Meeting Cullinan: A jewellery appraiser’s unofficial guide to the famous diamond mine

by emily_smibert | February 13, 2017 9:32 am

By Carole C. Richbourg

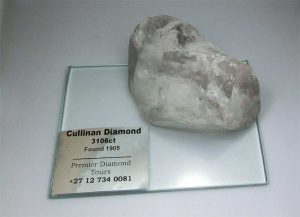

[1]The Cullinan diamond mine, historically known as the Premier, is situated nearly 40 km (25 mi) east of Pretoria in the small town of Cullinan. First established in 1902, the mine made its mark in history when, in 1905, the Cullinan Diamond was found. Weighing 3106 carats, it holds the record for largest rough diamond of gem-quality ever found. Today, the mine is owned by Petra Diamonds.

[1]The Cullinan diamond mine, historically known as the Premier, is situated nearly 40 km (25 mi) east of Pretoria in the small town of Cullinan. First established in 1902, the mine made its mark in history when, in 1905, the Cullinan Diamond was found. Weighing 3106 carats, it holds the record for largest rough diamond of gem-quality ever found. Today, the mine is owned by Petra Diamonds.

A walk through history

I arrive at the mine just in time to jump into coveralls, socks, and rubber waders, and catch my tour. I sling the backpack they provided over my shoulder, and join the group viewing a short film about the history of the mine.

Our small group has quite the assortment of international travellers with couples from Israel, France, and England represented.

[2]

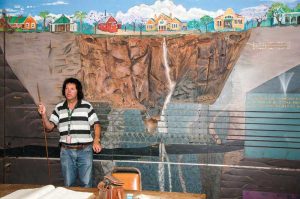

[2]We proceed to a large room containing interesting historical memorabilia, which include photographs and information about famous diamonds found in the mine over the years, [see sidebar] and antique memorabilia: old bottles, tools, an early movie projector, photographs, and other fascinating objects such as a large topical map of the mine spanning an entire wall. Unfortunately, we don’t have much time to look around, but I could have devoted another afternoon to these two rooms alone!

Safety first

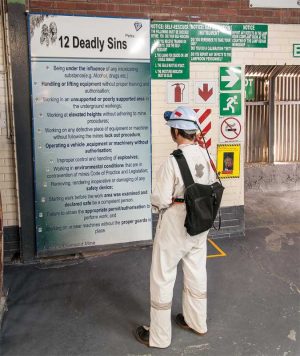

Before the group can proceed underground, for safety and liability reasons, the mine ensures visitors are briefed on safety procedures. The seven-step instructional video we view details how to use the breathing apparatus that will save our lives in the case of an explosion, accident, or accumulation of toxic gases. Gases in coal and gold mines are worse than anything we might encounter in a diamond mine. Even our guide, a stoic and competent gentleman named Henne, has never had to activate his kit—he started working in the mine, then under De Beers ownership, in 1958.

Upon completing the video, it is time to receive the last pieces of our equipment: a breathing pack, headlamp, and proximity beacon.

[3]

[3]Comings and goings

Trailing our guide, we walk a fair distance outdoors to the elevator cage which would take us 783 m (2568 ft) to the bottom. When De Beers owned the mine, the stated weight limit of this elevator was based on 106 people. However, when Petra acquired it in 2008, the load was reduced to 86 persons, as the weight of the equipment worn by the miners had not been taken into account.

We passed vast amounts of mined kimberlite, the rock closely associated with diamonds, which has come up from the mine; two large elevators draw up kimberlite 60 times an hour, 24/7, and long conveyor belts spanning metres carry the crushed kimberlite as it trundles along. The conveyor belts are flooded with water to further erode the sandy rock and expose any diamonds. The heavier diamonds sink to the bottom of the belt, so they aren’t washed away. This is after much larger pieces are crushed.

[4]

[4]While en route to the shaft, we’re told about new near-infrared spectroscopy and x-ray transmission imaging technology being used to mitigate damage of large valuable crystals. These developments are especially important for a mine such as the Cullinan, a source frequently yielding diamonds larger than 10 carats. The mine has produced more than 800 stones weighing over 100 carats, 140 stones weighing over 200 carats, and approximately a quarter of all diamonds mined weighing over 400 carats. In addition, Cullinan is the only reliable source for very rare and valuable blue diamonds. A new plant nearing completion has been built with the future in mind; this facility will continue to use and improve these modern tools.

The descent

Underground mining is the next step in extracting diamond-bearing rock once opened pits have become too steep, unsafe, or too expensive to work in.

We arrive at the cage, the only way in and out of the mine, and take the 2.5-minute long ear-popping ride underground alongside a full complement of working miners. When the heavy steel doors slide up and out of the way, a tired and dusty crew is waiting to go back up—miners work in shifts; 2 a.m. to 10 a.m., 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and 7 p.m. to 2 a.m. As the miners with whom we rode disperse into different tunnels, we stay near our guide so we don’t get lost.

[5]Inside Cullinan

[5]Inside Cullinan

To assuage those readers who might be a bit claustrophobic, once at the bottom, the mine feels surprisingly spacious, despite its rough walls and dim lighting. A thick layer of dust covers everything; the tunnels are lined with unused trolley tracks and there is ample room to accommodate large trucks and heavy equipment. Overhead, I can trace the colour-coded pipes bringing water and fresh air in, and the pipes clearing out carbon monoxide. In these tunnels, there are offices, break-rooms and refuge spaces, which are marked by amber light and easily found in the dark or emergency conditions.

Gone are the days of jamming sticks of dynamite into rock seams and running for cover. A clear non-volatile gel is mixed with another chemical and soon the mixture turns a thick, opaque blue. A carefully monitored electrical charge will activate this explosive.

We walk the tunnels, hewn of solid bedrock supporting the work to extract and push along the unstable kimberlite for processing. Once broken or blasted away, the kimberlite is dumped into ground-level chutes that funnel the rock to the two huge ore elevators. The elevators bring the diamond-bearing rock up to the surface where the process of crushing, washing, and sorting begins. Some of these older chutes, as well as much larger pieces of equipment, are rusty and decommissioned, but it isn’t cost effective to dismantle and remove them from the mine.

[6]

[6]Around these transfer points, we pick up and examine pieces of the kimberlite, also known as blue ground. The dark sandy rock is damp and crumbly, with shiny bits of chromite catching the light of our headlamps.

A memorable experience

The cage ride up to ground-level is silent; perhaps we’re all glad to be above ground, or maybe struck silent with a sense of admiration for the men and women working in the mines.

[7]

[7]We trek to see the view of Cullinan’s big hole, then return to the tourist centre and walk through the showroom where visitors can buy trademarked Cullinan Star Cut faceted diamonds. This proprietary cut is a round brilliant diamond with 66 facets. A certificate of provenance accompanies these goods as verification the diamond was mined here and can only be purchased at Cullinan Diamonds.

If you happen to come across a diamond like this in your own business, every stone is laser-inscribed with a unique identifier and accompanied by a Gemological Institute of America (GIA) diamond grading report. Also for sale? A replica of the famed Cullinan Diamond, which now sits proudly in my office as a symbol of the 783-m (2568-ft), 6000-step, and 4.8-km (3-mile) trek it took to conquer Cullinan.

[8]

[8]

| Other notable diamonds from the Cullinan Mine |

|

The Golden Jubilee; 1986 The Taylor Burton; 1966 The Blue Moon; January 2014

The Cullinan Dream; June 2014 |

Carole C. Richbourg is an independent gemmologist/appraiser in Northern California and has been appraising full time since 1999. She is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist, and a fellow of the Gemmological Association of Great Britain. Richbourg is co-instructor for the American Society of Appraiser’s (ASA’s) GJ-202 appraisal report writing for insurance coverage class. She may be contacted via e-mail at carole@finejewelryappraiser.com[11].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Hardhats1-IMG_3700_edit.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-_DSC9515.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-Untitled_Panorama2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-_DSC9565.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-_DSC9649.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-_DSC9577.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Diamond_Mine-_DSC9687.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CullinanReplica.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/BlueMoon.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CullinanDream.jpg

- carole@finejewelryappraiser.com: mailto:carole@finejewelryappraiser.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/meeting-cullinan-a-jewellery-appraisers-unofficial-guide-to-the-famous-diamond-mine/

[9]At 29.6 carats in the rough and 12.03 carats polished, this diamond was sold by Sotheby’s for $48,147,708 U.S. in Geneva on Nov. 11, 2015— a world record price for a fancy vivid blue diamond. (Author’s note: The diamond was purchased by a Chinese billionaire for his seven year-old daughter, Josephine, and renamed the Blue Moon of Josephine).

[9]At 29.6 carats in the rough and 12.03 carats polished, this diamond was sold by Sotheby’s for $48,147,708 U.S. in Geneva on Nov. 11, 2015— a world record price for a fancy vivid blue diamond. (Author’s note: The diamond was purchased by a Chinese billionaire for his seven year-old daughter, Josephine, and renamed the Blue Moon of Josephine). [10]Sold by Christie’s for $25,365,000 U.S. in New York on June 9, 2016, this 122.52-carat blue diamond in the rough and 24.18-carat polished diamond is the largest and most valuable fancy intense blue diamond ever auctioned. Among those in the audience was Mark Cullinan, an international jewellery dealer and the great-grandson of Sir Thomas Cullinan.

[10]Sold by Christie’s for $25,365,000 U.S. in New York on June 9, 2016, this 122.52-carat blue diamond in the rough and 24.18-carat polished diamond is the largest and most valuable fancy intense blue diamond ever auctioned. Among those in the audience was Mark Cullinan, an international jewellery dealer and the great-grandson of Sir Thomas Cullinan.