Mastering the method of manufacture

by jacquie_dealmeida | February 1, 2016 9:00 am

Knowing how a piece was made can help in the appraisal process

By Carole C. Richbourg

[1]

[1]When preparing an appraisal for insurance coverage, detail is crucial. Gone (hopefully) is the use of a one-sentence description attached to a value. These days, the courts are increasingly seeking out professional qualified appraisers who offer more than an off-the-cuff opinion. Thorough knowledge of the subject property and its relevant market are de rigueur; detail ensures the client receives the appropriate replacement in case of loss or damage.

One component of this detail some might find challenging—and sometimes gets lost amid the descriptions of the centre diamond, metal, type of finish, setting, etc.—is determining the method of manufacture. When the item is new, this detail can help rank the piece to determine the relevant market. When the piece is not new, how it was put together can offer valuable clues to the era in which it might have been made.

This discussion focuses on four of the most common manufacture methods—past and present—used in jewellery: casting, die-striking, stamping, and hand construction. While entire articles can be written about each of these subjects, the point is to become familiar with evidence of a particular technique. Photographs and tips aid both the novice and seasoned appraiser to ask themselves the right questions to determine which method(s) were used.

Follow the clues

[2]

[2]a CAD/CAM wax mould.

One of my dearest friends is a retired master goldsmith/platinumsmith. He trained in England in the late 1950s and learned traditional techniques of making jewellery. He is also quite the history buff; this article benefits from several hours of conversation between us. Whenever I am stumped by a piece, I call him. His thorough understanding and unique way of looking at jewellery never fail to ultimately make me comfortable with my decision on the way a piece was put together. He worked for many years at one of the stores where I was employed as a salesperson. When I could sneak off the sales floor, I would pepper him with questions: Why was this cast? How old do you think this is? What is the difference between stamping and die-striking? What are the methods of choice for a goldsmith? And on and on. He was all too happy to answer my questions and was ever-patient in showing me what he was doing and why. When my shift was over, he’d let me sit at the bench and give me things to do like sawing Abraham Lincoln out of a penny. Then he’d tell me to examine the marks the saw made and remember what that looked like.

Years later, I took a jewellery fabrication course at the Revere Academy of Jewelry Arts in San Francisco.

I learned to file, forge, form, anneal, and solder. (I found out soldering is not my forté, as I’m not really all that comfortable around a highly combustible pressurized tank of gas and oxygen!) Even though it is certain

I will never make a living as a goldsmith, the course was invaluable for helping me recognize the telltale signs of the various methods used to make jewellery.

Where to start? First, turn the piece over! The back of a brooch, the underside of a ring or bracelet, the inside of a locket. This is where your search for clues begins.

A case for casting

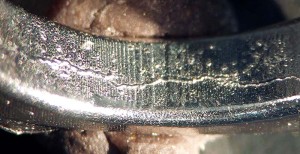

[3]

[3]Note the telltale signs of cracking and pitting.

Casting is one of the oldest known methods for making jewellery and has been around for thousands of years in various forms. Very simply, it involves a process that creates one or multiple items without having to make each one from scratch. The most prevalent method—lost-wax casting—involves making a model from an organic material like wax or resin, either carved by hand or machine, and more recently, grown with a 3-D printer. The model is packed into investment and dissolved by heat to form a negative void. Molten metal is then injected under some form of centrifugal or vacuum force, pulling it into the cavity. Ages past, goldsmiths used to sling the mould around by hand, kind of like David whirling his slingshot at Goliath (but of course, not letting go).

Lots of things can go wrong with casting, but the good news is, mistakes leave traces. On occasion, the only clue one might have that an item was most likely cast is the piece itself. It would have been almost impossible to create a true 3-D piece of jewellery any other way.

All qualities of jewellery can be cast, so you might see the ridiculous (e.g. an inexpensive diamond tennis bracelet with imperfect diamonds cast in place) to the sublime (e.g. a Cartier brooch). In most cases, antique platinum pieces, especially filigree, are not cast. Generally speaking, cast pieces appear heavier and bulky. Upon closer inspection, though, you might find the piece is a reproduction. At the turn of the century, Edmond Fouch of France developed the first oxy-acetylene torch, which produced a very hot flame, far hotter than any gas flame before it. With this new tool, and given platinum’s ductile strength, craftsmen were able to create delicate pierced pieces, which were almost always hand-fabricated. It’s not until recent times that we see any quantity of cast platinum pieces; most of what you will see is bridal jewellery.

What to look for in a cast piece:

- Porosity ranges from microscopic to large pinholes and can be caused by trapped gasses or when the metal is not heated or cooled properly. Metal that cools too quickly can also result in cracking. Porosity can go deep into a casting and sometimes is not revealed until the final polishing process.

- Lack of joint/solder marks, which can be a sign of a one-piece casting.

- Seam marks on the inside of castings made from rubber moulds.

- Even when a piece appears to be made of two colours of metal, the item can still be a one-piece casting; the top prong work holding any diamonds might have been rhodium-plated to make the piece appear more labour-intensive.

- The 3-D nature of the piece would not lend itself to the use of other techniques, such as die-striking or hand-fabrication.

- A slightly matte ‘skin’ on the underside and inside holes or crevices of a design.1 In addition, the matte skin can have the appearance of moiré silk, a sure sign the wax mould was made using CAD/CAM, which implies it’s not ‘antique.’

Jewellery can be one-piece cast or assembled of various cast, hand-made, and pre-fabricated components.

What to look for in an assembled piece:

- Visible solder joins between components.

- Porosity in the solder joining the components.

- Identical mould lines from the original wax design. This is pretty good evidence a piece has been cast and assembled, especially when it’s a bracelet. One would see an identical line or imperfection repeated inside each cast link.

- Noticeable differences in polish between the two metals

(e.g. platinum top with a yellow gold base).

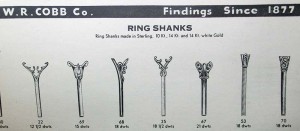

Putting the pressure on die-striking

[4]

[4]from a W.R. Cobb catalogue,

circa 1900.

Die-striking is a process using immense pressure to form precious metal into a dense, durable shape. Die-struck rings are produced by taking a blank (i.e. a flat piece of formed metal) and striking it into an engraved metal die. One of the most common examples of die-striking is a well-made signet ring, which has a much more compressed molecular structure due to how it was formed. As such, it can be engraved, with superior results. The difference between hand-engraving a complex monogram in a cast signet and its die-struck counterpart can be likened to engraving on a bar of pumice stone. In a die-struck piece, you won’t see any porosity or cracks, and it will have a higher heft, too.

Good-quality findings are very often die-struck. Engagement rings and wedding and anniversary bands of good quality are also often die-struck and assembled.

If you see trademarks from Jabel, Cobb, or Van Craeynest, you’ll know these pieces were made from dies, some of which are more than 100 years old.

What to look for in a die-struck piece:

- A mirror finish inside and underneath.

- Sharp, crisp edges and a well-defined design.

- Heft.

Findings, earring backs, pin assemblies, and clasps are often die-struck.

Breathe a stamp of relief

[5]

[5]An older form of die-striking, stamping is the process of pressing metal into a mould, resulting in a piece that shows relief or an embossed pattern. Older rolled gold or gold ‘clad’ jewellery of the Victorian period was often stamped and produced for the masses. Cufflinks, large Victorian brooches, earrings, and bead necklaces were stamped out and soldered together.

What to look for in stamped jewellery:

- Wear on corners or near catches where one would normally see it. For instance, the top layer of gold might have worn through to the centre piece, revealing the base metal layer.

- Age—pieces formed using this method usually look heavy, although lightweight Victorian jewellery was often stamped out and assembled.

- A decorative pattern on the metal—it is not deep enough to have been engraved by hand and the piece is flat on the underside. Sometimes the pattern is accented with enamel.

- The jewellery is three-dimensional, with a top and sides.

In general, making stamped jewellery comprises one or two steps and then the findings are attached.

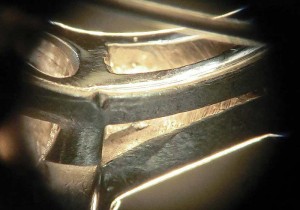

Hand construction—a very broad subject

[6]

[6]of a hand-fabricated piece.

Methods of hand construction include any of the previously discussed, but generally speaking, the term ‘hand-fabricated’ means the piece was made completely by hand. Take, for instance, a novelty brooch—the figural portion is cast, the original mould is hand-carved, and the pin stem is made of hand-drawn wire, hardened so as not to bend. And finally, the rotating safety clip is also handmade and assembled. Processes used include: drawing wire, sawing, piercing, soldering, filing, forging, drilling, etc. Tool marks are our salvation. And remember, just because a piece was handmade doesn’t mean it was well done.

What to look for in a hand-fabricated piece:

- Tool marks made by a saw, file, and/or hammer. The best way to recognize these marks is to examine pieces you know have been hand-fabricated. A good example is repoussé, which is a decorative technique whereby 3-D designs in high or low relief are formed from the backside with specialized tools. It doesn’t hurt to take a goldsmithing class or two to become familiar with the principles of construction. There are also resources online that explain in detail the processes and are well worth a look.

- Flashing in the drill holes might be seen in less expensive or sloppily made jewellery.

- Finishes—examples include Florentine, planished, textured, and bloomed.2 Look closely at the detail; is it so uniform as to be done by a machine? Or is there some variance in the texture? Was the piece polished so heavily it might have had another finish when it was first made? Is it an antique ‘bloomed’ finish or just a more modern sand-blast? Florentine finishes can help date your piece, while more abstract textured finishes might point to a certain designer.

Whether the appraiser uses a narrative to describe the item or a list model, the method of manufacture can be referenced any number of ways. Here are a few examples:

- Composed of cast and pre-fabricated components;

- Assembled from hand-fabricated components;

- Die-struck and assembled;

- Custom CAD/CAM and cast;

- Custom wax-carved and cast;

- Assembled from custom-cast and pre-fabricated components;

- Machined and assembled; or

- Mass-produced and assembled.

Practice and experience are required to recognize these various manufacturing methods. When starting out, take the time to examine known pieces; if you work in a jewellery store, examine the inventory. Become familiar with various companies’ methods of manufacture and memorize the way these pieces look. Working an auction preview is one of the best ways to examine antique and period pieces; see if there is an auction gallery in your area.

Detail is critical to compose a well-written appraisal. Not only can it elevate your appraisal documents above the competition, it greatly assists your client when they experience a loss.

Notes

1 The finish of a fine cast piece would have been given much more attention. Holes would have been thrummed (i.e. polished with a string), removing telltale signs

of that cast ‘skin,’ making this method more difficult

to detect.

2 Bloomed gold is the process of immersing the finished piece in a hot bath of hydrochloric acid, saltpeter, and salt and water to dissolve the alloys to bring the fine gold to the surface. This was extensively done up to the Victorian era, and is most prevalent in the art nouveau period. At that time, gold was alloyed with copper, and this process removed the pinkish colour of the piece. Another way to achieve this high-karat look is fire gilding; an amalgam of mercury and gold is applied as a paste to an object and then exposed to heat to vaporize the mercury. Both methods will only be seen on antique pieces.

[7]Carole C. Richbourg is an independent gemmologist/appraiser in Northern California and has been appraising full time since 1999. She is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist, and a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. Richbourg is co-instructor for the American Society of Appraiser’s (ASA’s) GJ-202 appraisal report writing for insurance coverage class. She may be contacted via e-mail at carole.richbourg@finejewelryappraiser.com.

[7]Carole C. Richbourg is an independent gemmologist/appraiser in Northern California and has been appraising full time since 1999. She is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist, and a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. Richbourg is co-instructor for the American Society of Appraiser’s (ASA’s) GJ-202 appraisal report writing for insurance coverage class. She may be contacted via e-mail at carole.richbourg@finejewelryappraiser.com.

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/OpeningImage.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/CAD_mouldAfterCastiing.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/ExamplePoorCasting.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/CIMG1719.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/1950sFlorentine.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Sawmarks.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Carole-C.-Richbourg.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/mastering-the-method-of-manufacture/