Provenance as a value element

by charlene_voisin | July 1, 2014 9:00 am

By Mark T. Cartwright

[1]

[1]

Provenance—as defined as the association of an item to a renowned designer, maker, or even a famous owner—can have a significant influence on value”¦ sometimes. Whenever it exists, it represents an extrinsic property that should be considered in the valuation process; however, before it becomes part of the equation, it needs to be corroborated beyond a reasonable doubt.

With a ‘signed’ piece, it is a matter of verifying the signature isn’t a forgery and its details are consistent with the designer/maker. In some cases, it may be necessary to contact the artist directly because only they can state claims of authenticity as a matter of ‘fact.’ As appraisers, we can only provide an opinion of authenticity; for that opinion to be credible, we need supporting evidence. However, when working with items that aren’t signed, or which are simply claimed as having once belonged to a famous individual, the process of gathering sufficient evidence can become much more difficult and time consuming.

Unlike an intrinsic detail, such as a gemstone’s carat weight that can be proven simply by observation, provenance is an extrinsic value element that can only be shown to exist by documentation. Whenever we consider provenance in our valuation, we should also provide the evidence upon which we base our opinion. I’ll use an example from one of my assignments to help illustrate the extent of research that may be necessary when trying to find enough support for attribution as a value element.

Just a brass pot?

[2]

[2]It began when I received a call from a fellow appraiser asking if I’d ever heard of Paulding Farnham. My colleague is a fine art specialist and her client had several pieces of jewellery attributed to Farnham that he wanted appraised. As good fortune would have it, I was very familiar with Paulding Farnham and had, in fact the year before, completed an appraisal of several pieces of jewellery he’d designed. My colleague referred her client to me. For those readers unfamiliar with Paulding Farnham, he was the lead designer at Tiffany & Co., from 1891 until 1902. His designs swept the gold medals at the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and 1900, which some believe effectively established the retailer’s reputation as a worldwide force in the luxury markets.

In the course of our conversation, the client indicated he was having household contents appraised in a specific order; before the jewellery, he wanted a brass pot appraised. I referred him back to my colleague, although she had already declined the job. I then suggested another appraiser who specialized in residential contents, but he declined. I explained to the client it was beyond my area of expertise, but I would be willing to assist him only if he would permit me to bring in any necessary experts, allow sufficient research hours, and accept I would state in the appraisal the assignment was beyond my expertise and the specific steps I took to ameliorate that concern. He said the item probably wasn’t a big deal—it had been in the foyer of his home for decades and just looked like a brass pot to him. An appointment was made and I was left puzzled by his rationale for having a brass pot appraised at considerable expense.

He arrived at my office with a large object in a blanket that didn’t quite conceal a realistically rendered 3D silver bird peeking from the wrapping. Once the piece was safely inside and unwrapped, I was stunned. Sitting on my desk was a 406-mm (16-in.) tall vase created from a single piece of silver and copper Mokume-gane covered with engraved images and appliqué, including a high-karat gold representation of the Provincial Seal of British Columbia”¦ and there was that silver bird perched on the rim! Even though the surface was heavily tarnished, it was clear this was an extraordinary piece. Once again, I attempted to extract myself from the assignment as I explained to the client this was not the ‘simple brass pot’ he’d described over the phone and was very likely an extremely valuable item that was going to require significant research. He’d driven more than 320 km for the appointment and was in no mood to take no for an answer. We came to an agreement concerning the intended use of the report, scope of work, and fee structure; he left and I called my insurer to increase loss coverage and made room in my safe for the vase.

Where to begin

[3]

[3]As I began the process of evaluation, it was obvious that being able to attribute this item directly to Paulding Farnham was going to be extremely important to the value conclusion. Unfortunately, all I knew as a fact was that the current owner was a direct descendant of Paulding Farnham. Careful examination also showed it was not signed by Farnham or by Tiffany & Co. Instead, there were five other names stamped onto the bottom of the piece that I didn’t recognize. The design, finish details, execution, and materials were all consistent with Farnham’s work during his tenure as lead designer for Tiffany & Co., but without a signature, it would be difficult to convincingly attribute the piece to him without further evidence.

I contacted one of the leading authorities on Tiffany & Co., hollowware; they agreed it “looked right,” but there were no records in the company’s archives of anything like it. I contacted leading experts in Mokume-gane and was told that in 30-plus years of study, they’d never seen or heard of a raised Mokume-gane vessel of this size; in fact, they’d heard of nothing of this size in North America. One of the experts did offer that only Tiffany & Co.’s workshops were producing Mokume-gane in-house during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. That was interesting, but I needed to look for evidence in the piece itself. There was an astrological chart engraved on the vessel with a significantly oversized moon symbol. A crescent moon of this exact shape was a secret symbol used as an expression of affection between Paulding Farnham and his wife, Sarah (Sally); again, interesting, but not conclusive. There was a compass rose applied to part of the vessel, along with numerically expressed latitude and longitude that correlated to a location in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia, which tied in with the provincial seal. At last, a clue!

Finding public and private documents

[4]

[4]In my previous study of Paulding Farnham’s life, I recalled that during the late 1890s and extending into the early part of the 20th century, he was enthralled with mining in the western United States and Canada. During my previous assignment involving Farnham, I’d come across the Sally James Farnham Catalogue Raisonné Project, so I contacted the curator. He most graciously sent some family photos of Sally on horseback at the couple’s ranch in British Columbia. I began pouring through local newspaper archives, along with census, business, and mine records from the turn of the century. After many hours and many dead ends, I finally struck pay dirt!

I found occasional references to the Ptarmigan Mine and mining records indicating partial ownership by “a Mr. P. Farnham of New York.” Aha! The bird was a ptarmigan and the map co-ordinates for the mine matched those on the vessel. I also located an article in the Oct. 30, 1902 edition of the Victoria Daily Colonist archives announcing the naming of several peaks in the Selkirk range, including one Mount Farnham. The article states “”¦ known by several names among the prospectors, is now to be known as Mount Farnham in honour of Paulding Farnham of New York, promoter of the Ptarmigan Mines of the Selkirks”¦ Mr. Farnham’s property lies at the base of this mountain, and it is indeed well-named, for Mr. Farnham has greatly contributed to the development of the mines in this district.” Interestingly, his ‘contributions’ ended up costing him his fortune and his marriage, but that’s another story.

[5]

[5]Armed with this information, I located the Ptarmigan Mine’s production records and found it primarily produced copper and silver, with very minor recovery of gold. When I estimated the percentages of those three metals in the vessel, it appeared to match the ratio of copper, silver, and gold during the mine’s peak output in 1902. This correlation was later confirmed by documents that surfaced several years after my appraisal was delivered. At that point in the research, I had circumstantial evidence that linked Paulding Farnham, the map co-ordinates, the bird on the rim, the provincial seal, and possibly the composition of the vase, but was there more?

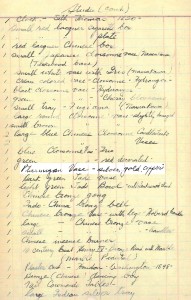

Again, I contacted the Sally James Farnham Catalogue Raisonné Project and after a diligent search, the curator located two documents. One was a handwritten inventory by Sally Farnham prepared when she moved to a new apartment in New York that listed among the studio contents an item simply described as “Ptarmigan vase”“silver, gold, copper.” This established ownership. The second document was key; it was Sally’s list of personal items and how they were to be distributed to the children. It provided a description and name of the artist for numerous pieces and included the entry “Ptarmigan Vase (Paul Farnham).”

Based on my now ‘considered’ opinion of attribution, I was able to conduct market analysis to arrive at the requested valuation for my client, after which, I assisted him in placing it in the right auction environment. As a magnificent, if quirky, turn-of-the-century Mokume-gane vessel, the piece might have brought $20,000 to $30,000 US in an active auction. Based on attribution to Paulding Farnham and the historical importance of the piece, it was sold at auction for more than $650,000 US.

Due diligence and consent

I hope this example provides readers with an idea of the depth of research that can become part of the scope of work when it is warranted by the potential difference in value. Anytime it becomes clear that providing credible results will involve significant research, it’s important to consult with the client and obtain their permission to expand the process and add billable hours.

Any readers wishing to see the Ptarmigan Vase in person may do so at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

[6]Mark T. Cartwright is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist appraiser (American Society of Appraisers), independent certified gemmologist appraiser (American Gem Society), and GIA graduate gemmologist, who has provided gemmological and jewellery appraisal services since 1983. He can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[7].

[6]Mark T. Cartwright is an accredited senior appraiser, master gemmologist appraiser (American Society of Appraisers), independent certified gemmologist appraiser (American Gem Society), and GIA graduate gemmologist, who has provided gemmological and jewellery appraisal services since 1983. He can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[7].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Americana-lot-114-Ptarmigan-Vase.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ptarmigan-vase-base-detail-1.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/ptarmigan-vase-compass-rose.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Farnham-documentation-from-SFCRP-2.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Farnham-documentation-from-SFCRP-4.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Mark-Cartwright.jpg

- gemlab@cox-internet.com: mailto:gemlab@cox-internet.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/provenance-as-a-value-element/