Faceted nephrite jade and her 5Cs

By Samuel Michael Dilts and Andrew Sy Loo

“Before the 4Cs and Richard T. Liddicoat’s contributions (1953), a confusing alphabet soup was used to describe a diamond’s colour. In communicating colour quality to consumers, retailers used competing systems with descriptors like ‘A,’ ‘AA,’ and ‘AAA.’ There was virtually no agreement among firms as to what was considered an ‘A’ grade. Most diamond wholesalers used terms like ‘rarest white’ and ‘top Wesselton’ in addition to those mentioned above. In short, there were no standards that allowed for consistent evaluation and comparison.”1

~Gemological Institute of America (GIA)

This is where the nephrite jade industry is today—like a naked lunch of highly variable perspectives. Case in point: it has a semi-precious classification in Canada, but competes with gold as an investment in China.

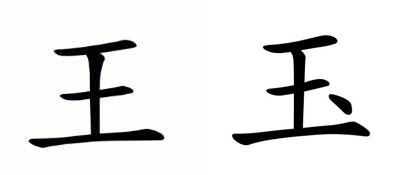

We must go forward with an attractive qualifier for nephrite jade. Let’s face it: nobody wants to say ‘nephrite.’ In China, this term translates to ‘soft,’ which is not exactly what we’re going for. Indeed, even nefrita, the Spanish translation, sounds more appealing than ‘nephrite.’

‘Jade,’ of course, sounds most attractive of all. Unfortunately, however, there is a tenacious semiotic root that twists and turns around on itself, profound and deep inside the psyche of a vast majority of jade, jadeite, nephrite, omphacite, and kosmochlor consumers: “‘Jade’ is jadeite and its from the East.”

Photos courtesy New Sun Design Group

Frankly, it behooves the entire industry to simply ‘have it out’ in one room—seriously.

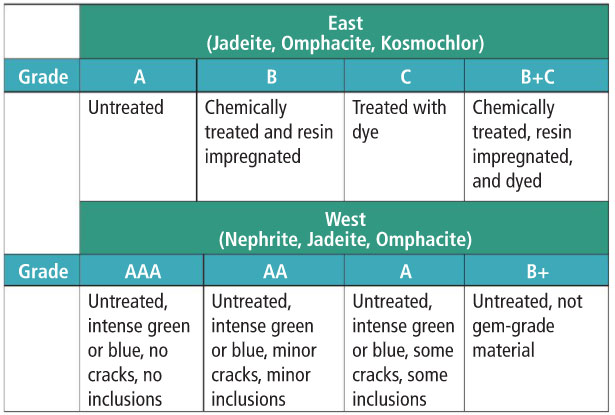

Before we come to blows, however, consider this: could there be anything more confusing than accounting for a degree of glue, chemical treatment, and dye in the sale of a gemstone in order to justify the socially ascribed value of its origin (as we see in the entirely independent Myanmar Imperial jadeite grading system)?

When we analyze gemstones, we search for characteristics desirable in the market: we assess colour consistency throughout our specimens, we like symmetrically cut facets demonstrating precision and skill, we ascribe value based on carat weight, and we generally want our gemstones clear of any impurities—no fractures included—regardless of the stone.

Indeed, we assess its natural colour, cut, carat weight, and clarity (obviously). Additionally, a good deal of thought goes into how different cultures will receive the product so markets can be defined in terms of the social value ascribed to a gemstone—similar to understanding Hoggle (of Labyrinth fame) and his relationship with his beloved plastic. Thus, this ‘fifth C’ (‘culture’) is sometimes referred to as the ‘Hoggle factor’—it’s cute and memorable, but doesn’t quite fit in with the other four.

A little 4C history

The diamond grading system is largely understood on a global scale by those both in and out of the jewellery and gemstone industry. One of the 4Cs (carat weight) is objectively measurable, while the other three have either a physiological or esthetic spectrum influencing how they are perceived or measured.

Until we are 3D-scanning faceted gemstones for optimal cut ratios, these three Cs are subjective, and they influence the value of a stone. Similarly, the value of a gem placed in one latitude has a different value when it is placed in another—or shall we say, a different ‘respect’ from one region to another. Do you know what the value of a two-carat, excellent cut, flawless, D-colour diamond is to a Cuban fisherman sitting in his boxers in the sun at the seaside with no other human in sight to his left or right for five kilometres? A two-carat diamond’s cultural value in this context is zero dollars (that is: C=0).

In the 1940s, GIA founder Robert M. Shipley presented the 4C system to his students to better communicate diamond grading in a concise and unanimous structure of defining characteristics.2 Each category of ‘C’ began to form its own respective variables as gemmologists and industry professionals used the system, and, through a process similar to the creolization of a pidgin dialect, the global diamond idioma and grading system evolved—even today, it continues to change as craftsmen, lapidists, and designers push the boundaries in cutting. (Plainly put: have you seen the horse head diamond?)

Photo by Veronica Cosio/courtesy New Sun Design Group

In 2006, 60 years after conceiving the 4Cs, GIA introduced a faceting and grading standard for ‘cut.’3 (The new diamond proportions required to describe the stunning ‘snowflake’ diamond by Ontario’s Wobito Gems, however, have yet to be defined.)

GIA itself noted, “An internationally accepted system for visually evaluating the appearance of fancy-cut diamonds does not exist at this time.”4

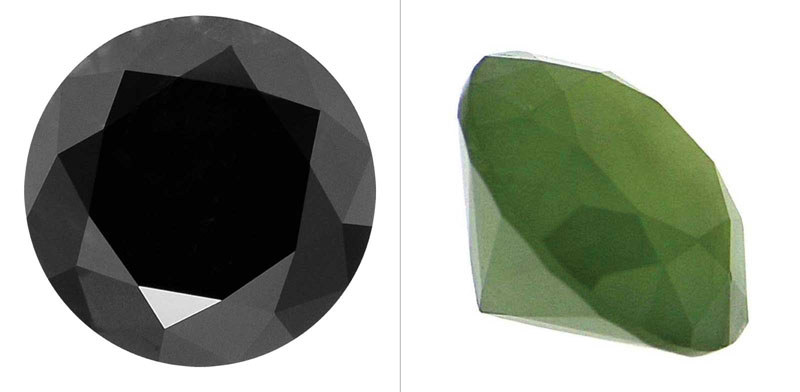

And what about the current state of black diamonds? If not for designer Fawaz Gruosi, until recently, you couldn’t give the things away (Figure 1). Indeed, not long ago this stone had a ‘5C value’ of zero.

We have only to look at the industry created by Gruosi and the grading system that evolved for natural black diamonds5 to envision how jade can fit into the world of faceted gemstones. Just as white diamonds on the shores of Cuba have a 5C value of zero, black diamonds on the shores of the Persian Gulf represent the other end of the spectrum (where white colourless diamonds usually sit). Subjectively.

Where does nephrite jade fit?

We can adapt faceted nephrite jade to the existing evaluation of coloured precious gemstones. In fact, all 4Cs for coloured gemstones work for nephrite jade; a certificate of origin (from a trusted appraiser) would account for the fifth C.

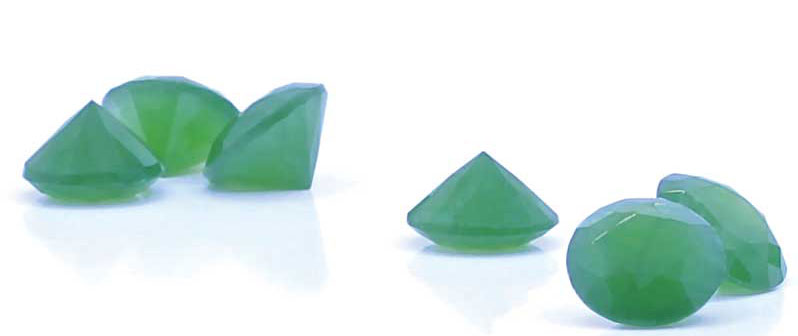

GIA and the Gemmological Association of Hong Kong (GAHK), together, recently established a testing and certification standard for jadeite jade, leaving the door open for nephrite as the jade outside the Eastern system.6 What the groups did not (and perhaps could not) address is how jadeite jade fits with other known precious gemstone grading systems, such as the 4Cs. It doesn’t mesh with these systems for one simple reason: jewellery professionals do not facet jadeite (not traditionally and not currently). Thus, the ‘cut’ in jade has never been applicable—though colour, clarity, and size certainly matter. Faceting high-quality nephrite jade like other precious gemstones (like black diamonds) reveals a mysterious new phenomenon for the gemstone world (Figure 2).

Since design, discovery, and marketing will continue to push the boundaries of the original 4C system, it makes sense nephrite is the jade of the West, with its cultural value firmly established independent of GIA and GAHK’s system for jadeite (see Table 1). Further, as nephrite jade was actually the original imperial jade of China, its value and participation in the modern gemstone world is obvious.

Reports

Too often, reports are misunderstood as certifications. A certification is established by reputation, such as a certification of origin for a raw material or designer. It is the last point of qualifying the stone to maximize transparency to your client. The certification is your word. It is also the Hoggle factor.

In contrast, a report is generated by mechanical equipment, laboratory analysis, and standardized interpretations. The report will guarantee your nephrite is nephrite, for example, but it will not explain nitty-gritty specifics, such as “as one’s eyes age, they can develop a yellow filtering effect on one’s vision… so, if your eyes perceive more yellow in a peach hue, it makes the colour appear less ‘peachy.’”7 Indeed, the tone you may want may not be the tone everyone else sees. That said, GIA’s coloured stone grading system is very concise and reports well for defining the colour characteristics of faceted gemstones with accuracy.8

Differing locales

When it comes to coloured gems, the variety these authors are most familiar with is jade.9,10,11 Nephrite jade is a Canadian mineral, still classified as semi-precious at its source. It has no official grading system at the level of the carat—which, after simply crossing the ocean, approximates the highly valuable nephrite jade that in China, for millennia, has been considered the purest object second only to the Emperor (Figure 3). In some circles, still to this day, the value of this mineral is incomparable.

Today, nephrite replicas of Dynastic pieces are often sold in European auction houses, posing as originals. Having lived in Hong Kong and taken particular interest in this trade (thanks, especially, to a welcoming Queen’s Road Central antiques dealer), this author saw firsthand the ‘underground’ trade of pieces between mainland China workshops and the antique shops of Hollywood Road and Queen’s. From these locations, the pieces may go to auction houses in France, Germany, or the United Kingdom, where they are ultimately purchased by wealthy Chinese collectors on the pretense of re-appropriating pieces stolen from China during British Imperialism. While the replica and artifact industry in China was once even larger than it is today, still, there are tens of thousands of skilled jade carvers across the border from Hong Kong, working year-round. They work with Canadian, Siberian, New Zealand, and Afghan nephrite, as well as Guatemalan and Myanmar jadeite.

High-graded offcuts from this industry are mechanically made by the thousands into beads to be sold in necklaces in central Hong Kong luxury jewellery stores, priced for as much HK$1 million (more than Cdn$162,500). Delicious nephrites from northern British Columbia are sold as Xinjiang jade beads, bangles, talismans, pendants, and gemstones. Only now is faceted nephrite entering the market after millennia of nephrite jade use. With jadeite on its own in the East, the West can own nephrite as its jade and eliminate all the confusing talk. In fact, with the exception of the great Mayan jadeite industry, which still persists today, nephrite is identified as the jade, typical of all the best known jade deposits in North America—including Wyoming, Big Sur, Washington, British Columbia, and the Yukon, as well as some lesser-known deposits in Ontario, Newfoundland, and Baja California.

A matter of colour

Photo courtesy Fawaz Gruosi

The Western grading system does not include a scaled value for manipulated or worked stone (i.e. imperial jadeite impregnated with glues or dyes is still classified as imperial jadeite). Nephrite impregnated with glues or dyes is not a Western practice and is generally frowned upon by stone workers. In western countries, the eastern grading system is typically not discussed. This system grades degrees of treatment because values vary according to market colour preferences, but the value of our fifth C is so high that origin trumps colour.

The published 2016 Standard Methods for Testing Fei Cui (Jadeite) in Hong Kong is 52 pages long, making it the most detailed approach to coloured gemstone testing and grading in the world.13 It is specific for jadeite, preferably from Myanmar; however, colours of jadeite from Guatemala, which approximate the imperial green jadeite from Myanmar, are sold in the Chinese market as ‘imperial jade.” To be clear: ‘imperial green’ is a desirable colour, while ‘imperial jade’ is the jadeite from Myanmar. This practice is common; even diamond dealers quote the ‘origin’ of their diamonds as Antwerp, Belgium—even though there are no diamond mines in Antwerp.

“There are several gradation systems to help jewellers communicate colours; however, it is essential those involved use the same system—and this doesn’t often happen!” writes Bénédicte Lavoie in Jewellery Business (Feb. 2021).14 Lavoie references three independent colour grading systems used in the industry. As noted above, however, physiological degradation of the human eye can develop a yellow filtering as one ages. Therefore, the consumer, in the end, is going to tell the seller what colour they see.

Where do we go from here?

To apply the 4Cs to nephrite jade (Western jade), we had to do three things:

- Identify a 5C requirement

- Cut the best jade into facets

- Name it in a way where we can talk about it

The categories for jade, as in the case of diamonds, will begin to define their own variables.

As a fifth C (cultural value), the grade prescribes indicators of social value. This, in turn, may influence market prices, marketing, provenance, directed design agendas, industry trends, labour conditions and rights at the stone’s source, import and export infrastructure, mining development, policy, and mining practices. This is, in fact, what we already see: this valuation is very real and can greatly influence a gemstone’s identity and worth in the market. It comes to the customer as the certification, or the seller’s word (or the media).

The jade products in the market suitably adapted to an application of the 4Cs could only be faceted stones (so far), as the variable ‘cut’ refers to faceting. Although cabochon cut works, too, the standard will need to be defined.

True, north, strong, and green

Jadeite jade has made its point: it wants a world entirely to its own. So, we get nephrite as our Western Jade—nothing wrong with that. Let’s keep it! After all, it was once considered the ‘Imperial choice’ and, last we checked, Canada was part of an Empire. Maybe we are home to Imperial jade now? We don’t have to go anywhere to get it, nor treat it with anything to give it value. It’s not semi-precious; it’s the best there is: true, north, strong, and evergreen jade, sourced directly from Canada. As a precious gemstone, we can enter the Western jewellery market with a steadfast luxury product, admired for millennia, with a new outlook for jewellery fashion.

Samuel Michael Dilts, B.Sc., a graduate of the Australian National University, is an industrial designer and a sculptor. He is the founder of the New Sun Design Group of Vancouver and BC Jade Ltd. of Hong Kong. Dilts is the creator of several patented and trademarked jade products designed to advance the sustainability of the jade value chain (JVC) for North American industry professionals and to build a brand for Western jade. He can be reached via his website, NewSunDesignGroup.com.

Samuel Michael Dilts, B.Sc., a graduate of the Australian National University, is an industrial designer and a sculptor. He is the founder of the New Sun Design Group of Vancouver and BC Jade Ltd. of Hong Kong. Dilts is the creator of several patented and trademarked jade products designed to advance the sustainability of the jade value chain (JVC) for North American industry professionals and to build a brand for Western jade. He can be reached via his website, NewSunDesignGroup.com.

Andrew Sy Loo holds a B.A. from Windsor University as well as a post-graduate degree in geology from Peking University. He is a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (Gem-A) and has been a gemstone educator for nearly two decades, having joined the gemstone laboratories in Hong Kong and Antwerp. Loo currently works as a gemmologist, with a private client base of collectors, jewellery retailers, auction houses, and gemmological associations. He can be reached via email at andrewsyloo@gmail.com.

Andrew Sy Loo holds a B.A. from Windsor University as well as a post-graduate degree in geology from Peking University. He is a Fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (Gem-A) and has been a gemstone educator for nearly two decades, having joined the gemstone laboratories in Hong Kong and Antwerp. Loo currently works as a gemmologist, with a private client base of collectors, jewellery retailers, auction houses, and gemmological associations. He can be reached via email at andrewsyloo@gmail.com.

References

1-4 See “The History of the 4Cs of Diamond Quality,” published by GIA. Find it online here: https://4cs.gia.edu/en-us/blog/history-4cs-diamond-quality/

5 For more, see “Black diamond grading.” Find it online here: https://www.withclarity.com/education/gemstone-education/black-diamond/grading

6 Standard Methods for Testing Fei Cui in Hong Kong. Liu, E., et al. The Gemmological Association of Hong Kong, 2016.

7 See “Interpretation of colour” by Bénédicte Lavoie, published February 2020 in Jewellery Business. Find it here: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/interpretation-of-colour/

8 See “GIA colored stone grading system,” published by Yves Lemay Jewelry. Find it here: https://yveslemayjewelry.com/blogs/jewelry-guides/gia-color-grading-system

9 See “This business of jade” by Samuel Michael Dilts, Laura Acosta Vidales, and Andrew Loo, published July 2019 in Jewellery Business. Find it here: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/publications/de/201907/?page=30

10 See “Making the grade: Crucial factors in assessing jade’s value” by Samuel Michael Dilts, Laura Acosta Vidales, and Andrew Loo, published December 2018 in Jewellery Business. Find it here: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/publications/de/201812/?page=46

11 See “Code green: B.C. jade producers work toward a code of conduct” by Samuel Michael Dilts, published June 2016 in Jewellery Business. Find it online here: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/publications/de/201607/?page=64

12-13 See note 6.

14 See note 7.