipulations due to transfer pricing generated in excess of $1.6 billion in profits for diamond companies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and represent a major deprivation for African treasuries, which lost much-needed tax revenues that could have funded public services.

In the Congolese diamond context, transfer pricing cost the treasury an estimated $66.2 million in 2013. Perhaps one of the worst affected countries is Zimbabwe, where an average 50 per cent undervaluation of its diamond exports to UAE resulted in an estimated $770 million bypassing revenue authorities between 2008 and 2012.

Zeroing in on terrorist financing

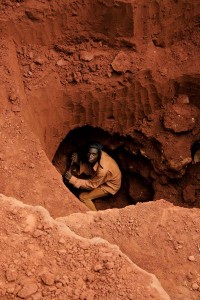

[4]

[4]of their diamond resources.

PAC is not alone in its concern. Last year, a joint report by the African Development Bank (AfDB) and Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a U.S. research and advocacy group, concluded the illicit hemorrhage of resources from Africa is about four times its current external debt—or as much as $1.4 trillion between 1980 and 2009.

As South Africa’s ambassador to the United States pointed out on a panel we recently shared, this theft of Africa’s potential is largely the work of commercial interests headquartered outside the continent and action has to be taken in those jurisdictions to end this practice.

For the international law enforcement community, this activity spells a concern of a different kind.

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Egmont Group are two of the world’s leading agencies studying the issue of money laundering and terrorism financing. In 2013, they published a seminal study looking at the intersection between those threats and the diamond industry. Many KP members took part in the study, from North America to southern Africa, from Europe to the Middle East.

It makes for some stark reading, not least of which are its conclusions on the issue of transfer pricing in Dubai. Take for example the following excerpt: “Diamond trade centres like Dubai, which operate as free trade zones (FTZs), are susceptible to money-laundering vulnerabilities”¦This, in combination with the specific vulnerabilities of the diamond trade and the mechanism of transfer pricing, creates a significant vulnerability for money-laundering and terrorism-financing activities.” Â

As the report notes, by way of over- or under-invoicing with affiliate diamond companies located in free trade zones, it is possible to illegitimately shift profits from diamond companies in high-tax rate countries to FTZs and thus avoid taxes. The combination of a lack of transparency in the diamond trade with a lack of transparency in a free trade zone provides an excellent atmosphere to conduct large-volume transactions without being detected.

The report makes several recommendations, specifically targeting identified and proven vulnerabilities of the Kimberley Process. They cover everything from how to improve certification and enforcement to the lack of transparency and documentation by industry members.

The KP has yet to respond—never mind seriously discuss—this report’s findings. The response by most industry groups has been equally disappointing and dismissive. During the World Diamond Congress in Antwerp last June, most participants were largely ignorant of the report’s existence. By and large, and with a few exceptions outside of the big miners, some would argue the industry does a poor job of keeping abreast of, and proactively responding to, emerging threats. There is also a naïve belief the KP does everything it is supposed to do to protect the diamond trade.

Raising the bar

[5]

[5]The Canadian industry is not exempt from FATF’s and Egmont’s findings or the issue of transfer pricing, and let me tell you why: for the same reason that conflict-affected diamonds from Marange tainted the integrity of the global diamond industry. Dodgy business in one jurisdiction has a knock-on effect throughout the supply chain, particularly among increasingly aware consumers brought up on a litany of ethical products from fair trade coffee to textiles. Reputational risks undermine confidence in the diamond sector and that is not in anyone’s best interests. Consumers matter, but even more so do banks, many of them who are either leaving the diamond sector altogether or imposing stricter lending requirements to placate internal concerns about risks associated with the diamond world.

The good news is that PAC, industry groups in the United States and Europe, and a growing number of governments are working to improve responsible sourcing and trading practices in the diamond sector, similar to due diligence requirements Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) helped to create for other conflict-affected minerals.

While Canada may be a modest player in the global manufacturing and jewellery sectors, our diamond deposits make us an acknowledged leader among miners. Industry groups should engage in this process—either on their own or through relevant associations—to support voluntary initiatives such as this one that seek to improve governance of the diamond sector. Raising the bar on acceptable standards—many of which reputable industry members already do—defends the longer-term integrity of the industry. Doing so also isolates and highlights jurisdictions that pander to criminality and the lowest common denominator.

Alan Martin is director of research for Partnership Africa Canada (PAC), a non-profit organization that undertakes investigative research, advocacy, and policy dialogue on issues relating to conflict, natural resource governance, and human rights in Africa. He can be reached at amartin@pacweb.org[6].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/bigstock-Solution-5259818.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/bigstock-Beautiful-jewels-13828616.jpg

- All That Glitters is Not Gold: Dubai, Congo and the Illicit Trade of Conflict Minerals: http://www.pacweb.org/images/PUBLICATIONS/All%20That%20Glitters.pdf

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_1099.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_1193.jpg

- amartin@pacweb.org: mailto:amartin@pacweb.org

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/how-unethical-practices-in-the-global-diamond-industry-affect-you/