New horizons: How fresh discoveries push the gemstone industry forward

By Lauriane Lognay

As a writer and, most importantly, as a gemstone wholesaler, I try to keep up with all the new discoveries, treatments, and price fluctuations happening in the gem industry. The gemmology world is a scientific community, bent on learning everything there is to know about every gem there is to discover. Each year, at least 50 new minerals, rocks, and gems are discovered. They vary in importance, and not all are gem quality or even useful, so of those 50, only one or two at most make it into the jewellery market.

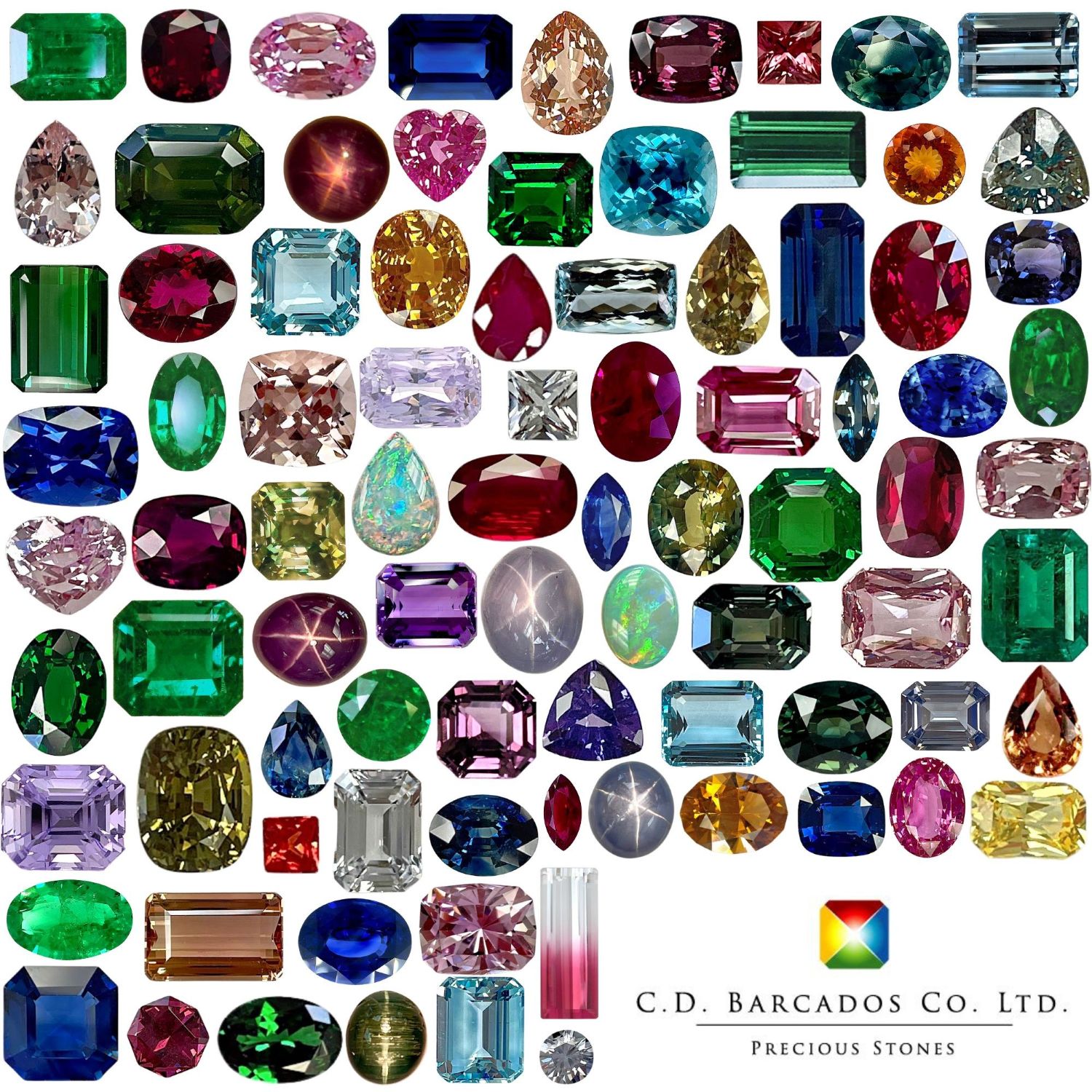

Discovering new varieties and new gems is always exciting for jewellers and for our clients. Customers get to have more choice, more colours, and a bigger price range for gems. Looking for green? No problem—we have 10 gems from which you can choose. Looking for a certain price? No problem—we have three options for you! The more we discover, the more possibilities we can present.

Even better are the cases where the discovery is a new variety of an existing stone, because we already know a lot about the gem, its hardness, and how to work with it on the bench. We simply get to enjoy a new colour.