Greenhouse gas emissions

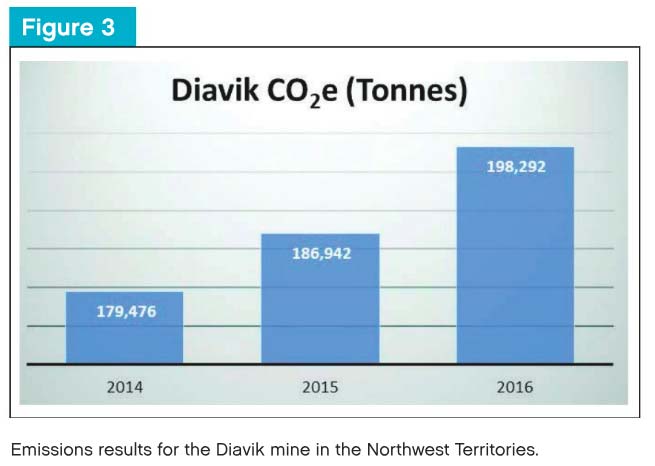

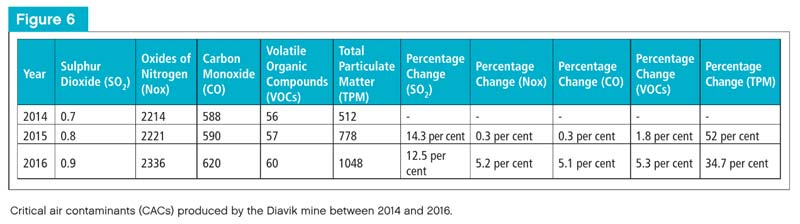

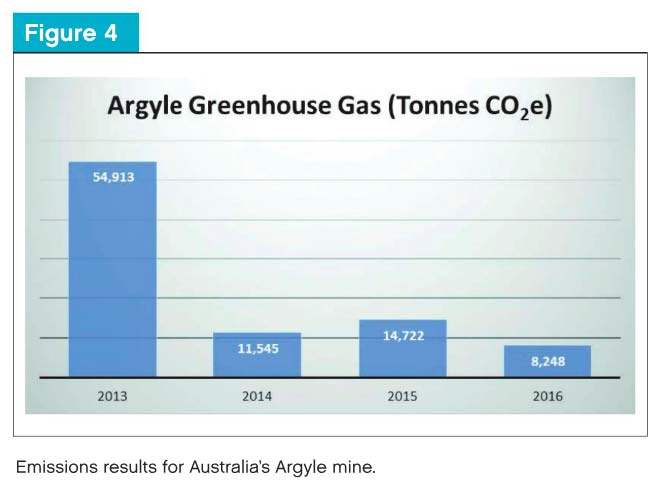

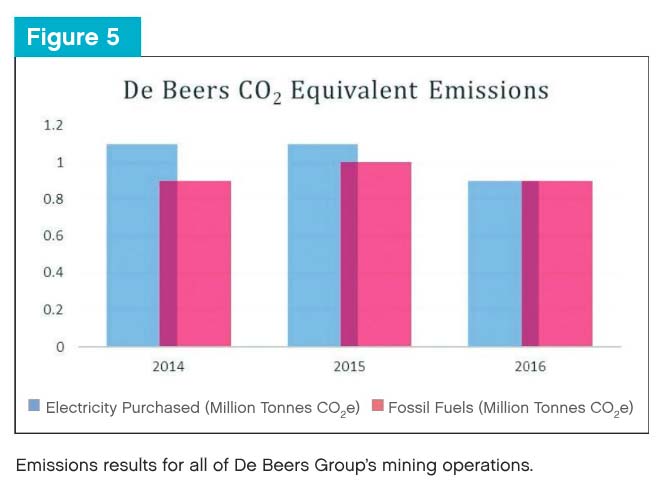

It is obvious diamond mining companies fall short in the emissions category. Figures 3, 4, and 5 show the emissions results of the Diavik mine, the Argyle mine, and De Beers Group’s operations. Between 2015 and 2016, Diavik’s emissions grew by 6.07 per cent whereas Argyle’s decreased by 44 per cent. De Beers stayed relatively steady, but it also has a larger portfolio of mines. Further, over the past three years, the Diavik mine has increased its critical air contaminants (CACs), which affect air quality, plants, and both human and animal respiratory systems (Figure 6).

In 2017, De Beers announced Project Minera, an effort to become carbon-neutral by storing large volumes of carbon in kimberlite tailings (the residual material left after diamonds have been extracted). This is a natural process, as kimberlite has properties for storing carbon. The risks and uncertainties have yet to be ironed out, but as Bruce Cleaver, CEO of De Beers, aptly puts it, “This project could play a major role in changing the way not only the diamond industry, but also the broader mining industry addresses the challenge of reducing its carbon footprint.”

Although lab-grown diamond producers do not share their GHG emissions, it is highly unlikely they are contributing the same amount as diamond mining companies, as the latter need fuel for transportation, operating large machines, and running large facilities. Currently, the Diamond Foundry is the only lab-grown diamond producer certified as fully carbon neutral.

Unfortunately, without sufficient evidence, it is very difficult to establish an accurate carbon footprint. Further, lab-grown producers are not disclosing which metal alloys they utilize to make their diamonds. Many also do not mention the fact CVD diamonds need a seed diamond (natural or lab-grown) in order to be grown. (Click here to read R. Linares’ piece, “CVD-grown Synthetic Diamonds, Part 1.”) These mined metal alloys and extra diamonds should be factored into the assessment.

Unfortunately, without sufficient evidence, it is very difficult to establish an accurate carbon footprint. Further, lab-grown producers are not disclosing which metal alloys they utilize to make their diamonds. Many also do not mention the fact CVD diamonds need a seed diamond (natural or lab-grown) in order to be grown. (Click here to read R. Linares’ piece, “CVD-grown Synthetic Diamonds, Part 1.”) These mined metal alloys and extra diamonds should be factored into the assessment.

Water use

Water is one of the most precious resources for diamond miners. It is important not only for the health of mine workers, but also for processing. (This information comes from the diamond mining section of GIA’s ‘Diamonds & Diamond Grading’ course.)

In 2016, South Africa experienced a severe drought, requiring De Beers—which operates several mines in that country—to focus on water reduction. The company’s subsidiary Element Six launched Diamox, a system that treats highly contaminated industrial wastewater by using lab-grown industrial diamonds to remove dissolved pollutants. (For more, For more, see De Beers Group’s Socio-economic Impact Report, produced by Ernst & Young in 2016.) The process is electrochemical, making it highly effective and sustainable. It is even safe to put the water back into the environment after treatment. In De Beers’ 2016 Report to Society, the company outlined its reduction in water use over the past three years (Figure 7).

Another major water-related issue stemming from diamond mining is dewatering of Canadian lakes. In the Northwest Territories, many kimberlite pipes are found at the bottom of lakes. Diamond miners operating in Canada must take special precautions in conserving fish and other species, as well as monitoring biodiversity where they mine.

Both CVD and HPHT lab-grown diamond producers use freshwater in their processes. In an interview with this author, Dean VandenBiesen, vice-president of LifeGem, said water circulates in his company’s chiller systems to keep the machines from overheating. VandenBiesen described this as a closed system that does not allow measurement of the water used. Similarly, a representative of the Diamond Foundry indicated the company uses 7.5 to 113 L (2 to 30 gal) of freshwater per carat, which is approximately one shower’s worth per carat. Overall, gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers consume considerably less water than mining companies.

Both CVD and HPHT lab-grown diamond producers use freshwater in their processes. In an interview with this author, Dean VandenBiesen, vice-president of LifeGem, said water circulates in his company’s chiller systems to keep the machines from overheating. VandenBiesen described this as a closed system that does not allow measurement of the water used. Similarly, a representative of the Diamond Foundry indicated the company uses 7.5 to 113 L (2 to 30 gal) of freshwater per carat, which is approximately one shower’s worth per carat. Overall, gem-quality lab-grown diamond producers consume considerably less water than mining companies.

Land conservation and biodiversity

There is no question ‘team lab-grown’ wins the land conservation and biodiversity category. All forms of mining leave an environmental footprint, which sometimes cannot be remediated. However, it is worth mentioning mining companies’ efforts to restore the land and ecosystems they affect.

In Canada, many mining companies are required to work with third-party environmental groups to assess their impact on the ecosystem. For instance, Diavik has the Environmental Monitoring Advisory Board (EMAB) to monitor specific biodiversity concerns, such as water and air quality and impact on fish, mammals, and birds.

De Beers’ Victor mine is undergoing a progressive reclamation process that began in 2014. Last year, De Beers spent $4.2 million on land conservation at Victor, and this year it plans to also spend another $7.2 million. The process involves planting 477,110 trees of different varieties, all of which are native to northern Ontario’s ecosystem.