Mining in Myanmar: The road to Mandalay and Mogok

by carly_midgley | May 3, 2018 10:59 am

By Cynthia Unninayar

[1]

[1]Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem, “Mandalay,” evokes a sense of nostalgia for the adventure and exoticism Asia might have promised a British soldier. When I joined a small group of gem dealers and researchers embarking on an adventure of my own to Mandalay and the magical mining area of Mogok in Myanmar, I couldn’t help but share in its sentiments.

Historical significance

As part of an expansion into Asia, and with a keen interest in the rubies coming out of this region, the British conquered Burma after three Anglo-Burmese wars in the 19th century. The country gained independence in 1948, initially as a democratic nation, but following a coup d’état in 1962, Burma became a military dictatorship. For the next five decades, it endured oppressive military rule, ethnic strife, civil wars, and unrest.

In 2003, to put pressure on the military junta, the U.S. government initiated a trade embargo on all Burmese gemstones. There was a loophole, however. Stones faceted in another country (generally Thailand) could be imported into the United States as products of that country.

New legislation in 2008 closed this loophole and prohibited all Burmese ruby and jadeite from entering the United States. These gems were also banned by the European Union (EU). Other stones, including famed Burmese sapphires, were not included in the new law.

Despite the embargo by the EU and United States, the Burmese junta continued to sell gems to China (Myanmar’s largest trading partner) and India, among other nations. According to industry watchers, the ban mainly hurt small artisanal miners and gem traders who sold stones to Thailand’s gem merchants, while it reinforced the power of the large industry players and the military.

In 2012, the United States normalized its relations with Myanmar, and it removed the embargo on many Burmese products. The ban on ruby and jadeite still remained, however, because of serious concerns about the junta’s continuing involvement in human rights abuses and the revenue it generated from the jadeite and ruby trade. In October 2016, this ban was also lifted.

Gemstone haven

[2]

[2]

Photo courtesy Cynthia Unninayar [3]

[3]

Photo courtesy Ioannis Alexandris

After visiting the remarkable jade pagoda in Mandalay, my group began a six-hour, 200-km (124-mi) journey to Mogok. The road was narrow, and it wound through lush, jungle-covered mountains. Finally, we reached ‘Ruby Land’ and the bustling town of Mogok, nestled in the picturesque region of Upper Burma.

The gemstones in this area are found mainly in the Mogok Stone Tract at an elevation of 1170 m (3837 ft). This area is an important source of rubies as well as other gems, including sapphire, spinel, peridot, zircon, topaz, and garnet.

Rubies from Mogok have been prized throughout history; unheated gems in the coveted pigeon-blood-red colour range are among the most expensive in the world. The celebrated royal blue sapphires also come from this area.

Until the 19th century, mines were under the control of various Burmese rulers, with hardly any independent mining. In 1886, the British took control of the Mogok Stone Tract region and tried to mechanize operations. Ironically, some of the richest deposits were under Mogok, which lead to the relocation of the town.

In 1929, intense rains flooded the mines, and the resultant lake can be seen today in the centre of the small city. After gaining independence in 1948, the Burmese government continued to control the mines, and in 1969, the Ministry of Mines banned private exploration and mining, effectively nationalizing the entire gem trade.

Beginning in 2000, the government undertook joint ventures with private companies to mine gems on a profit-sharing basis. Currently, an estimated 1000 to 1200 gemstone mines operate in the Mogok Stone Tract. These include artisanal miners, co-operatives, semi-mechanized operations, and large-scale companies utilizing modern exploration and excavation techniques. Methods range from using open pits in secondary alluvial marble gravel (locally called byon) to tunnelling in primary host rock.

[4]

[4]Photo courtesy Cynthia Unninayar

Today, Mogok gemstone deposits are declining, especially alluvial deposits. This is leading toward more mechanization and drilling in the primary marble host rock.

One longstanding component of mining in Mogok is the custom of kanasé ma. After the sorting operations, some missed gems end up in the tailings. Local custom dictates tailings may be searched by anyone, who may then keep the gems they find. Most of these kanasé ma miners are women who break up the waste rock to find gems, thus providing a source of small stones for local markets.

A spiritual connection

[5]

[5]Photo courtesy Tasnara Stripoonian

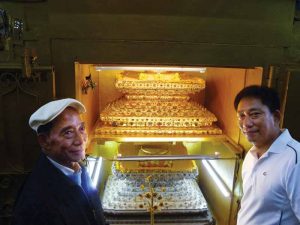

In Myanmar, 88 per cent of the population are practicing Buddhists, and since gemstones are a major part of life in Mogok, they are often used as offerings and decoration in the many pagodas and monasteries dotting the landscape. Perhaps the most extraordinary example of the link between gems and religion can be found in the beautiful Phaung Daw Oo Pagoda, which features an impressive white marble Buddha and two sacred gilded Buddhas surrounded by intricate patterns of mirrored walls and columns. The pagoda also houses two incredible gold and silver plinths, encrusted with thousands of gemstones of all types and qualities. Once a year, the two gilded statues are placed on remarkable gem-covered bases for public viewing.

My group also visited the large Chanthargyi Pagoda on the other side of the manmade lake in the centre of town. Along with beautiful statues and elaborate mirrored walls, the pagoda houses an elaborate collection of precious gemstones and art objects of all sorts, all donated by the local population.

Markets

Trading gems in Mogok has two basic formats. In the morning, several local markets open around the city, usually along roadsides or on designated streets. Buyers walk around and view gems laid out on small tables or even on the ground. Most sellers are women who come with traditional bronze plates and other trays full of rough and polished gemstones, fossils, old coins, and other objects.

We visited the Cinema Market. Comments from the gem dealers in our group indicated prices were high and a small number of fakes were seen, complete with fraudulent certificates. Yet, some group members did buy a few quality pieces.

[6]

[6]The second type of gem market is held in the afternoon, with dozens of tables sheltered by umbrellas. Here, buyers don’t walk around, but rather sit at a table and the sellers come to them. We spent an afternoon at the Blue Umbrella Market in central Mogok, one of the city’s largest. As soon as we sat down, dozens of sellers approached us, eagerly showing their stones. Most were either too expensive or of poor quality, although some good deals were made.

The local population uses lower-quality gemstones to make artisanal products, including a wide variety of paintings made from crushed gems of all colours. These are on sale at many of the gem houses in Mogok.

Mines

[7]

[7]

Photos courtesy Cynthia Unninayar [8]

[8]

Photo courtesy Saengthip Saengbuangamlam

Mines of all sizes mark the landscape in the greater Mogok area. Peridot is mined in the Shan Hills around Bernardmyo, northwest of Mogok. Named after Sir Charles Bernard, British Commissioner of Upper Burma, the town sits at an altitude of 2000 m (6560 ft) and was established as a military sanatorium and station following the Third Burma War (circa 1887). The British abandoned it around 1900.

A few kilometres from Bernardmyo is the Nanda Aung peridot mine. Gem material is brought out of the mine through narrow tunnels, and is then transported elsewhere for washing and sorting.

The largest sapphire mine in Mogok is Baw Mar. Opened in 1993, it combines both open-pit mining and tunnelling. Over the last decade, it has produced some exceptional gems, up to 10 to 15 carats. The mine’s largest stone was 2000 carats, but it was so dark it had to be broken apart to find lighter colours. During the rainy season, the mine employs around 80 people, while in the dry season, more than 180 miners are at work. It has its own sorting and cutting facilities.

The owner of Baw Mar, Ye Minn Htoon, called Ko Choo, also owns a ruby mine nearby and manages gem auctions, which are held every three months for two days to allow buyers to examine the gems and submit written bids.

The largest ruby mine in Mogok is the privately owned Yadana Shin mine. With eight shafts, it employs 10 people per shaft, with three shifts a day. The holes are around 300 m (984 ft) deep, and the only way to get to the bottom is to climb. It takes a miner about an hour to make the descent and ascent on narrow vertical wooden ladders. The gem material is brought to the surface in rubber pails via pulleys. It is then crushed, washed, and sorted. The employees are paid by salary, by receiving a percentage of the sales of rubies, or by a combination of both.

Another large mechanized mine is Ruby Dragon, a joint venture with the government’s Ministry of Mines. It has a complex tunnel system at varying depths, but rubies are found at around 90 m (295 ft). The largest ruby found here was a 315-carat stone that sold for €570 million.

Indeed, Kipling’s poem was an apt reminder of the wonderful adventure our group enjoyed on this trip, made even more memorable by the kindness of our Burmese hosts and the people we met on the road to Mandalay and Mogok.

[9]A 20-year veteran of the jewellery and watch industry, Cynthia Unninayar travels the world reporting on the latest trends, promising new designers, global brands, and market conditions. Her interviews with some of the industry’s top players offer insight into what’s new and what’s happening on the global jewellery stage. Unninayar can be reached via e-mail at cynthiau@gmail.com.

[9]A 20-year veteran of the jewellery and watch industry, Cynthia Unninayar travels the world reporting on the latest trends, promising new designers, global brands, and market conditions. Her interviews with some of the industry’s top players offer insight into what’s new and what’s happening on the global jewellery stage. Unninayar can be reached via e-mail at cynthiau@gmail.com.

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/4-entrance-P1090657-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/5-mogok-lake-IMG_2878-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/15-Yannis-spinel-IMG_0014-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/6-phaung-daw-oo-P1090710-v1.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/7-GIT-IMG_0625-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/12-ruby-sorting.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/9-panorama-IMG_2868-copy.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/8-peridot-GIT-IMG_0766.jpg

- [Image]: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/mining-headshot-P1090272.jpg

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/mining-in-myanmar-the-road-to-mandalay-and-mogok/