By Lauriane Lognay

Photo by Lauriane Lognay, Rippana Inc.

Anyone and everyone who has worked in the jewellery industry has encountered gemstones sourced from Afghanistan. The name ‘Afghanistan’ means ‘Land of the Afghans,’ in reference to the country’s largest ethnic group at the time of its formation (in present day, this group is known as the Pashtuns).

Afghanistan has long been a land of conquering and being conquered. Indeed, historically, it is a country full of strife and conflict, both internally and externally. Located between Asia and Europe, Afghanistan has often found itself in the middle of international disputes. Darius I of Babylonia, Alexander the Great of Macedonia, Genghis Khan, and Mahmud of Ghazni are just a few of the several conquerors who rained down on the country to make it their own.

It was not until 1921 when, following three British-Afghan Wars, Afghanistan was declared an independent country. In 1926, a monarchy was established (in place of an emirate), leading to certain stability for the next 40 years or so. This period was followed by a series of coups, an overthrowing of the monarchy and then of the government, assassinations, and a heavy dose of Soviet influence.

The history of this storied country is certainly long and complicated, and a simple article would not be enough to explain its years-long intricate complexities. The true purpose of this condensed history serves, instead, to demonstrate how Afghanistan has been in a state of instability for centuries. Further still, the overall objective of this column is not to take sides in this conflict, but, rather, to focus on the impact of this instability on the gemstone industry and how our actions might unwillingly influence it. While we do have a limited use of words here, I will try and express the limitless entity which is Afghanistan soil.

Land of the gems

Afghanistan has long been an area of endless possibilities for the gemstone industry. Known for its amazing blue mountain of rich lapis lazuli, the country, too, overflows with colourful tourmalines, turquoises, peridots, emeralds, aquamarines, rubies, sapphires, and much more.

Deposits and mines are often hidden in the mountains, making access difficult for anyone other than the miners, who are living there in hopes of finding facet grade rough quality gems. The Afghan culture is as rich as the country’s soil, and quite different from that of North America. While the history itself is not the most peaceful one, however, Afghan gem dealers and miners are as kind and eager to share their culture as anyone else who shares the same passion for gemstones.

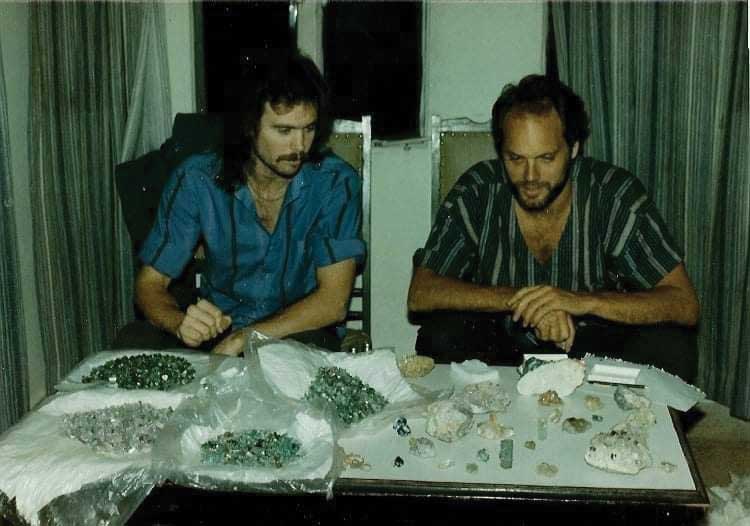

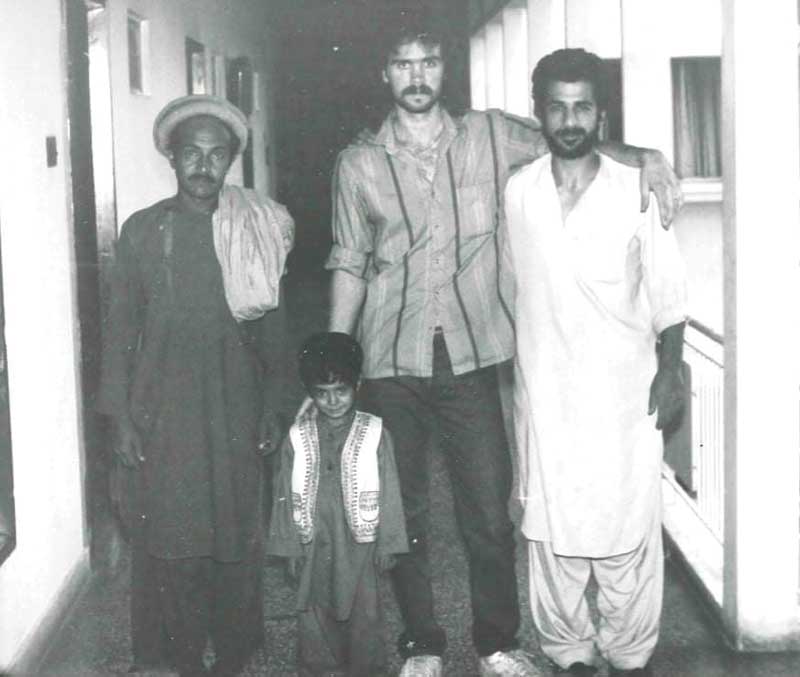

Photos by Sid Tucker

While researching this column, I spoke to industry friends and acquaintances—gemstone dealers, writers, and jewellers alike. Amidst the Taliban’s recent return to power in Afghanistan, these jewellery professionals expressed several questions and concerns:

• What to do with the current situation?

• What is our responsibility?

• Should we boycott and never buy an Afghan gem again?

• Moving forward, are prices going to skyrocket for every piece of treasure unearthed there?

Amidst the uncertainty, however, consider these facts:

Extraordinary specimens of gemstones adorning the market today come from Afghanistan. From the discovery of massive top-quality lapis boulders, to giant clusters of untreated aquamarines, to flawless emerald crystals, the country is easily one of the richest in terms of minerals and gemstones. Regarding specific mining sites, the Panjshir Valley in the Hindu Kush Mountains is, amongst other sources, a place where you can find emeralds and aquamarines, while the Jegdalek region is known for its rubies. For more than 6000 years, lapis lazuli has also been mined in the Badakhshan province of northern Afghanistan.

Most of Afghanistan’s mines are family- or tribal-owned (with a just a few company- and/or government-owned exceptions). For miners, the land is theirs and has been for generations. Because the mines in the mountains are treacherous and hard to reach, most do the digging themselves with little to no heavy machinery. Further, to dig deeper into the harsh mountains (for emeralds, tourmalines, etc.), these miners fabricate and use their own powders to create dynamite. (The government is trying to implement laws with permits to help categorize all the exploitation sites via GPS and satellites, but the mission is long and unfinished.)

To better understand our responsibility as jewellers and gemmologists within the context of present-day Afghanistan, I spoke to Idaho-based gem professional and international traveller, Sid Tucker.

Lauriane Lognay (LL): Would you introduce yourself and explain the ties you have with Afghanistan?

Sid Tucker (ST): I survived a catastrophic diving accident when I was 19. Through the clarity that followed, I know life is far too precious to waste on endeavours that do not fascinate me.

I have always been drawn to rocks, minerals, gems, and made a committed decision to them as a vocation. While this was a few years before I was mobile enough to fully engage in the undertaking, I meet a man a generation older who had been part of a large ‘hippie migration’ to Asia in his youth, and, over the course of time, had learned to finance his travels via importing exotic goods. He was very active in the purchase of tribal rugs in the market in Peshawar. He didn’t really understand the gem business, but brushed shoulders with it while there and recognized the potential for import to the West. I paid him for locations, contacts, and the provision of political protection my first trip. I had access to these resources once I arrived, but, beyond that, was basically on my own. The political protection was important, as Peshawar was effectively a war zone at the time.

LL: Why did you go to Afghanistan? What was the gemstone market there like?

ST: I made multiple trips during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the mid to late 1980s. There were more Afghanis than Pakistanis in Northern Pakistan at that time, and gem business was primarily transacted in Peshawar and the surrounding area. Ahmad Shah Massoud was the leader of the Northern Alliance, fighting the Soviets out of the mountains of Panjshir with financial and military support from the United States. He was regarded as a living legend by the Afghan people and revered on an almost-sacred level. He was eventually assassinated by Al-Qaeda the day before the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

There were many refugee camps north of Peshawar. The Pakistani government treated [this area] as islands of Afghan sovereignty, and one had to pass a customs’ check to enter leave, even if they were [travelling] only a few hundred metres.

Afghan fighters would leave their families in the refugee camps on the Pakistani side for safety and travel back and forth to fight the invaders. Gems were a form of concentrated, easily transported value. If a deal was made, they would use the money I spent with them to feed and provide for their family, re-arm themselves, and cross back into Afghanistan.

Photo by Lauriane Lognay, Rippana Inc.

Negotiations on gems were always very ‘spirited’ by western standards—to the point where, had a Westerner observed the meeting, they may have misunderstood it as an altercation. A minimum of Farsi, Pashto, English, and Urdu languages were almost always in play. Regardless of how heated the proceedings, however, they paused abruptly at prayer times [and talks were] resumed only after the responsibility was fulfilled.

At the end of any given negotiation, regardless of sale or impasse, all parties remained friendly. I was treated with such graciousness by the Afghan people, I was forced to develop a strategy of moving somewhat secretly to get business done, as any who recognized me in passing generally insisted I join them for tea or a delicious home-cooked meal.

LL: What do you think the best course of action would be for the people who buy gems from Afghanistan?

ST: Regarding the current crisis in Afghanistan and how it correlates to our gem business, the Taliban are not miners. Mining in these regions is, for the most part, done on an individual or family scale. The Taliban is going to take a slice of any pie it is aware of; however, since most gem business is conducted hand-to-hand, it is unlikely to be traced. Any ‘gem boycott,’ regardless of how well intentioned, will have little or no impact on the Taliban, but could certainly make life more difficult for miners trying to provide for their families.

Drive forward

By and large, the conclusion on this issue can be reached via this wonderful insight from Sid Tucker. Buying Afghanistan gemstones continues to help families and tribal-owned mines. Boycotting them will not impact any Taliban business; the mining industry in Afghanistan, while still largely uncontrolled, remains local and unchanged. Though the difficulties with importation may soon impact prices, this is nothing we have not foretold of the gem industries ever-growing market.

I am certainly not alone, however, in thinking this is not the last time we will be faced with an ethical dilemma regarding Afghanistan and its gemstones. Until then, the preferred course of action for us, as jewellery professionals, will be to continue admiring and buying gems of this origin and supporting the nation’s family-owned mines.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA), and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana Inc., a Montréal-based company working internationally in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached via email at rippanainfo@gmail.com.

Lauriane Lognay is a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain (FGA), and has won several awards. She is a gemstone dealer working with jewellers to help them decide on the best stones for their designs. Lognay is the owner of Rippana Inc., a Montréal-based company working internationally in coloured gemstone, lapidary, and jewellery services. She can be reached via email at rippanainfo@gmail.com.