Something seems amiss: Synthetic diamonds amongst us

by charlene_voisin | August 1, 2013 9:00 am

By Mark T. Cartwright

[1]

[1]Recent trade news reports of discoveries of undisclosed synthetic diamonds may be indicators of uncertain times ahead for the appraiser/gemmologist.

Lab-grown diamonds have been around for decades. However, new developments in the technology necessary to produce them appear to have opened Pandora’s Box. For the average gemmologist/appraiser, the scramble to remain a viable component of the industry may have just begun.

Historical perspective

[2]

[2]When General Electric first announced its successful synthesis of diamonds in 1955 and then gem-quality diamonds in 1971, some people proclaimed the end of the natural diamond industry; it remains to be seen if they were wrong or just half-a-century premature.

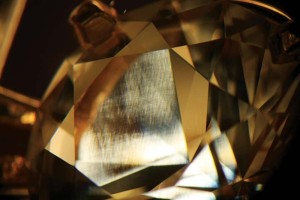

The large-scale production of gem-quality synthetic diamonds seems to have begun in earnest in 1985 with Sumitomo’s products that weren’t originally intended for the jewellery industry. In the case of the General Electric diamonds, the cost per carat of synthesis far exceeded the cost to extract comparable natural stones, so simple economics ended that ‘threat.’ The Sumitomo diamonds were primarily intended for the electronics industry and were fancy orangey-brown and brownish yellow in colour. Diamonds in those hues are a specialized market and they posed little economic challenge for the industry at large.

The next few decades saw ‘improvements’ in the quality and economic viability of gem-quality synthetic diamonds, but technological limitations continued to restrict their availability. For nearly 50 years, high pressure/high temperature (HPHT) techniques were the only methods used to produce synthetic diamond. The nature of the HPHT process makes small fancy colours much more economical to grow, and with the proliferation of the technology within the last decade, there has been a surge in the use of fancy-coloured melee diamonds by jewellery manufacturers. Coincidence? Everything changed in 2003 when Apollo Diamond, Inc., announced the successful growth of single-crystal diamonds using the chemical vapour deposition (CVD) process.

Although a relatively new process, CVD seems poised to knock down the technological and financial barriers that have kept synthetic diamonds mostly on the periphery of the jewellery industry. As the number of growers continues to increase, the last remaining hurdle may be broad-based customer acceptance of the product. De Beers Diamond Promotion Service spent countless millions of dollars marketing the emotional and intrinsic value of diamonds to consumers around the world. For the time being, synthetic diamond manufacturers seem to be reaching out to the socially conscious consumer. The persistent blood diamond issue, combined with growing awareness of the environmental damage caused by mining activities, seems to be resonating among that group of diamond buyers.

Lab-grown diamonds are, indeed, free of those stains. However, they have other ‘issues’ to deal with, and it’s important to remember that no manufactured product is free of environmental and social costs. ‘Value’ as an economic and perceptual concept related to diamonds and gemstones is based on the relationship between desirability and rarity. Synthetic stones can never claim to have economic value, since rarity is only related to manufacturing capacity; perhaps that explains the push to emphasize their ‘social’ versus ‘intrinsic’ value. They will have a ‘price,’ since there are many costs associated with their production and sale. Over the next several years, we’ll find out if diamond growers can reduce the price sufficiently to overcome the perceived lack of inherent value. In the meantime, individual gemmologists and appraisers are left with the challenge of simply trying to identify the product.

Clues for the clueless

[3]

[3]It’s important to remember that positive identification of a modern synthetic diamond will most often need to be done by a laboratory capable of performing and interpreting the results of specific tests. In general, that means those labs in possession of deep ultraviolet imaging equipment, along with an infrared spectroscope, and their appropriate databases. This equipment and the necessary training for its use are currently available for purchase. However, the cost per potential use makes the expense difficult to justify for most of us. Eventually, as synthetic diamonds make further inroads into the mainstream jewellery markets, we may discover that some version of this testing equipment becomes as necessary to our business model as a binocular microscope is today.

However, we shouldn’t be disheartened—even without having the ‘ultimate’ gadgets, we’re not yet completely helpless. Many of us already have the equipment necessary to perform basic tests that might separate a large percentage of diamonds. The idea is to try to find evidence that a diamond is NOT synthetic using our microscope, spectroscope, ultraviolet lamps, rare-earth magnet, and a variety of filters possibly combined with immersion. If we can’t determine that our client’s diamond isn’t synthetic, it probably needs to go to a major lab. The following tests are not likely to ‘prove’ a diamond is synthetic; we’re simply building evidence for a reasoned conclusion.

Microscope

[4]

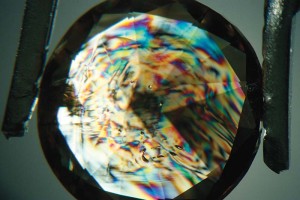

[4]Most of us have looked at many hundreds of diamonds under the microscope and probably don’t need much help recognizing inclusions. There are specific types of inclusions and inclusion assemblages that have never been found in a laboratory-grown diamond; therefore, if you find any of them, you’re not looking at a synthetic diamond. One of the easiest to recognize as a signpost is a colourless crystal. A garnet crystal is also an indicator of natural origin. On the other hand, black granular inclusions or feathers are not necessarily indicative of natural origin.

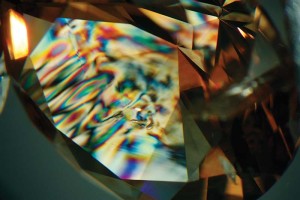

While you’ve got your microscope handy, pull out your polarizing filters and check for the presence and appearance of any ‘strain’ or anomalous double refraction (ADR). Virtually all natural and some synthetic diamonds indicate ADR to a certain extent when examined between crossed polarizers. It is a very good idea to become familiar with the patterns found in known natural diamonds, since these can be a strong indicator of origin. Technically, they’re actually an indicator of the forces at work when the diamond formed and can also be useful in determining the diamond type. A contributor to this magazine, Branko Deljanin, along with Dusan Simic, has developed a half-day class on using crossed polarizing filters to identify diamond types and synthetic diamonds. This is the sort of educational offering that is essential to help us hone the skills we’re going to need to remain a viable part of the industry.

Still using the microscope, another important growth characteristic to check when examining fancy-coloured diamonds is the grain pattern and the colour zoning. HPHT synthetic diamonds can sometimes show very specific boxy grain patterns and distinctive colour zoning. The use of a light-diffusing filter can sometimes make these subtle features easier to see.

Ultraviolet

[5]

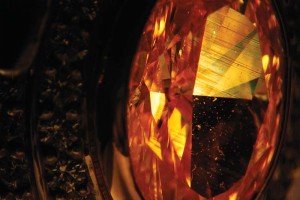

[5]One of the distinguishing characteristics of many synthetic diamonds is that when fluorescence is present, it will be stronger under shortwave UV. The odd greenish or orangey to orangey-red fluorescence might also raise an eyebrow, since those hue ranges are very rarely seen in natural diamonds. Conversely, pure blue fluorescence is relatively unusual for synthetic stones. Most CVD synthetic diamonds are Type IIa and, therefore, transparent to shortwave ultraviolet light. It would be relatively easy to check this, since we should already be testing any high-colour, high-clarity diamond that may have been HPHT treated for this property.

Spectroscope

If one is skilled and practiced enough to confidently and consistently locate the Cape absorption line at 415 nm, then it’s good to know its presence proves a diamond’s natural origin. On the other hand, colourless/near-colourless CVD diamonds typically have no visible absorption spectrum.

Magnet

[6]

[6]Very strong rare-earth magnets can be handy sometimes. In the case of HPHT synthetic diamonds, the presence of metallic inclusions may cause the diamond to be attracted to the magnet. Mounted stones can sometimes be ‘floated’ in a bowl of water using a piece of Styrofoam to help negate the effect of the jewellery’s mass. Be aware that some platinum alloys are also magnetic, so if the ring jumps onto the magnet, it’s probably not the diamond that’s reacting! As a side note, the magnet can also help identify some members of the garnet family.

Brave new world

We live in a time when the unscrupulous salt parcels of melee with synthetics and the longstanding traditions of honesty and trust within the diamond supply chain are breaking down as globalization becomes the norm. Consumer access to worldwide markets via the Internet and the relentless pursuit of bargain prices means many of us will be confronted with questions we may not be able to answer.

It’s important for those of us on the frontline to recognize when we’ve reached the limits of our equipment and abilities. As with life in general, gemmology and valuation involve a certain degree of uncertainty that we are forced to accept as simply part of the process. My advice, as always, is to disclose our limitations and provide our client advanced testing options to eliminate the guesswork. In the meantime, we should all do everything in our power to stay abreast of current developments in this rapidly changing industry.

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

[7]Mark T. Cartwright, ISA CAPP, ICGA, CSM-NAJA, GG (GIA) is president of The Gem Lab, I.C.G.A., an independent American Gem Society (AGS)-accredited gem laboratory. He has been a jewellery designer, goldsmith, gemmologist, and appraiser for more than a quarter century. Cartwright can be contacted via e-mail at gemlab@cox-internet.com[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Yellow-diamond-pendant-flat.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Type-IIa-micrograph.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Yellow-diamond-grain.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/brown-diamond-not-IIa.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ADR-with-crystal-inclusions.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Type-IIa-diam-pendant.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Mark-Cartwright.jpg

- gemlab@cox-internet.com: mailto:gemlab@cox-internet.com

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/something-seems-amiss-synthetic-diamonds-amongst-us/