Is there a place for hue on diamond grading reports?

by charlene_voisin | May 1, 2014 9:00 am

By Hemdeep Patel

[1]

[1]

Over the last 90 years, some of the most prominent gemmologists and gemmological institutions have aimed to create scientific consistency. The principal goal of their endeavour has been to formalize a standardized, unbiased language to accurately describe diamonds and gemstones.

Unfortunately, some of these efforts run counter-intuitive to how the diamond trade works, causing quite a bit of criticism. One such area is the accurate description of a diamond’s colour grade. More specifically, I’m referring to the addition of hue (also known as tint) to diamond reports for stones in the E to Z colour range. This may seem quite redundant, since a number of wholesale lists exist indicating prices according to a diamond’s clarity and colour grade. However, no list provides any price distinction between hues of the same colour grade, which is exactly where subtle differences can impact a diamond’s appearance and eventually its price.

Grading, historically speaking

[2]The history of diamond colour grading can shed some light on how scales were developed and how they correspond to a stone’s price. In Europe, early colour grading terminology was based on well-known diamond-producing mines, with very little mention of hue.

[2]The history of diamond colour grading can shed some light on how scales were developed and how they correspond to a stone’s price. In Europe, early colour grading terminology was based on well-known diamond-producing mines, with very little mention of hue.

For instance, the whitest diamonds were identified as ‘Jager.’ This term derives from the Jagerfontein mine in South Africa, which was known to produce the whitest diamonds with very strong blue fluorescence. At the same time, an equivalent scale existed in North America. Here, a ‘Jager’ was classified as ‘finest blue white.’ Similarly, the term ‘river’ was used when referring to diamonds that were found in alluvial or river deposits; these were considered to be, on average, whiter than stones found in mines (Figure 1).

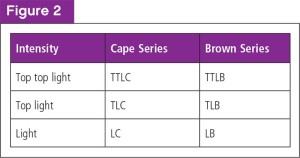

The term ‘Wesselton’ referred to the mine of the same name, while ‘crystal’ was used to describe the light yellow tint that was evident in the glassware of the time. And finally ‘Cape’ was a reference to the mine located in the coastal town of Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. This mine produced a wide range of yellow diamonds, including the famous canary. The range of Cape diamonds was further divided by the intensity of colour.

Through this part of the colour scale’s development, the primary focus of the terms was to avoid the use of the word ‘yellow,’ since a stone described this way meant it was sub-par. However, in the case of diamonds that would be graded light yellow and lower, the intensity of the colour would characterize the stone as fancy.

The European and North American scales are two of many used historically in the diamond industry. In all cases, they range from white to yellow, with no mention of brown. Until the early 1980s, the total number of brown diamonds mined was insignificant. For the most part, they were considered worthless, and in many cases, labelled industrial-quality, with little to no use in the retail sector.

New kid on the grading block

[3]Once the Argyle mine came into production in the mid-1980s, however, this all changed, with a significant influx of small brown diamonds entering the supply chain. The extraction cost of these stones was in the ballpark of $7 US per carat compared to $170 US per carat for rough that would later come out of Canada’s Ekati mine. This injection of cheap raw material and the growing low-cost labour force in India’s diamond cutting centres created an explosion of brown diamonds that could reach a much wider retail audience.

[3]Once the Argyle mine came into production in the mid-1980s, however, this all changed, with a significant influx of small brown diamonds entering the supply chain. The extraction cost of these stones was in the ballpark of $7 US per carat compared to $170 US per carat for rough that would later come out of Canada’s Ekati mine. This injection of cheap raw material and the growing low-cost labour force in India’s diamond cutting centres created an explosion of brown diamonds that could reach a much wider retail audience.

Initially, there was no clear cut direction as to how to colour grade these stones, given they did not fit any of the historical ‘white to yellow’ grading scales in use at the time. As brown diamonds became more and more prevalent in the marketplace, however, the trade developed a grading scale based on the one used for Cape coloured diamonds (Figure 2).

[4]

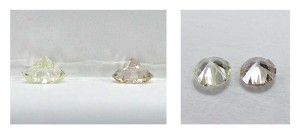

[4]Even though these two scales shared the same prefix in the terminology used to describe the stone’s colour (i.e. TTL, TL, and L before C or B), there was no real equivalency in the actual intensity. However, there is one key thing that holds true throughout the diamond trade: stones from the Cape series are more sought-after and more expensive than brown diamonds with similar intensity.

This difference in price is due to more than Cape diamonds simply having a longer history compared to browns; it all comes down to the stone’s overall look. One of the key factors justifying the difference in price boils down to blue fluorescence—those in the Cape series that fluoresce appear whiter, as opposed to brown stones with the same intensity of colour, which show no apparent change. As well, once set in jewellery, the TTLC to LC diamonds exhibit a warmer appearance than their counterparts in the brown colour range, which are almost grey. As such, experienced buyers look to purchase Cape series diamonds at the price of browns.

Should reports include hue?

[5]

[5]Through it all, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) developed a grading scale and terminology with the main goal of creating a standardized system for evaluating colour in a unbiased and accurate way. The colour grading scale starting at D to Z removes the biases of the previous scales by using terms that didn’t in any way imply or suggest the whiteness or lightness of a diamond’s hue.

Unfortunately, there is growing opinion that this colour scale is incomplete. As important as clarity and colour are to a stone’s cost, in some cases, hue can also be a factor when determining final price. While it’s my belief that indicating hue on a diamond report would be welcomed by many buyers, cutters and sellers would likely be in disagreement to do so.

Although an informal opinion, it comes with experience gathered in the early stages of our laboratory being established in India. I have found there was, and continues to be, a significant amount of resistance against additional information being included in reports (i.e. hue) that can further divide the diamond grading scale. In other words, diamond cutters and traders don’t want laboratories providing additional information that can possibly be used to shrink profit margins.

Without accounting for a diamond’s hue, a generalized colour scale allows each stone to be marketed as the sellers see fit. It would be up to the seller to emphasize the diamond’s yellow hue, and therefore, charge a premium. In the case of diamonds in the brown range, it is up to the seller to draw attention to the positive aspect of the diamond other than its hue.

As for gemmological laboratories, I am sure many would side with the seller, though not for the same reason. Instead, a gemmologist would suggest that to keep an unbiased opinion, only the diamond’s colour intensity needs to be observed and recorded. The addition of the stone’s hue is not a gemmological requirement, since the colour scale is only a measure of intensity. If labs were to include hue on reports, they would have to develop a new set of parameters to identify this property in brown and yellow diamonds.

[6]

[6]Though I am making an assumption, when I put on my scientific gemmological hat, I find this may be the only reasonable argument against adding hue to the colour grade. However, the obvious counter would be that universally, all gemmological reports are used to buy and sell stones. Further, it can be said a report’s details with a certain set of values has a corresponding price, which is based on the price lists that are readily available. It would also be reasonable to say that if reports have a certain value, and there was information that could possibly further impact a stone’s price, should it not be added so that a buyer is fully aware of a diamond’s characteristics to make an informed purchase decision?

Although I started putting this article together with a set of ideas of how I felt about this subject, while writing it, I can see how difficult it would be to pick one side and follow it through. The unfortunate thing is this issue cannot be resolved until a comprehensive, universally adopted scientific standard language is accepted amongst gemmological laboratories. Until then, we will do our best with what we have.

[7]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and GIA alumnus. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at contactus@hkdlab.ca[8] or sales@creativecadworks.ca[9].

[7]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and GIA alumnus. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at contactus@hkdlab.ca[8] or sales@creativecadworks.ca[9].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/bigstock-Beautiful-shining-crystal-dia-44706283.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Fig2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_0015.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_0021.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/IMG_0013.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Hemdeep-Patel.jpg

- contactus@hkdlab.ca: mailto:contactus@hkdlab.ca

- sales@creativecadworks.ca: mailto:sales@creativecadworks.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/is-there-a-place-for-hue-on-diamond-grading-reports/