Instant information: Is transparency friend or foe?

by emily_smibert | August 17, 2017 8:47 am

[1]

[1]

By Isaac Mimar

There has been a tremendous amount of positive change in the way the diamond industry conducts business. The Kimberley Process (KP), implemented about two decades ago, is a means to control illicit or “blood” diamonds by introducing transparency to the diamond pipeline (including information on the country of origin, names of parties involved, and other chains of custody in the rough diamond trade). Official numbers indicate the Kimberley Process helped reduce illicit diamonds in the industry from 20 per cent of total diamonds to less than one per cent. The diamond trade does not want to be attached to crime, war, and other illegal activities, and the KP helps achieve that.

Confusion at the counter

Alas, transparency is less rosy on the retail and consumer side of the industry. With the advent of online diamond retailing in the mid-2000s, the industry rushed to put their diamond stock online. At the end of the decade, Rapaport online had several hundred thousand diamonds listed on RapNet, and Blue Nile had listed about 100,000 diamonds. Shortly thereafter, full Gemological Institute of America (GIA) certificates and live pictures were uploaded to the web, creating a confusing and excessive form of transparency. Consumers—who now thought they had enough knowledge and skill to make an informed decision about buying a diamond—were asking jewellers about crown angles, table sizes, pavilion depth percentages, etc. Ironically, many of these jewellers—not knowing the meaning of these terms—could not provide realistic answers to questions about a diamond’s scientific proportions. The trade was now becoming “hyper-transparent,” causing confusion for jewellers, and with it a loss in sales as many scrambled to learn the new terminology consumers had picked up online.

What’s the difference?

[2]

[2]Consumers did not realize a very good-cut diamond is already within the 90th percentile of what a perfect-cut diamond should be, while an excellent-cut would be near the 95th percentile of ideal proportions. If a very good-cut diamond has already reached 90 per cent perfection, why then care about table size, depth percentage, crown angle, and countless other metrics? The answer is a buyer should not care about these metrics, but rather about evaluating the SI2 rating of a diamond and how yellow the I colour is. Due to the excessive transparency found online, consumes were ignoring clarity differences between a good SI2 and a bad SI2 because the information on the GIA certificates did not distinguish a difference. Consumers started paying attention to factors with visible differences—like an ideal table size.

They were, incorrectly, too focused on the technical details of a very good-cut diamond versus an excellent-cut. They were learning an ideal table size should be 56 to 57 per cent, where 55 per cent or 58 per cent were less desirable or even unacceptable. This was an incorrect evaluation as consumers lack the industry knowledge to correctly translate these facts. This is the equivalent of presenting a patient with their MRI report and asking them to make a diagnosis and suggest a treatment. A good gemmologist or jeweller would tell the customer not to worry about a 57 per cent versus a 58 per cent table, as inclusions inside the stone which visibly affect the overall quality of the diamond are more relevant.

Seeking professional advice

[3]

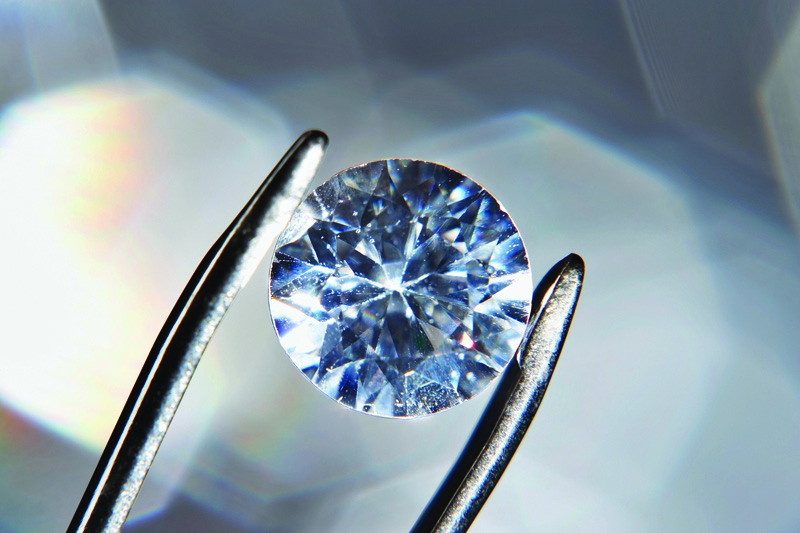

[3]Consumers are being provided irrelevant data, making sales at the store difficult. A customer looking online to buy an engagement ring is able to find hundreds of choices with a plethora of slightly different certificates all showing an equal amount of slight variances in measurements. However, they should be focusing on buying a nice quality diamond with inclusions positioned in inconspicuous places or on evaluating the overall brilliance and shine. This can only be achieved in the presence of a professional jeweller or gemmologist where they are able to compare physical diamonds for maximum value. Remember, value is not only about the lowest price, rather, the nicest stone for the lowest cost. An online shopper will choose the cheapest combination of clarity and cut leading them to purchase the lowest quality diamond, not the best value diamond.

If this online shopper was guided by a gemmologist, they would be shown the obvious deficiencies (which contribute to the low price) of the stone they selected. On a wholesale level, the cheapest diamond is not the best diamond as the market is efficient enough to price an inferior SI2 at a lower price than a nice SI2. In the online marketplace, this inferior SI2 is not differentiated because the assumption is all GIA-certified SI2s are the same. This speaks to how excessive transparency has led customers to shift their purchases from brick-and-mortar stores to the web, believing they are getting a better deal online.

[4]

[4]Dare to compare

Although transparency has been a net positive for the jewellery trade—addressing questionable diamond sourcing, chain of ownership, and the funding of wars—the hyper-transparency at the online retail level has reduced diamond sales at retail outlets. These sales have moved online due to consumers’ emphasis on (or distraction by) miniscule differences in diamonds. Online, consumers are left to make decisions based only on price, and are therefore not maximizing their purchasing dollars—purchasing a low-quality diamond at the lowest price. Hyper-transparency is misleading consumers by distracting them from relevant information to focus on the less relevant—offering a diamond on the basis of certificate evaluation rather than a physical, real-time comparison in the presence and under the guidance of a jewellery professional.

Isaac Mimar is CEO of MDL Diamond Merchants, a diamond house based in Toronto. A second-generation diamantaire, he has an economics and finance degree from the University of Toronto, holds a gemmology degree from Gemological Institute of America (GIA), and currently serves as treasurer of the Ontario chapter of the GIA alumni association. Mimar is also an active member of the Diamond Bourse of Canada (DBC) which is now affiliated with the World Federation of Diamond Bourses (WFDB). He can be contacted via e-mail at issac@mdldiamonds.com.

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/bigstock-Attractive-Young-Woman-With-Ea-120714071.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/bigstock-Portrait-of-tired-young-busine-92013986.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/bigstock-Diamond-held-by-tweezers-clos-148670369.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/bigstock-120012017.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/instant-information-is-transparency-friend-or-foe/