Survival of the fittest: Adapting to evolving technologies

by jacquie_dealmeida | December 1, 2015 9:00 am

By Hemdeep Patel

[1]It could be said the evolution of technology is a form of business Darwinism—that as technological innovations are introduced, long-established industry norms disappear. All through the evolution of human society, growth and advances in technology have served as a way of improving, replacing, or creating new purposes, as well as fostering ideas and development. Throughout the ages, machinery and manufacturing tools have replaced the human hand—the ideology of the old became redundant and inefficient.

[1]It could be said the evolution of technology is a form of business Darwinism—that as technological innovations are introduced, long-established industry norms disappear. All through the evolution of human society, growth and advances in technology have served as a way of improving, replacing, or creating new purposes, as well as fostering ideas and development. Throughout the ages, machinery and manufacturing tools have replaced the human hand—the ideology of the old became redundant and inefficient.

In some cases, individuals or companies caught in the middle of the tool or skill being replaced were often best-suited for the change and found success in ushering the new age. These were the businesses that found blending the advantages of the tools of old and the technology of new allowed them to be versatile, grow very quickly, and work efficiently.

The growth and application of CAD/CAM technology in the jewellery industry is quite unique and worth examining, given the way it has fundamentally transformed how business is done today. The technology has impacted everything from jewellery manufacturing to the purchase process at the retail level. But more importantly, the jewellery industry may be seen by those on the outside as one that has successfully combined hundreds of years of manufacturing processes with cutting-edge technologies. Indeed, CAD/CAM technology has morphed from a primarily business-to-business (B2B) model to business-to-consumer (B2C).

Out of sight, but never out of mind

As with any emerging technology, the first inclination is to examine how and what the new tool replaces. For the jewellery industry, CAD/CAM was seen as the evolution to crafting models by hand. For these artists, their canvas was a block of wax or wires of metal, their tools of the trade anything from a surgical knife and wax pen to a gas torch. These artists could create anything and everything, from one-of-a-kind statement pieces to the master model used for large-scale manufacturing. To get a full sense of the scope and breadth of how skilful these artists were, just take a quick look back to the years prior to the 1980s. Consider anything from the crown jewels to pieces from exclusive iconic houses, such as Cartier, Tiffany, and Bulgari to large-scale jewellery manufacturers that supplied the vast majority of traditional brick-and-mortar stores.

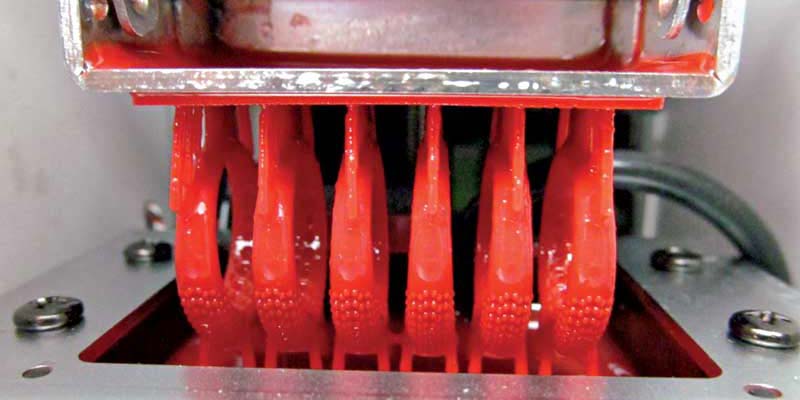

Fast forward to 2015 and it could easily be said the vast majority of jewellery manufactured today is built on a computer screen and with the aid of 3-D printers. The benefits are obvious for this new way of manufacturing: the speed at which models or even entire jewellery lines are manufactured can lead to dramatic cost savings. In addition, a wider range of design options can be built with the help of CAD, featuring elements that may not be feasible through traditional hand fabrication. But this rule is by far not universal. There are many instances where hand fabrication makes more sense because the finish is better or it is the less expensive option. This is where the ability to straddle the technologies of the old and new becomes very important, as is identifying which tool to use to take the final result from simply average to exceptional.

Engraved jewellery and creating a fitted wedding band for a pre-existing engagement ring are two tasks we look to skilled artists to complete. For fitted bands, we may consider a few points to decide whether CAD or hand fabrication is best suited for the job. First, did you design the initial engagement ring? Is the inside edge where the engagement ring and the wedding band meet a straight line? Will the piece incorporate stones? How are they set and does their layout on the engagement ring and wedding band need to match? Do the left and right sides of the ring mirror one another? What is the time frame for the job? Even though we may have to balance considerations when choosing one method of construction over the other, we can certainly derive a very good idea of what will give us the best result.

Another element some may argue that has not yet been successfully duplicated by CAD/CAM technology is the sharpness of hand engraving. The true limitations of 3-D technology may be apparent once the model has been printed and cast. For example, our experience has been that extremely fine detail may not survive the printing process. In those cases where it does, the fine detail may be lost during casting, cleaning, and polishing. On the flip side, engraving applied by hand onto metal leaves a clean, sharp edge.

On the flip side

To see what may be coming around the bend, let’s take a closer look at today’s developing technologies. For geeks like my brother and me, it is the development of innovative applications and purpose that intrigue us, which is one of the reasons we expanded our business to included CAD/CAM services. And in the case of the jewellery industry, the primary focus of new applications is moving the business into the digital sphere, where information can be delivered by e-mail or presented to a wide audience through the Internet. In other words, the effective use of a limited resource that gains the largest viewing audience.

We have seen this idea applied in the diamond industry, where gemmological reports have turned live inventory into digital commodities that can be e-mailed anywhere in the world to secure a sale without the buyer ever examining the stone. In the case of CAD/CAM technology, the digital 3-D scanner is a new addition to the technology landscape, allowing users to take live products and convert them into digital objects that can be distributed, modified, and delivered electronically.

The technology is simple, but its application is quite broad. The scanner comprises software controlling a digital camera that orientates itself 360 degrees around an object to capture a complete set of images. The images are then stitched together into a 3-D view of the object that can be further modified using a wide range of software. These devices are available at various price points and are suitable for numerous applications. For instance, a hobbyist may take a 3-D scan of an object with the use of a tablet and have it printed. Those who are skilled in CAD software may modify the scan by building an attachment or addition onto it. A quick look at Shapeways—an online 3-D printing service—gives you a sense of the possibilities. (You may find the section under ‘gadgets’ particularly interesting.)

Digital scanners suitable for jewellery applications—which are quite varied and unique—are much more expensive due to the finer level of details required. And so if a matching wedding band is needed for an engagement ring, a scanned 3-D model can provide the designer with an excellent starting point for building the matching piece. Or if a customer has lost an earring, a replacement can now be a scan away. Another use for 3-D scanners is to digitally recreate a gemstone to be incorporated into a CAD design. This is often a good solution when the stone has a unique cut or its pavilion is difficult to measure due to an off-centre culet. It may also be an appropriate tool when the stone is particularly expensive and the seller is unwilling to part with it until the sale is complete. By creating a 3-D image of a stone, it is possible for a CAD designer to build a piece of jewellery without ever seeing or touching it.

A unique opportunity

After exploring the wider application of 3-D printers over the last year, my brother and I came to understand the jewellery industry is quite unique compared to others in that technology has gone from being solely in the hands of manufacturers and designers to that of the retailer. Many jewellery stores are showcasing the use of CAD/CAM technology as an integral part of their business—I have several customers who present my digital renderings and designs as part of their custom jewellery service. And many are finding that with 3-D printers becoming more affordable, it is now easier to migrate into CAD/CAM. This cannot be said of most other retail industries, as the manufacturing processes are still well behind the scenes.

Jewellery retailers have a unique opportunity to showcase how their business has combined traditional manufacturing methods and cutting-edge technologies. At the moment, I know there is a better-than-average chance many consumers have not seen how CAD/CAM technology works, and so today’s jewellers have a unique opportunity to engage with their clients in a more meaningful way and showcase the old and new artistry of jewellery making.

[2]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3-D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and vice-president of the Ontario chapter of the GIA alumni association. He can be contacted via e-mail at hemdeep@hkdlab.ca[3] or sales@creativecadworks.ca.[4] Â

[2]Hemdeep Patel is head of marketing and product development of Toronto-based HKD Diamond Laboratories Canada, an advanced gemstone and diamond laboratory with locations in Bangkok, Thailand, and Mumbai, India. He also leads Creative CADworks, a 3-D CAD jewellery design and production firm. Holding a B.Sc. in physics and astronomy, Patel is a third-generation member of the jewellery industry, a graduate gemmologist, and vice-president of the Ontario chapter of the GIA alumni association. He can be contacted via e-mail at hemdeep@hkdlab.ca[3] or sales@creativecadworks.ca.[4] Â

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CAD-main.jpg

- [Image]: http://www.jewellerybusiness.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Hemdeep-Patel-e1448553068667.jpg

- hemdeep@hkdlab.ca: mailto:hemdeep@hkdlab.ca

- sales@creativecadworks.ca.: mailto:sales@creativecadworks.ca

Source URL: https://www.jewellerybusiness.com/features/survival-of-the-fittest/