Pretty in pink: How origin reports for pink diamonds may affect their value

by charlene_voisin | August 1, 2014 9:00 am

By Branko Deljanin

[1]

[1]

Natural near-colourless diamonds originate from more than 10 diamond-producing nations whose mines are owned by several big mining companies, including major players like Alrosa, Dominion Diamond Corp., De Beers, and Rio Tinto. In addition, many other primary and alluvial deposits are sporadically mined by smaller companies, and in some instances, by family businesses in places like Brazil and Africa.

If any of these mines ceased operation, the world’s market value of near-colourless diamonds would likely not be affected. In the case of pink diamonds, however, 90 per cent of the world’s supply is mined from a single source—Rio Tinto’s Argyle mine in Australia.

Although operations at Argyle are currently underground, the mine’s production life is expected to run until approximately 2020. This limitation, combined with the rarity of pink diamonds to begin with, is a contributing factor to skyrocketing prices. There is a 15 to 30 per cent premium on pink diamonds with proven Argyle origin, and efforts are currently underway to establish a means of tracking (and identifying) these stones to their origin. Although the Argyle grading system for pink diamonds has been around for some time, Canadian jewellers are increasingly using these stones in their designs (particularly ranging from .01 to .30 carats) and an overview may be required.

Golconda diamonds

[2]

[2]Historically, there are diamonds that command higher prices simply due to their specific origin. Golconda stones are one example. Sourced from a geographical area in India of the same name, these diamonds are of the Type IIa variety, which accounts for less than two per cent of the world’s diamonds.

Today, authentic Golconda diamonds are extremely scarce and are found mainly in museums or in collections with roots going back to the 17th century. Occasionally, such stones with a provenance letter from a recognized lab may come up at auction, but that happens rarely.

Over time, the term ‘Golconda’ has evolved to describe diamonds with the same high level of transparency, clarity, and colour (known in the trade as ‘D plus’). Since the 1980s, the Gübelin Gem Lab has issued a Golconda Appendix as an addition to its grading report for “exceptional diamonds that show a combination of rare properties, such as an antique cutting style, as well as superior colour and clarity. These stones also must qualify as Type II diamonds, free from nitrogen and therefore chemically pure.” A small percentage of them are also blue or light pink in colour.

The rarity of pink diamonds

[3]

[3]Blue and pink diamonds (especially when they are saturated enough to be graded fancy red) are considered the most expensive natural creation by weight in the world. After India’s major production of diamonds began in the 17th century, Brazil was the next primary source for colourless and coloured diamonds, including rare pink and blue stones originating from the panning of gravel in its rivers.

It was in one such small river that a local boy found a red 13.90-carat diamond crystal while swimming. In 1990, the crystal was purchased by William Goldberg Diamond Corp., and cut to produce a 5.11-carat fancy red, the largest of its kind. In 2001, it was purchased by Moussaieff Jewellers for $1.8 million USD per carat and re-named the ‘Moussaieff Red.’ Originating from approximately one gram of carbon that turned red as a result of a perfect combination of pressure and temperature, the stone is currently valued at more than $9 million USD.

At 59.60 carats, the flawless ‘Pink Star’ was offered at auction for $83 million USD last November. Although it carried a GIA report indicating it is a Type IIa fancy vivid pink, there was no provenance information. Based on our research, Type IIa pink diamonds are generally sourced from India, Brazil, or Africa, and not Australia, Canada, or Russia, as stones from these areas are all Type Ia and contain nitrogen.

The following are known sources of pink and purple diamonds and their claim to fame regarding important stones:

- India (Golconda—the 28.15-carat ‘Agra’ pink diamond);

- “¨Brazil (Minas Gerais—the 5.11-carat ‘Moussaieff Red’);

- South Africa (Premier mine, also the source of blue diamonds; Cullinan mine is a source of large Type IIa diamonds);

- “¨Tanzania (the 23.60-carat ‘Williamson Pink’);

- Russia (Siberia—mostly purple diamonds);

- Australia (Argyle mine—.95-carat ‘Hancock Red,’ first gem to be sold for $1 million per carat); and

- Canada (Northwest Territories [Diavik mine], some pinkish-purple diamonds; and Northern Ontario [Victor mine], pink).

Pink diamonds appeared only sporadically in jewellery until the discovery of the Argyle mine. In the mid-1980s, it became the first mine ever to produce a steady supply of fine melee (up to .10 carats) and small pink diamonds (less than one carat), along with rare one-carat-plus pinks. The new mine supplied enough volume to make pavé setting possible with pink diamonds.

Since it was commissioned in 1985, Argyle has produced more than 800 million carats of diamonds—less than 0.1 per cent has some pink colouration. To offer some perspective, the entire annual production of pink diamonds greater than .50 carats could fit in the palm of your hand and represent 10 per cent of the value of all Argyle diamonds. The rarest pink and blue diamonds are sold at annual tenders in major cities around the world to a select group of diamantaires.

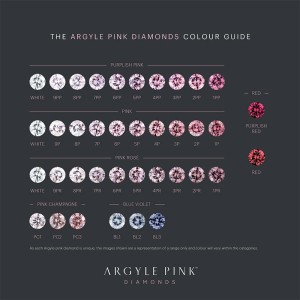

Argyle’s diamond-grading system

[4]

[4]In order to accurately grade brown, pink, and blue diamonds from Argyle, Rio Tinto developed its own grading system, which is substantially different from Gemological Institute of America’s (GIA’s) and thus, very difficult to correlate grade to grade.

The grading of these diamonds at Rio Tinto’s Perth facility is very strict, often one clarity grade lower than other international labs. The Argyle colour system is very specific, using more categories than GIA. However, the only drawback is that it is made specifically for Argyle-mined diamonds and is difficult to apply to coloured diamonds sourced elsewhere. Pink diamonds with orangey modifiers from Brazil are one example; the Argyle system simply does not have an option for this colour.

Within the Argyle grading system, pink diamonds are classified into three categories according to hue:

- purplish-pink (PP);

- pink (P); and

- pink rose (PR).

Each category ranges in intensity from ‘1’ (the most intense) to ‘9’ (the lightest). Stones classified as 1PP (intense purplish-pink) are generally the most expensive. The other three colour categories typically found at Argyle are: pink champagne (PC), blue-violet (BL1 ““ BL3), and red, which is the rarest colour of diamond found at Argyle.

Pink champagne (PC) colours are primarily brown diamonds with a pink secondary colour. Stones with a brown hue and pink modifier are graded using the following colour grades:

- PC1: pink champagne light;

- PC 2: pink champagne medium; and

- PC 3: pink champagne dark.

It is important Canadian jewellers be familiar with Rio Tinto’s colour grading system—all Argyle ‘better pink’ diamonds greater than .15 carats sold after 2009 are lasered with the mine’s logo and often don’t carry GIA or HRD reports.

Clarity is not as important as colour in the valuation of Argyle pink diamonds, as these stones are usually SI or I due to many inclusions, most often graphite and fractures.

Changes in certification?

[5]

[5]Over the last five years, demand for pink diamonds has increased due to the following factors:

- Ҭexposure in mainstream media, most often in the form of major celebrities buying pink diamonds, as well as record-breaking prices at major auctions;

- “¨Australia’s strict adherence to the Kimberley Process; and

- the overall rarity of pink diamonds.

As a result, pink diamonds are increasingly sought-after items at major gem and jewellery shows, with buyers often paying a premium when accompanied by paperwork proving Argyle origin.

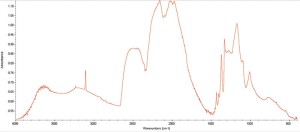

In 2007, this author began a research project in conjunction with an international team on the characterization of pink diamonds of different origin. It found Argyle stones exhibit fluorescence under a UV lamp that corresponds to typical visible spectra and a characteristic ‘fingerprint’ in the infrared part of the spectra. While rare Golcondas are Type IIa, Argyle pinks comprise nitrogen and typically more in ‘B’ form than ‘A,’ making them Type IaAB. In collaboration with our lab, Gem Research Swisslab (GRS) in Hong Kong is also accumulating data on pink diamonds from different sources using advanced spectroscopy.

Results of this research could fundamentally change the certification process for pink and blue coloured diamonds that due to their source, share similarities with rare rubies or sapphires. Coloured stones have always been sold based on origin—consider Burmese rubies or Kashmir sapphires, for example. For diamonds, the opposite is true, although there is a possibility origin may soon be included on grading reports.

Trading rare diamonds in Canada

[6]

[6]The rare 2.74-carat light pink seen on page 1 is an SI1 and one of the largest Canadian pink diamonds unearthed to date. Originating from De Beers Canada’s Victor mine, the diamond was cut and polished at Crossworks Manufacturing’s facility in Sudbury, Ont., into an oval shape to maximize its weight.

Rare diamonds do not always cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and are not only sold at auction. ‘Faint’ and ‘pale’ pink diamonds (i.e. fainter than 7P on the Argyle scale), as well as ‘light pink’ (i.e. approximately 7 to 8P), have slowly made their way into jewellery design over the past couple of years in Canada. Colour saturation is the most important factor in determining the value of pink diamonds, so clarity may vary from eye-clean to very included. A greater number of designers are choosing these more affordable diamonds, as they can be suited to many designs while still retaining an air of rarity.

Due to effective marketing of rare diamonds, more and more private buyers in Canada are buying not only large and clean ‘champagne’ and ‘cognac’ or intense yellow diamonds, but also more expensive .30-carat-plus fancy to intense purplish-pink stones for investment purposes.

These days, consumers are very conscious about the origin of products. In addition to demanding fair trade coffee and other products, it is reasonable to expect a similar interest in knowing where their coloured diamond comes from. Canadian wholesalers and jewellers should be ready to provide the answer.

A rosy future

[7]

[7]The science of gemmology is evolving and more advanced instruments are being used in gem labs for routine testing of diamonds and coloured stones to determine whether something is natural, treated, or synthetic. In addition, a few specialized labs are also offering country of origin reports using advanced testing (spectroscopy and chemistry), a high level of expertise, and an extensive collection of rare gems from different mines and countries with which to compare.

In the last few years, the market has seen increasing interest in provenance for rare coloured diamonds, especially pinks. Similar to the way important rubies are sold at shows and major auctions with origin reports, only time will tell whether Argyle pinks (and possibly other colours) will follow the same trend.

The author would like to thank Adolf Peretti of Gem Research Swisslab (GRS), John Chapman of Rio Tinto Diamonds, and Bill Vermeulen of CGL-GRS Swiss Canadian Gemlab for their contribution to this article.

[8]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and director of CGL-GRS Swiss Canadian Gemlab Inc., in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines, and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[9].

[8]Branko Deljanin, B.Sc., GG, FGA, DUG is head gemmologist and director of CGL-GRS Swiss Canadian Gemlab Inc., in Vancouver. He is a regular contributor to trade and gemmological magazines, and has presented reports at a number of research conferences. Deljanin is an instructor of standard and advanced gemmology programs on diamonds and coloured stones in Canada and internationally. He can be reached at info@cglworld.ca[9].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Victor-Pink-Diamond-Ring.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Underground-mining-at-Argyle-will-extend-mine-life-for-another-7-years.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/The-author-with-A.-Peretti-GRS-at-Argyle-mine-in-2014.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/tiara.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Argyle-Pink-and-Blue-Diamonds-Colour-Chart.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/All-Argyle-diamonds-fluoresce-strong-blue-under-LW-fluorescence.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/typical-infrared-spectra-of-brown-pink-diamond-from-Argyle.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Branko.jpg

- info@cglworld.ca: mailto:info@cglworld.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/pretty-in-pink-how-origin-reports-for-pink-diamonds-may-affect-their-value/