Subjectively speaking: How a single word changes everything and nothing

by charlene_voisin | May 1, 2015 9:00 am

By Hemdeep Patel

[1]

[1]

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”¦” Famously penned by Charles Dickens in A Tale of Two Cities, those words might seem an appropriate mindset as we make our way through 2015. It would seem consumers are now aware of the jewellery industry’s dirty little secret: diamond grading is subjective. Though many graded stones are generally accepted as accurate to the issued report, there are just as many reports containing grading errors or bias. Sometimes the grades are overstated and in the rare case, they are downright fraudulent. The events over the last year are providing us an opportunity to take a deep breath and decide which direction we, as contributing individuals to our industry, want to take our business.

That’s just its nature

[2]

[2]Last summer, three consumers sued a jewellery retailer in Tennessee, each claiming EGL International reports they had received for diamond jewellery they purchased overstated the stones’ clarity and colour grades. Though the three lawsuits were settled out of court, the story doesn’t end there. With the publicity and online chatter that erupted regarding the lawsuit, Martin Rapaport delisted all EGL-graded diamonds a few months later from his diamond trading platform, RapNet.

Now I do need to clarify that EGL International and EGL USA, the latter of which has been active in Canada for the last 12 years, have no business affiliation and only share the acronym, EGL. Although the industry is generally aware of this distinction, Rapaport felt consumers would not know the difference—EGL is EGL is EGL. Polygon, another diamond trading platform, disagreed with Rapaport, choosing to delist only EGL International-graded diamonds.

In December 2014, the trade publication, National Jeweler, reported a class-action lawsuit against EGL International and unnamed major retailers was in the works, charging the “lab systematically over-graded diamonds the retailers then knowingly sold to consumers.” (As of this article’s writing, no lawsuit had yet to be filed.)

My first thought when I heard the news was why did it take so long for a retailer to be taken to court over the issue of an over-graded diamond? After all, over-grading had been the topic of conversation in diamond circles for many years.

I can say quite confidently that many, if not every member of the jewellery industry, is aware that grading diamonds is a subjective endeavour. However, this vital piece of information is not always what a consumer is told. Rather, grading terms are presented as absolutes and unwavering. When called out on what appears to be conflicting grades for the same stone, the answer usually given a consumer is that grading diamonds is subjective and that even graders at the same lab routinely come up with different grades. That’s just the nature of grading diamonds, they say.

[3]

[3]However, there are less scrupulous scenarios at play sometimes. In cases where the jeweller is responsible for providing a corroborating grading report, he or she usually finds an appraiser to confirm the findings of the first lab. At the same time, the consumer may decide to find their own appraiser to re-grade the stone. So far, nothing in this situation is questionable. When the grades are off beyond reason, there have been cases where a dishonest jeweller tries to cast a shadow on the appraiser’s capabilities or experience; to soothe any suspicion, he or she presents enough documents to corroborate the ‘better’ report. I’m sorry to say we have had jewellers approach our lab to engage in this type of activity. Suffice to say, we declined.

I’m no lawyer, but anyone who has been following the EGL story can safely surmise this lab’s defence will surely be that the entire grading system is subjective and there are no absolutes. So we are left with the question of how to deal with the subjective nature of grading diamonds. The fact is, there are no universally accepted standards, and let me explain what I mean by that.

Grading to GIA or AGS standards is universally accepted and implemented by labs around the world; reports from these two laboratories, especially GIA’s, have a massive captured market among jewellery retailers and consumers. It is also true the discounts and margins for diamonds traded on these reports are very tight. Other labs looking to run a profitable business have to provide some sort of value proposition as to why a diamond would simply not be sent to GIA or AGS to be graded. Further, the idea of grading standards is not comparable to those found and used in the scientific and engineering industries, where measurable quantities are overseen by a governing body. This is a whole other topic of discussion that we’ll put aside for now.

Regardless of EGL International’s legal difficulties, the natural question to ask is, where do we go from here? If the courts make it impossible for EGL International to exist as a business, does this address the issue of overstated grading reports by others and the lack of standardization? Unfortunately, I would say no.

Standardizing subjectivity

[4]

[4]The lack of standardization is the underlying issue to the grading dilemma, and subjectiveness is the result. That said, I am unable to see a solution that would bring standardization to grading policies and procedures. I say this because although GIA established the grading terminology most labs use, the actual scale used to differentiate grades varies amongst labs. Each institution has a market it caters to, clients that have grown accustomed to its grading scale, and subjectiveness that allows a certain profit margin. As these labs carve out their niche in the marketplace, they may become more and more unwilling to give up their grading methodologies and practices to a governing body for fear they will lose market share. Standardizing a subjective endeavour doesn’t sound so easy, does it?

In addition, as laboratories grow bigger and gain a broader reach by opening grading facilities in more places, there is a natural decline in standards. No matter how subjective, gemmological standards are maintained by setting up systems and procedures that self-monitor grading protocols and results. As laboratories open new grading facilities, they work to gain traction as quickly as possible in their new market. And although systems are put in place for business procedures, setting up monitoring systems to track grading accuracy is difficult to do while bringing new diamond graders up to speed on the lab’s standards. It’s a matter of how do you divide your attention and resources. In effect, the subjectiveness of grading becomes more apparent as you compare the standards at the parent laboratory to its extensions. It’s not unusual for members of the diamond trade to prefer getting diamond reports from the parent laboratory, rather than their extension.

What do we do now?

[5]

[5]Although I have painted a bleak picture, I would suggest there is a great opportunity for brick-and-mortar retailers to stand out. While e-tailers offer stones and their gemmological reports as absolutes, the subjective nature of diamond grading provides jewellery stores a chance to show prospective customers this is not the case.

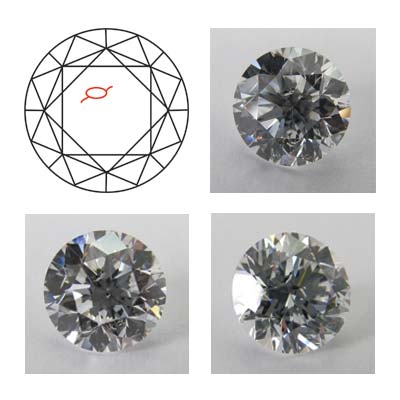

More importantly, though grading standards are subjective, there is a wide range of possibilities along scales, and it’s in those opportunities that real value can be found. In short, stones should be bought and sold based on what they are, rather than what grading reports indicate. What do I mean by this? Well, a buyer should be fairly comfortable in determining a stone’s grade is accurate to the diamond report presented. Over the years, we’ve found the opportunity for a real value purchase should be in trying to find stones at the higher end of a diamond’s reported grade. For example, when buying an SI1 stone, a buyer should look for a diamond that would rank it closer to a VS2, rather than an SI2. I believe jewellery retailers will need to become very good at finding these opportunities—specializing in a particular range of diamond grades is the first place to start. By that I mean they will need to learn how to accurately grade stones in this range and know what inclusions to look for that make the stone a good buy.

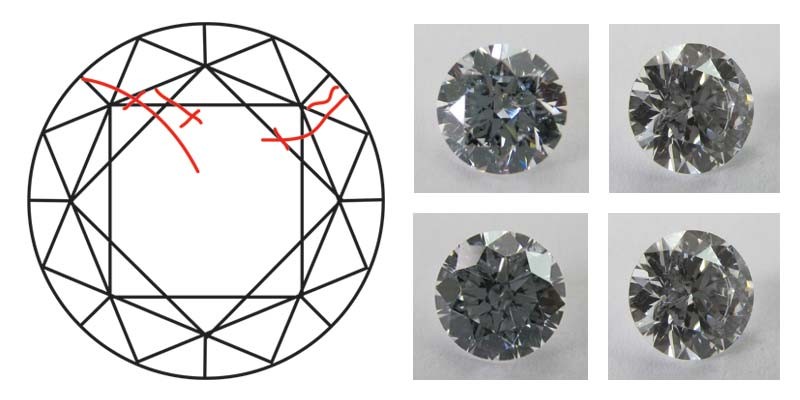

For instance, my brother, Kamal, and I have found that an SI2 with twinning wisps, rather than a centre inclusion, is a good buy in some unique situations, since to receive this grade the inclusion needs to be quite large or very obvious (i.e. noticeable under 10x magnification, although in many instances, it can also be partially visible to the naked eye). Alternatively, a twinning wisp in an SI2 is noticeable as a cobweb under 10x magnification, but cannot be seen when viewed with the naked eye.

As has been a theme in all of my previous articles, opportunities in buying can only be found when you actually observe and examine the stone you purchase. And so in keeping with that, I would like to share an interesting fact brick-and-mortar retailers can use the next time they find themselves competing with online retailers. Trying to interpret a gemmological report is a tough task at the best of times, but trying to make sense of the digital plot can be a nightmare. Now taking the twinning wisp example in the previous paragraph, logic and intuition may tell you a diamond plot with the minimal of information or marking is the best. While the diamond plot of the twinning-wisp stone makes the diamond undesirable on paper, it is through observation that the subjectiveness of the grades will be noticeable.

I spent my undergraduate years in university studying physics and astronomy, two subjects where we dealt with absolutes. What I came to realize is that a question with many possible answers doesn’t sit very well with me, which is why I have never felt comfortable with the subjective nature of diamond grading. Over the years, I have found that being able to sell beyond the grading report is one way to help the jewellery industry succeed. While some may disagree with my position, I’ve also come to appreciate that in not talking openly about the issues, as was the case with over-graded diamonds, no progress toward a solution can be made.

[6]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and vice-president of the Ontario chapter of the GIA alumni association. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at hemdeep@hkdlab.ca[7] or sales@creativecadworks.ca[8].

[6]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and vice-president of the Ontario chapter of the GIA alumni association. Patel can be contacted via e-mail at hemdeep@hkdlab.ca[7] or sales@creativecadworks.ca[8].

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/bigstock-Vector-illustration-of-a-reali-25555529.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/included-crystal.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Twinning-wisp.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/bigstock-Man-choosing-engagement-ring-a-62111405.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/bigstock-precious-stones-and-equipment-9243572.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Hemdeep-Patel.jpg

- hemdeep@hkdlab.ca: mailto:hemdeep@hkdlab.ca

- sales@creativecadworks.ca: mailto:sales@creativecadworks.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/subjectively-speaking-how-a-single-word-changes-everything-and-nothing/