Multiple deadlines: A jeweller’s nightmare

by charlene_voisin | August 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Tom Weishaar

[1]

[1]

Editor’s Note: This is the fourth instalment in a six-part series on creating custom jewellery. Over the course of the year, we’ll share the processes the author’s store went through to develop custom sales. We’ll also show you the methods used to create six custom pieces.

Many people have nightmares about things like spiders, snakes, or falling. Being a custom bench jeweller, my nightmares tend to be a bit different. Missing due dates, stones breaking, and rings melting are what keep me up at night. Nothing is worse for me than to have a sales associate tell me a customer is in the store to pick up their ring and I haven’t finished setting the stones yet.

We have a wooden box in the store where incoming repair jobs are placed. When I first started here, all the salespeople (employers included) would write ‘ASAP’ in the space marked ‘due date.’ This practice just would not do, and it took me several years to break the more hardcore individuals from doing this. That same box now has a sign that reads: ‘Jobs without due dates won’t get done on time.’

Holiday plans

[2]

[2]Like most bench jewellers, I am a fussy person who likes to have a plan for everything. The holidays are a bench jeweller’s busiest time of the year. In anticipation of the rush, I try to get myself even more organized.

Starting in October, I prioritize my work. Anything that can be put off until January goes on the back burner. Incoming jobs that only sell metal and labour, like repair work or remounting a customer’s older family stones, are divided into two categories: quick and easy or slow and laborious. The customers with the labour-intensive jobs are told in advance their items may not be completed before the holidays, while the quick and easy ones are pushed through. Finally, jobs that sell expensive gemstones are given the highest priority. It’s unfortunate, but this busy time is all about pleasing the most people and maximizing the store’s sales.

Needless to say, I was dumbfounded last November when my employer took in the most time-consuming job I’ve ever attempted and promised it would be done in time for the holidays. In his defence, he said I had 54 days to complete the job, so what’s the problem, he asked? The problem was this job would require more than 150 hours to complete, not to mention the fact we did not have the technology to make it happen, and three other time-consuming jobs were in the queue.

Let the nightmare begin

[3]

[3]The massive project before me was an example of an emotional type of sale, where items are being passed down after a death in the family. The client’s father was a professor of geology. During his summers off, he liked to take his family on vacation to Montana to visit the Yogo sapphire mine. The whole family would enjoy a week digging for sapphires, and he would spend the winter months practicing gem faceting on their finds.

The father passed away last summer and his daughter inherited a large handful of custom-cut and very unique sapphires. Her request was to create a special necklace using as many of the sapphires as possible. Over the next two weeks, the customer worked almost daily with our store’s designer to arrange the sapphires in just the right pattern. Over this same period, I was given the task of coming up with a plan for making the necklace.

Technology—solutions and problems

[4]

[4]A necklace by definition incorporates a chain or some other holding device directly into the piece. It is much more difficult to create than a simple pendant, which is merely suspended from a chain. Â

Our customer chose a 6-mm white gold collar around which to build her special necklace. She also wanted the necklace to be 19 in. long. I photographed the correct length collar lying on her neck so that I could see the exact curvature from both side and front views. These images were then transferred into the computer. Using CAD, I was able to recreate the collar and thus construct the necklace around the image.

With the collar model created, it was time to tackle the necklace. The design called for 116 sapphires and 14 diamonds to be methodically placed into individual crowns that would then appear to be a solid band of colourful stones. I was first told to join each of the crowns together using tiny jump rings. This seemed impossible, given the desire to keep all the stones tightly packed together, not to mention it was a ridiculous amount of work. I argued for creating seven separate segments that would be hinged to allow the necklace to move as the neck moved. I won the argument, but on the condition the hinges be hidden behind the stones.

[5]

[5]Time was ticking as I set to work—14 of my 54 days were already gone. Each new day was divided among the jobs I already had scheduled and working on the sapphire necklace.

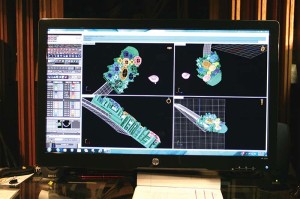

CAD technology proved invaluable when it came to designing the crowns for each custom stone. By capturing an image and projecting it on the computer screen, I was able to recreate each of the stones in a digital format. Once the stones were digitized, I made a customized crown to fit these small odd balls. I have often spoken that I have a love-hate relationship with CAD/CAM. For this job, I can tell you honestly that I loved it.

The quote

We were three weeks into our project when I finished the CAD design for the first of the necklace’s seven sections. This was a significant turning point for two reasons. First, we still did not have an accurate estimate assigned for this project. Until I could determine how the piece was to be made and the amount of labour needed to produce it, I could not judge how much it would cost. The first section took seven hours of CAD time to design. Based on that, I estimated the necklace would take 50 hours to design, 15 hours to manufacture, and 90 hours to set the stones. That’s 155 hours, and Christmas was just six weeks away.

New technology to the rescue

[6]

[6]My second concern was even worse. Milling machines are great for most design projects. They are fast and inexpensive to operate, but they can have difficulties cutting out recesses or hidden spaces. My design called for creating seven multi-basket-style sections. These would each have many hidden areas that our mill could not reach. I tried several times to come up with a method to mill the first necklace section. I decided to divide the section into an upper and a lower segment. My plan was to join the two sections together and then cast it as a single unit. I even went so far as to cast a practice model, but the results were poor. A new solution was needed.

The store’s management team had been discussing the possibility of purchasing a 3-D wax printer (also known as a grower) for the past year. This particular design helped cement our decision—we ordered the machine.

Don’t you love getting new stuff?

[7]

[7]While the 3-D printer was being shipped, I used the time to work on the CAD designs for the necklace’s other six sections. The grower arrived in late November and I was only finished with five of the seven sections. Projects were coming into the store quickly, and I could not devote all my time to just the necklace. The machine was quickly tested and then immediately put to task growing the waxes for different projects. During the first three days, everything went well with the printer, but problems arose on day four. The manufacturer ran remote tests on the machine via the Internet for several days. Ultimately, a technician was flown out to access our situation. Heat was the problem. We had placed the grower in a south-facing room that had a big window. During the day, the sun beat down directly onto the grower, throwing off the machine’s temperature calibrations and ruining its sensitive printer heads.

This could have been a sad story, but the manufacturer was fabulous. We returned the old machine, while a new one was in transit—time was the only cost to us. When the new grower arrived, it was moved to a much cooler section of the building and I am now very careful about monitoring its temperature settings. Since then, the grower has worked flawlessly.

Assembling and setting

You can see in the opposite bottom photo the grower did a great job of creating the individual sections. They each cast perfectly and fit together like seven gloves. At this point, I mistakenly thought I had cleared all the big hurdles in creating this project. My only problem now seemed to be time. The delay with the grower had cost me more than a week’s time, however, I was able to complete other projects in the queue. With a clear calendar before me, it was time to start setting the sapphires.

The last hurdle—a huge mistake

[8]

[8]In my haste to design the necklace, I had forgotten completely how oddly shaped the sapphires were. They had been cut by someone who was just practicing the art of faceting; he may not have ever intended for them to be set. In some cases, the girdles were a full two millimetres thick. Many of the stones, like the pale blue sapphire in the top photo on page 4, had 80-degree pavilion angles. Unfortunately, I had made the error of using the CAD program’s default settings to adjust the basket crown’s prong height. The prongs were in many cases too short to reach over the top of the stone’s girdle. Where appropriate, I was able to add metal to the prongs’ tips, but in some cases, I had to rebuild and recast several of the necklace’s sections. It goes to show you are never too experienced to make mistakes.

I was completely blown away by how accurately the growing machine created the six hinges that were to be hidden behind the sections. They fit together remarkably well. I had built tiny stops into the hinges so the sections could not open forward. This was done to prevent the stones that were tightly spaced from bumping into each other. It all worked beautifully! The only thing I had to do was to use a watchmaker’s cutting brooch to ream out the insides of the hinge tubes. After that, the rivets fit perfectly and I hammered their tips flat to lock everything in place.

The final step was to cut the collar in two pieces and solder sections ‘one’ and ‘seven’ to it. Since I had designed end caps for these end sections, the collar slipped right inside the cap and a small amount of easy-flow solder was used to seal it in place. It felt so good to finish this project.

A bittersweet ending

[9]

[9]Our customer loved her new necklace. She cried for a long time when she saw it. She just kept touching it and saying things like, “Dad would be so proud of this. I wish he could be here to see it.” With the redos, the necklace ended up taking a total of 170 hours to complete. That was 15 hours longer than I had anticipated. I finished the piece on Dec. 28. For only the second time since becoming a bench jeweller, I had missed a Christmas deadline.

This article was important to me to write, not because I enjoy discussing my mistakes. On the contrary, I rarely, if ever, like to admit to making an error. I wrote this because I very much want younger bench jewellers to understand they are never old enough and never smart enough to prevent every error. As bench jewellers, we can’t know what project will come through the front door next, and we can never know the perfect method to conquer each one. That’s both the frustrating and the exciting aspects to our careers. Instead, we should try to learn something from each job. Some of those projects might temporarily beat us up, but the real error is to allow them to beat us down.

For the next issue, I’ll be back on safe ground discussing a star-studded pavé project. I hope you’ll join me.

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tsweishaar@gmail.com[11]

[10]Tom Weishaar is a certified master bench jeweller (CMBJ) and has presented seminars on jewellery repair topics for Jewelers of America (JA). He is an award-winning columnist, picking up Silver at the Kenneth R. Wilson awards for his six-part series on stone-setting techniques. Weishaar can be contacted via e-mail at tsweishaar@gmail.com[11]

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/dreamstime_m_30194945.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-01.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-09.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-12.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-11.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-14.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-15.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-16.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Custom-17.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Tom-Weishaar.jpg

- tsweishaar@gmail.com: mailto:tsweishaar@gmail.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/multiple-deadlines-a-jewellers-nightmare/