Cutting edge: How laboratory-grown diamonds are innovating diamond design

By Alethea Inns

Photos courtesy GSI

Gemmological laboratories are the proverbial canary in the coal mine of materials being certified for the retail jewellery market. Indeed, the scientists working in these facilities are highly trained in the gemmological analysis of diamonds, the detection of laboratory-grown and coloured stones, and the appraisal of finished jewellery. Those working in these labs examine millions of pieces of jewellery and individual gemstones each year and, as such, are among the first to note new and exciting diamond trends.

One such observation (born from the explosion of jewellery industry technology) are laboratory-grown diamond growth processes and the evolution of diamond cutting tech. Specifically, laboratories have increasingly seen spectacular fancy-cut laboratory-grown diamonds which are often beyond the standard cuts and colours possible with natural diamonds. These stones are fun and fantastical for diamond-lovers.

Let there be light

The earliest diamond cutters discovered that the addition of even a few rudimentary facets on a diamond crystal could unlock its potential for incredible beauty. Diamond interacts with light once these facets let the light in.

So begins the history of diamond cut! With natural diamonds, cutters must negotiate the rough’s shape, size, colour zoning, and inclusions to find the most profitable balance between the diamond’s carat weight and the impact of the cut. The ultimate cutter’s choice is always carat weight versus beauty. Diamonds with better cut grades typically require greater weight loss from the rough (Figure 1).

There are two main objectives:

- Natural diamond rough is valuable, so minimize weight loss of the rough to maximize the final polished diamond weight.

- Cut a diamond with a make good enough to have decent brightness, scintillation, and fire.

Good cut is so important to the diamond industry that a mathematician by the name of Marcel Tolkowsky based his doctoral thesis around the conundrum. In 1919, Tolkowsky, who was a member of a family of Polish diamond cutters, developed a set of proportions of the round brilliant-cut diamond to provide the best optical performance. He asserted that, if a diamond is cut too deep to retain weight in the girdle or pavilion, light will escape, creating a dark, dull stone. The same can be said if a diamond is cut too shallow to maximize face-up size.

Tolkowsky’s analysis is widely accepted by diamond experts and, even today, remains the basis for ideal cut with only very minor modifications.

Diamond Cut 101

Undoubtedly, cut is the most important of the 4Cs, as it quantifiably determines a diamond’s beauty. When we talk about diamond cut, it can refer to a few things: finish, design, or light performance.

Finish describes the craftsmanship—the polish and geometric symmetry of the diamond. It is how well the facets are polished, as well as their uniformity in size, shape, and placement.

Design, meanwhile, is the outline of the diamond, along with the actual shape of the facets, their spacing and placement, and their size. To some degree, design also includes optical symmetry—the internal interaction of all the facets of a diamond.

Finally, light performance is how efficiently the diamond returns light to the observer’s eye. This consists of the aforementioned finish factors, but also goes deeper into looking at the factors impacting the diamond’s light performance (i.e. brightness, contrast, leakage, and dispersion), as well as the impact of the relationship between the angles and relative percentages of the diamond’s proportions. The latter includes girdle thickness and durability, weight ratio (or “spread”), and changes in light return as the diamond is tilted through a range of viewing angles.

When compared to a poorly cut diamond, the quality of a well-cut one is obvious: it is brighter, has uniform patterning, and is visually more pleasing to the eye. Additionally, well-cut diamonds can look larger face-up, and even sometimes have a better apparent colour because they are brighter, along with enhanced clarity if the cut obscures inclusions.

Cutting laboratory-grown diamonds

While laboratory-grown and natural diamonds are both diamonds (i.e. carbon crystallized in the cubic crystal system) and are essentially identical in optical, physical, and chemical properties, they can be quite different in terms of their growth, structures, and internal/external irregularities. Indeed, cutters report laboratory-grown diamonds feel quite different on the cutting wheel as compared to their natural counterparts.

There are currently two mainstream methods of growth processes for laboratory-grown diamonds: high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) and chemical vapour deposition (CVD). Each yields its own type of rough from its respective processes.

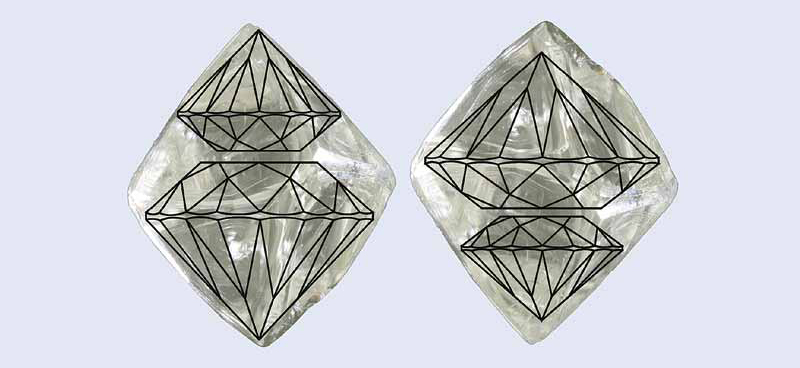

The difference in crystal shapes between HPHT and CVD diamonds is primarily a result of the growth conditions and the natural crystallographic structure of diamond. HPHT diamonds, which are grown at higher pressures and temperatures, develop cuboctahedral shapes, and CVD diamonds, grown at lower pressures and temperatures, have a more regular cubic shape (Figure 2).

While both CVD and HPHT diamonds have a cubic crystal structure, the quality and homogeneity of the crystal can vary between the two types. CVD diamonds grow layer by layer, and their crystal structure might have some variations and impurities, resulting in slightly different mechanical properties. Meanwhile, HPHT diamonds are grown as a single crystal from a seed, which can lead to more consistent and homogeneous material.

Photos courtesy Star Blue Diamonds

Rough CVD diamonds are surrounded by a polycrystalline material of graphite and non-diamond carbon, which must be removed prior to planning the cut of the rough, as it impacts estimations of surface size, clarity, and colour. This removal requires laser ablative techniques, as the layer cannot be taken off with a diamond cutting wheel. The cutter then needs to find the grain of the diamond on the wheel. This can cause greater weight loss from the rough, but, with laboratory-grown diamonds, it is less of a risk. As CVD diamond rough tends to be quite shallow, shallow-style cuts are typically used in the finished product.

The future of diamond cut

Experimenting with diamond design can be pricy—natural rough is expensive, as well as sometimes unpredictable on the cutting wheel, given its growth is controlled by nature and not regulated in a laboratory. Laboratory-grown diamonds allow designers to experiment with different cuts without so much risk and uncertainty.

The same tools and processes are used for working with both natural and laboratory-grown diamonds; however, because laboratory-grown rough is more uniform in shape and crystallinity, cutters can more easily adjust factors (such as brilliance, fire, or scintillation), and choose to maximize one over the other without the physical and financial limitations of natural rough.

Beyond standard diamond cutting tools, though, we are now seeing developments in diamond cutting and polishing that have made it possible to cut and shape diamonds in ways previously thought to be impossible or cost prohibitive.

We have entered an age of cutting-edge laser sawing and laser marking technologies. We also have the added advantage of 3D scanning. Combined, these technologies make virtually any shape possible. The days of standard rounds, princess, hearts, pears, ovals, and cushions are now being met with innovative outlines, including bunnies, stars, butterflies, letters of the alphabet, Christmas trees, and more (Figure 3). Diamond cutters can include more complex patterns and motifs as part of the diamond design by using laboratory-grown diamonds and can even customize things like the sparkle size and speed, contrast patterning, and other visual elements by experimenting with how facets are planned and placed on the diamond.

The nature of the CVD rough creation process—in which diamonds are grown on flat, wafer seed crystals—lends itself to bolder and more experimental designs, explains Debbie Azar, president of Gemological Science International (GSI).

“We’re seeing CVD diamonds in increasingly artistic shapes because laser cutting has advanced what diamond cutters can do, and laboratory-grown material is less risky to experiment with because of the cost factor,” she says.

Laboratory-grown diamond growers are also experimenting with size and growing diamonds that are bigger and bigger. It seems like every month there’s news report of yet-another “world’s largest laboratory-grown diamond” breakthrough.

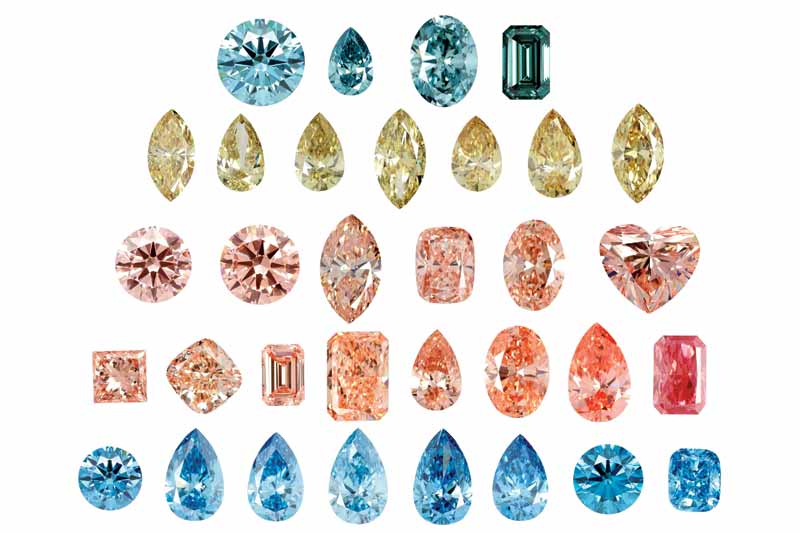

Control over colour has also increased. In the past, post-growth treatments were somewhat unpredictable as to the outcome of the final hue of the diamond. Today, though, these can be more carefully controlled (Figure 4).

“When it comes to colour, there are no limits,” Azar says. “Diamond growers are tapped into the science of diamond colour and can create whatever colour they’d like based on the impurities they add, as well as any post-growth treatments such as irradiation, HPHT processing, and annealing. We have even seen laboratory-grown diamonds that have been intentionally colour-zoned to give an ‘ombre-like’ effect!”

Gemmological labs have certainly seen the impact of advanced cutting and diamond growing technology on the diamonds submitted for grading reports, with innovative cutting designs, custom colours, and, of course, cutters being able to experiment with the balance between brightness, contrast, scintillation, and colour zoning. Love them or hate them, laboratory-grown diamonds are certainly bringing innovation to the art and science of diamond cut—it’ll be interesting to see where the industry goes from here!

Alethea Inns, BSc., MSc., GG, is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA). Her career has focused on laboratory gemmology, the development of educational and credentialing programs for the jewellery industry, and the strategic implementation of e-learning and learning technology. Inns is chief learning officer for Gemological Science International (GSI). In this role, she leads efforts in developing partner educational programs and training, industry compliance and standards, and furthering the group’s mission for the highest levels of research, gemmology, and education. For more information, visit gemscience.net.

Alethea Inns, BSc., MSc., GG, is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA). Her career has focused on laboratory gemmology, the development of educational and credentialing programs for the jewellery industry, and the strategic implementation of e-learning and learning technology. Inns is chief learning officer for Gemological Science International (GSI). In this role, she leads efforts in developing partner educational programs and training, industry compliance and standards, and furthering the group’s mission for the highest levels of research, gemmology, and education. For more information, visit gemscience.net.